Mapping: An Exercise in Cartography

Ally Bisshop reports on conversations of the Mapping Slow Media group, where Artur van Balen, Yesenia Thibault-Picazo, Walmeri Kellen Ribeiro and Alexandra Toland participated in.

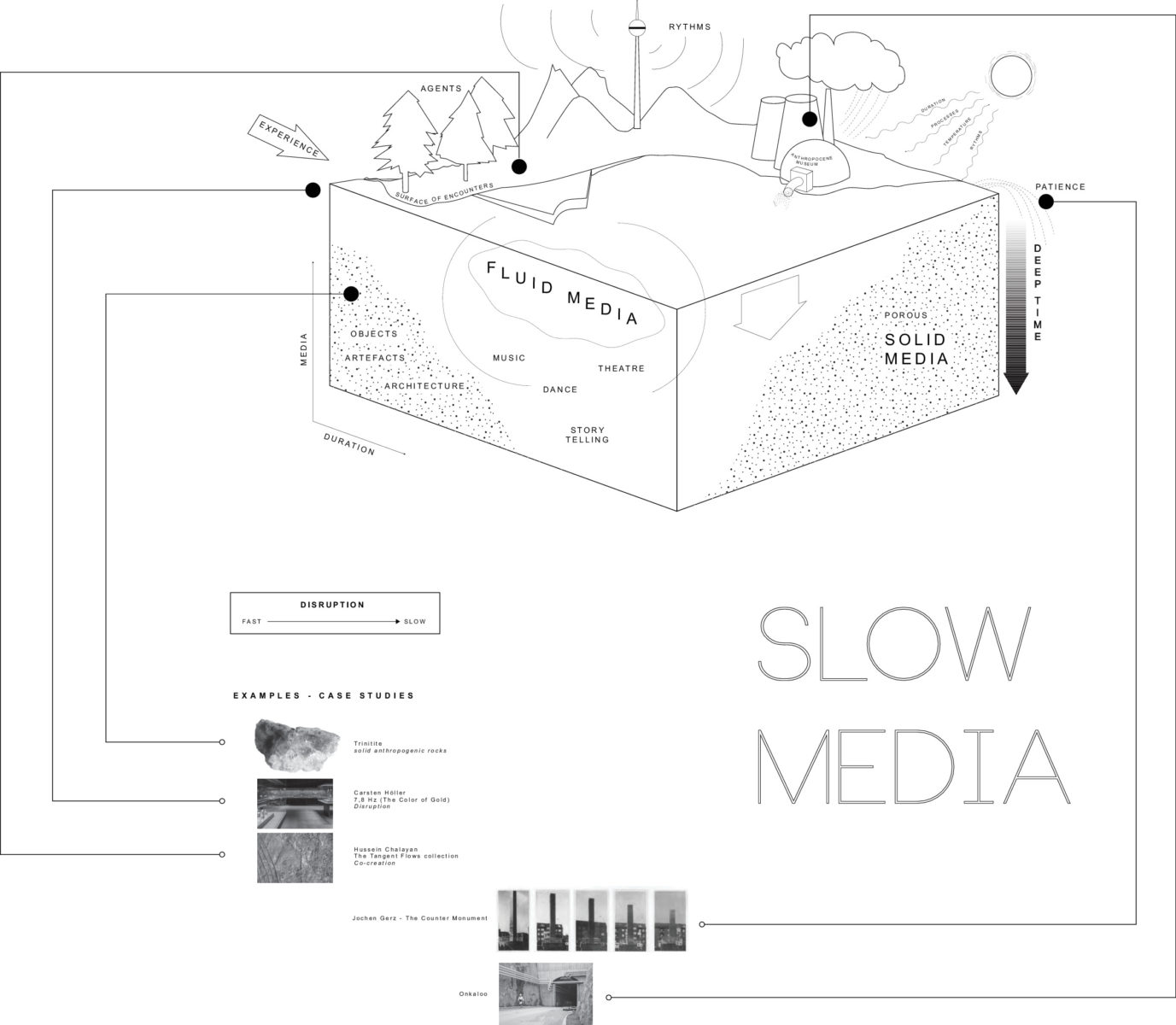

Diagram by the Slow Media Mapping group

As a cartographic exercise, “Mapping Slow Media” was not intended to complete and close the circuit of possibilities for inclusion under the umbrella of Slow Media. Rather, the intention was to generate an expanded conceptual framework for thinking about how such a map might be figured, and what its terms, nodes, and ground might be. We use the idea of the map Gregory Bateson explores in Steps to an Ecology of Mind:

Let us go back to the map and the territory and ask: ‘What is it in the territory that gets onto the map?’ We know the territory does not get onto the map. […]. What gets onto the map, in fact, is difference, be it a difference in altitude, a difference in vegetation, a difference in population structure, difference in surface, or whatever. Differences are the things that get onto a map.1

It is the difference that matters. What we began sketching is a map of difference, both actualized and virtual or potential. A map of the ways in which to think Slow Media is to think differently. The “Slow Media” mapping exercise began with an analysis of its two constituent terms:

What is slow?

What is media?

The slowness of Slow Media can be read in a number of ways. In one reading, it suggests something of a slowing down to the space and rhythm of an attentive encounter. Here, slowness speaks to a deceleration of one’s subjective sense of time, in order that we might open up to the possibilities provided by a contemplative engagement with ideas and theory. It also references the slowness that is required to digest and process the complex information and ideas communicated through these media, and the length of time that might be needed for a novel understanding to fully emerge from the ideas and questions that they pose. Additionally, slowness might speak to an ability of Slow Media to express or communicate expanded timescales: epochs and durations that exceed the human time frame, and that might encompass distal pasts and distant speculative or possible futures.

What constitutes a medium in the framework of Slow Media is a key constituent of this mapping project. There exist a multitude of organic and inorganic matter, objects, symbols, processes, movements, rhythms, and spaces that can be read as media—that is, as being inscribed (or inscribable) with information, ideas, or stories. These “other” media forms are those that exceed purely textual or figural media, that exceed mathematically or scientifically encoded forms, and that are not necessarily predicated on linear and visual narratives. Examples discussed included rocks—both Neolithic and specifically Anthropocenic (e.g. Trinitite, a rock formed as a result of plutonium testing at the Trinity test site in New Mexico); soil and its many nutrient flows and dynamic feedback loops; architectural spaces (museological or otherwise); food systems; birdsong; sunlight; dance and performance; and spaces that provoke an entrainment of embodied rhythms. Here, the examples of “other” media generated in this exercise are in no way intended to represent an “absolute diagram” of possible media forms, but to speak to the heterogeneity and complexity of the map itself.

In the context of mapping a Slow Media of the Anthropocene, the language of the medium must also be expanded to include (perhaps even foreground) movements and processes as legitimate sites of media production, reception, and communication. In cartographic terms, this translates to a heightened attention to the arrows or lines (indicating movements or processual linkages) between objects on a map, rather than the objects themselves. Here, the objects might exist not as endpoints within the map, or as canonical descriptors of absolute media modes, but as spaces of contextual pause, which always lead us on to a multitude of other possible movements, transformations, and ideas. Importantly, different media forms also embed or express different ways of knowing or different ontological frameworks, as well as different languages or symbolic or semiotic indices. Further, they call for different modes of engagement and attention, in order that we might perceive or read them as “media,” and therein grasp something of what is being communicated.

The expansion of the term media is important in trying to imagine a Slow Media that might have some agency in framing or reframing our collective approach to thinking the Anthropocene. Here, the expansion of media—to include the extratextual, the nonhierarchical, the nonlinear—might be that which opens us up to alternative ontologies, so that we might be able to thicken or recalibrate our approach to thinking through the suite of issues and questions posed by the Anthropocene. Donna Haraway has suggested: “it matters to destabilize worlds of thinking with other worlds of thinking.”2 Here is an imperative to reconstitute the language or media that frames our “worlds of thinking,” through an attempt to read the different forms of information given in an expanded realm of Slow Media. Haraway emphasizes the importance of “destabilization,” which is required first in order to open onto other frameworks of reading, listening, thinking, and knowing. Within a new conception of Slow Media, and its request for an expansion of “legible” media forms, there is an implicit and necessary disruption and dissociation from normative modes of thinking and knowing. The disruptive is then a key agent in the idea of Slow Media—the shift required from habitual conceptions of media and from habitual modes of attending to them, the shift required to disengage from accelerative temporalities and modes of cognition.