Novel Materials and Technofossils

While some 5,300 natural minerals have evolved on Earth over geological time, they have been augmented by more than 200,000 different types of synthetic mineral-like compounds today. Some, like concrete, create the visible structures all around us. Others, like microplastics or synthetic aerosols, are volatile particles that we ingest and inhale without even perceiving. Whether visible or invisible to the eye, “novel materials” refer to the diversity of anthropogenic compounds that derive mostly from industrial production or industrial pollution and waste. Constituting our urban and also rural infrastructures, creating the material basis for modern daily life, getting dispersed through waste disposal and incineration: Novel materials make up the fabric of the technosphere.

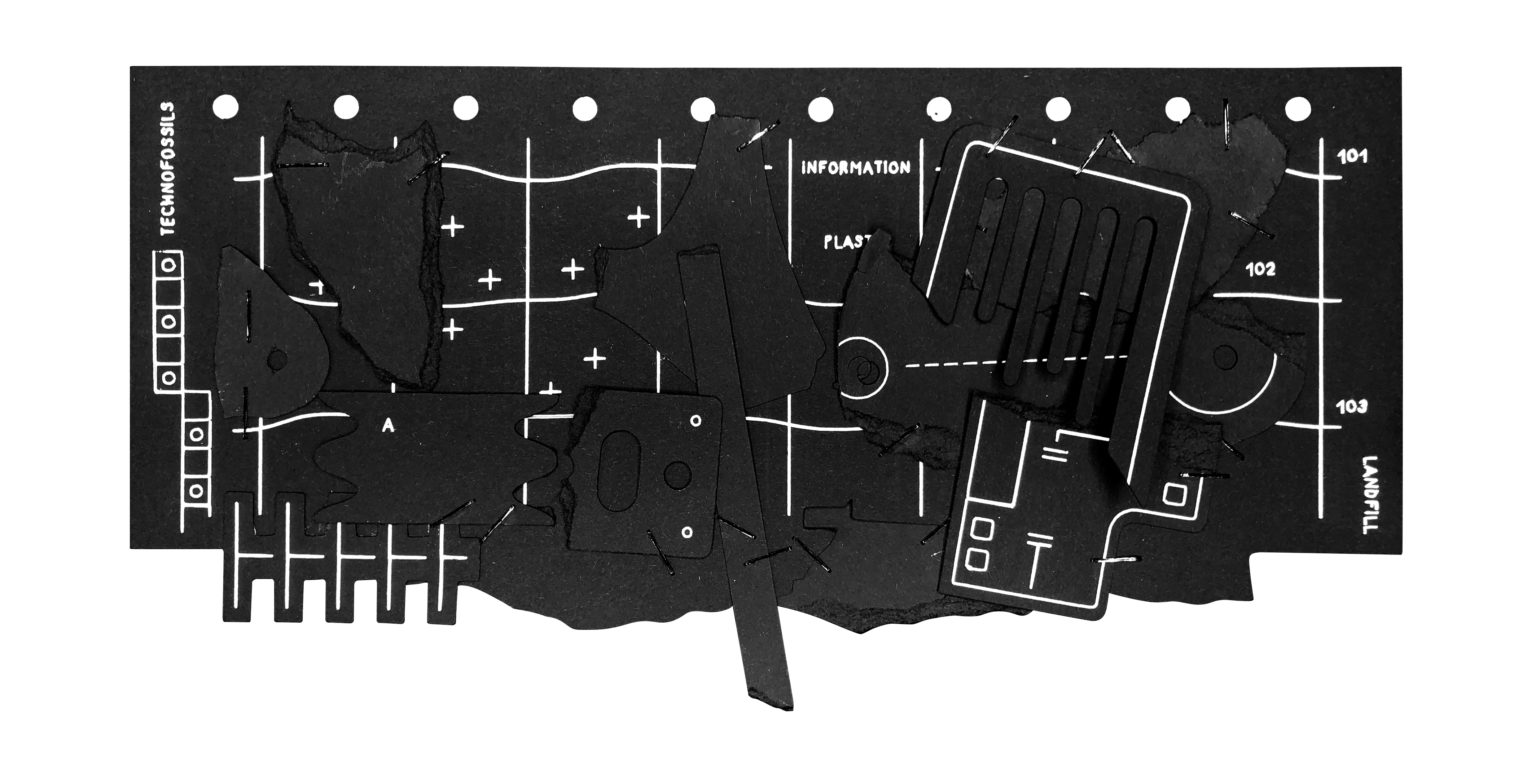

Synthetic materials are nothing new. Ceramic and bricks have been around for millennia and make up a substantial part of what is now labelled as “artificial ground” in stratigraphic parlance, echoing the terms of archaeological investigation. What makes materials “novel” is that they often represent elements that are rare or entirely absent in nature, as they require artisanal or industrial techniques and certain technologies to be produced. Moreover, novel materials have specific functions, even if these are just of a symbolic or religious character. Such functional materials and human artefacts are thus also considered to constitute “technofossils,” adding to natural fossils of previous geological epochs. Technofossils, synthetic materials, and human-designed mineralogical species now do not just populate the “critical zone” of life on Earth’s surface, but extend from chemicals and structures underground, to manufactured gases in the atmosphere, all the way to orbiting and interplanetary space hardware.

In the mid-twentieth century novel material types exploded both in diversity and in production quantity. The production of concrete, made from portland cement, saw an exponential increase since the start of the Great Acceleration, making it today the most abundant anthropogenic sedimentary rock on Earth. Plastic represents an emblematic case-study to reflect on the dynamic relationship between petrochemistry, economic expansion, and consumption, but also sophisticated forms of cultural expressions which jointly shaped material independency from geobiological matter. A result of scientific efforts of the early twentieth century, mass-produced plastics, such as polyethylene and polypropylene, are essentially a post-Second World War phenomenon. With the availability of cheap oil, polymer-chain products became a signature material for modern life in the 1950s, an innovation capable of establishing mass consumerism and a form of “material democracy.” As a result, microplastics can now be found in the most remote areas, in our bodies, and even on the moon. Similar “histories of stuff” can be drawn from many other novel materials: asphalt covering vast stretches of ground; volatile glass microspheres used as additives in paints and coatings; aluminum, which in fact exists on Earth only in combined mineral form, and is now being mass produced at a rate of more than 60,000,000 metric tons every year.

Earth is undergoing a rapid human-mediated mineral evolution and diversification. As a consequence, modern materials science and industrial production are accentuating the given chemical disequilibrium on Earth to an extent never seen before. This dossier explores the material contexts and scientific accounts of this geohistorical anomaly, discussing novel materials and technofossils in their connection with material culture and human-impacted environments, and how these bear stratigraphic evidence of a twentieth-century transition into the Anthropocene.