Nuclear Anthropocene

The phrase “atomic age” has been around since 1945 in reference to the world’s reframing by the newfound human control over nuclear forces. Nuclear weapons prompted both apocalyptic visions of humanity’s annihilation through mutually assured destruction and promises of abundance, progress, and modernity through the utilization of atomic energy. Since the first nuclear test detonation called “Trinity” and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, all in 1945, nuclear technology has profoundly changed the world’s history and geopolitics, as well as our daily life and natural world.

On the one side, the atrocities of mass destruction in Japanese cities, on Pacific Atolls, and other “testing sites” across the globe forever stamped the self-image of the human as an engineer of death. On the other side, harnessing nuclear power and the emerging nuclear sector were hailed as instruments of national security, a hotbed of technological innovation, a wellspring for electric household energy, and a radically modern means of investigating the natural world and improving human bodies and diets. But soon the smiling side of this Janus face faded, and threat of radioactivity became the scare phenomenon of the second half of the twentieth-century. Radioactive contamination has changed the natural and the social environment to an extent that brings a whole new register into focus: the possibility that life on this planet could end as we know it.

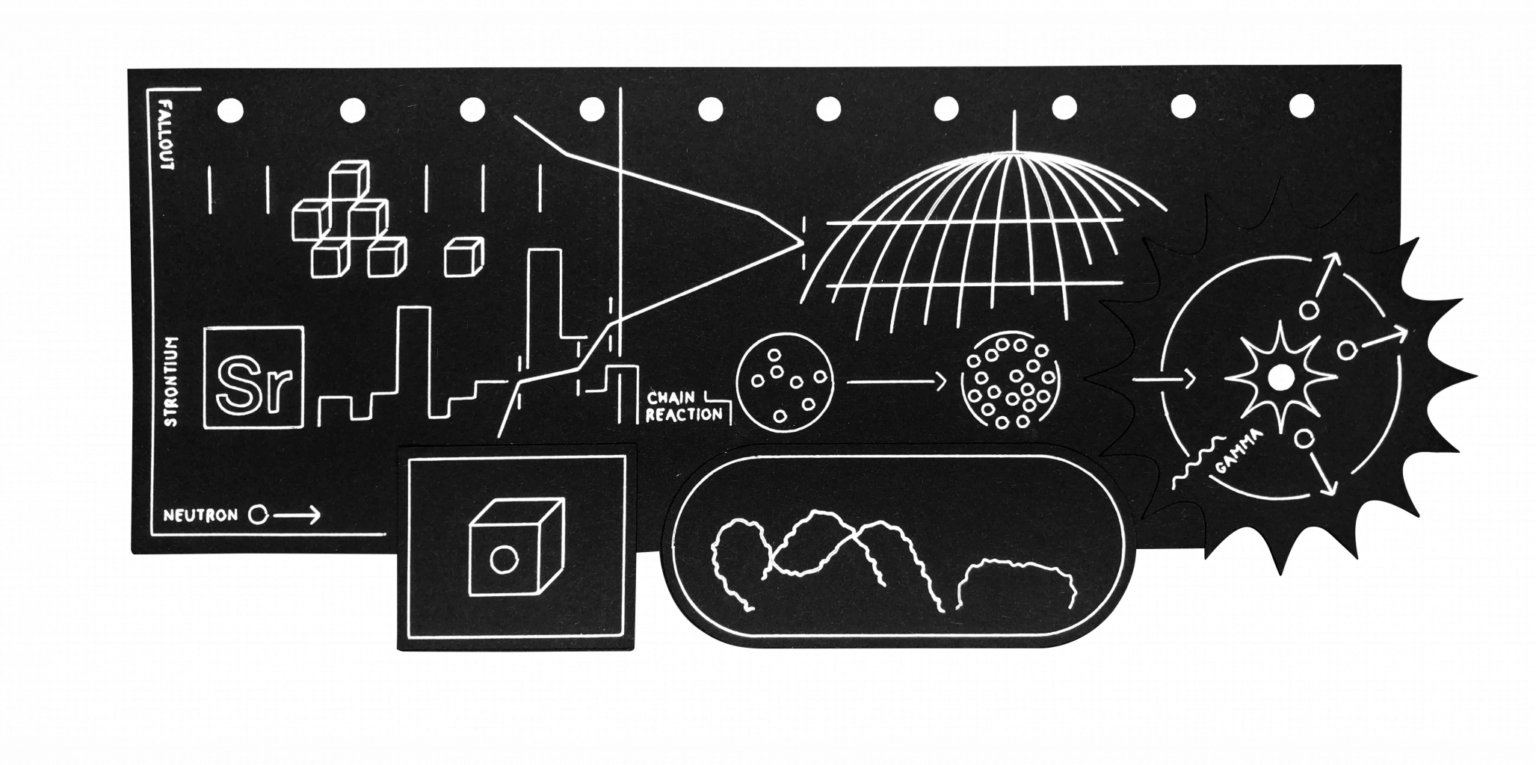

In the 1950s, radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons tests was the first phenomenon to be defined as a planetary environmental issue, and today, radioactive traces are quintessential indicators of humanity’s impact on the Earth. The dispersal of artificial radionuclides from atmospheric detonations that started in 1945 and peaked in 1961–1962 has emerged as one of the best candidate signatures to fulfil the required criteria for a marker of the Anthropocene: It is synthetic, globally synchronous, and enduring on a geological timescale. A suite of different radioisotopes (including strontium-90, americium-241, carbon-14, plutonium-238, -239, -240, and caesium-137), some rather short-lived and others with half-lives long enough to be detected more than 100,000 years from now, provide a chemostratigraphic signal for the onset of the Anthropocene.

Beyond the potential of geological periodization acquired by radiogenic tracers, the dossier explores the broader connection between the nuclear and the Anthropocene, paying specific attention to how nuclear technology has forged this world. How was the risk of radioactive contamination addressed, institutionalized, and managed? How has the global order that emerged with and has characterized the nuclear age served as a matrix for framing, understanding, and addressing Anthropocene challenges? With questions like these the dossier addresses the nuclear age as an epistemic and technoscientific setting from which a global way of thinking about the ecological crisis has emerged—not least through the role that small-scale and localized science has played in contesting consensus within that setting. Ultimately, nuclear technology has served as a primary model for the establishment of global monitoring networks and international regulation and governance frameworks, the very infrastructures which have made the Anthropocene thinkable and measurable.