Measuring Loss

Claims/Property seminar reflection

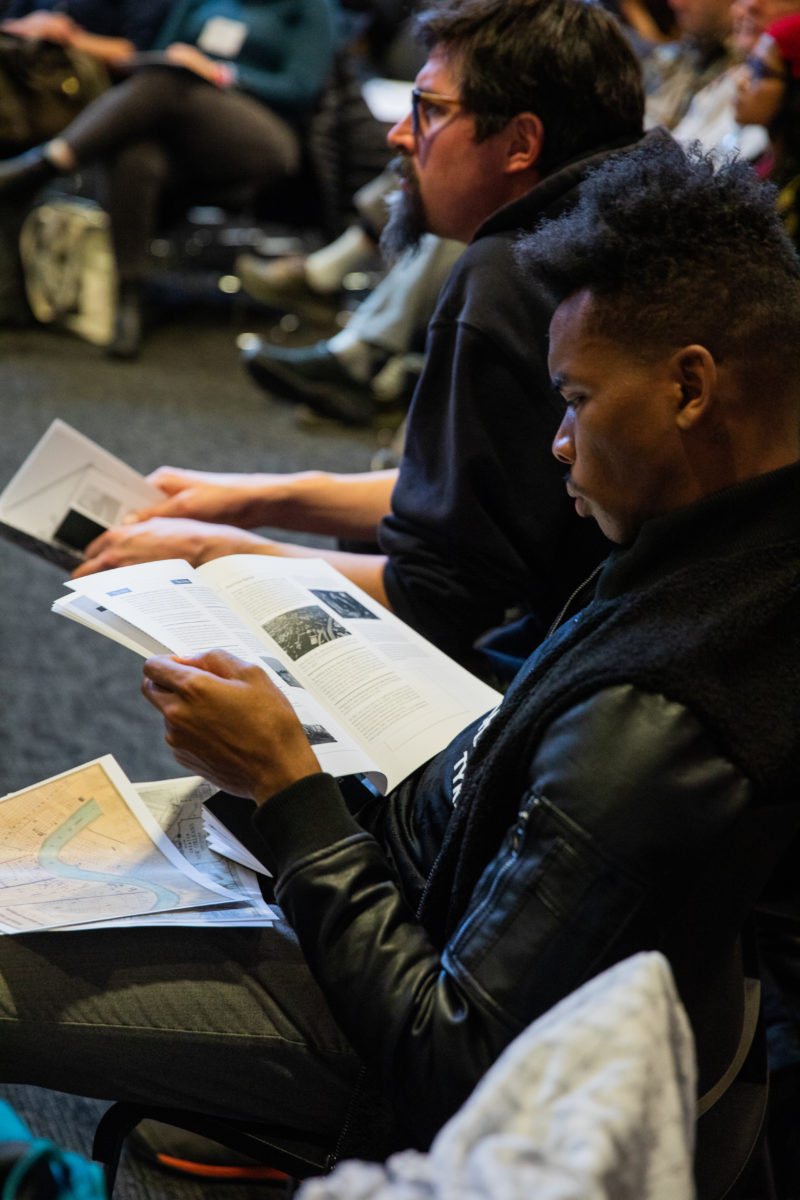

The Anthropocene River Campus seminar Claims/Property engaged with the complicated entanglements of property claims that cut across the social, racial, and ecological landscapes of the Mississippi Delta. In this seminar reflection, Sarah Lewison describes undertaking a participatory investigation of New Orleans and nearby Terrebonne Parish as a territory, in an attempt to apprehend the concept and consequences of property—which we might consider “more social practice than thing.” From the historic and ongoing systematic dislocation of New Orleans’ Black population, to the efforts of the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, who have lived for generations in kinship with a now threatened landscape, to secure Federal Recognition, the seminar made clear the differences between living with place and making property. Informed by these encounters, Lewison advocates for witnessing these injustices as a means of not just measuring loss, but preparing for repair.

The Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe’s community center in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, where land is lost at the rate of a football field every hundred minutes—a new increment of time to measure the velocities of change in the Anthropocene. Photograph by Sarrah Danziger

Long before it will become someone’s property, this place is a salty inland basin that fills and empties over long intervals, drawing down silt and nutrients from hot equatorial forests that feed teeming microscopic life forms, the precursors to oil. Much later come intervals of extreme cold, years of glaciers advancing and retreating, and then finally a melt. Some people on this continent know of the ice from their ancestors’ stories. Now, around 2500 BCE, the Mississippi River is really starting to get going, moving its fresh water and silt down a slow grade, carving and filling land, avulsing into new channels, and dumping successions of sediment loads in lobes of soil that extend into a sea. Small bands of people move through and live on these spits and marshes, gathering shellfish, hunting; some are the predecessors of people who still live here, while others leave only remnants of their occupation in shell middens and mounds. A rich time; buffalo graze all the way down to the gulf. A thousand years from now, in 1540, an adventurer from afar named Hernando de Soto will drift down the Mississippi and leave his remains as well. Another hundred years pass, and the French explorer Robert de La Salle takes his turn to float down the channel. He claims the land, valley, waterways, trees, bayous—all of it and more—for France.

The terms “claims” and “property” compose the title of a seminar convened during the November 2019 Anthropocene River Campus to investigate how cultures of property support, infiltrate, and inform processes of the Anthropocene. This topic emerged from a process of collective analysis and writing at the Anthropocene River Midway Meeting in St. Louis in the spring of 2019. As seminar conveners, we hoped not only to address land as property but to draw out gray zones of epistemic significance, such as how the practice of property sees all life as its potential object. Indeed, the pervasiveness of property and its sedimentation through both space and time made it difficult to settle on a plan. For one, how were we to pursue a subject that is more social practice than thing? Neither “property” nor “claims” can be observed as material or infrastructural projects, such as a dam, hospital, prison, or school can. Yet property provides the economic and political underpinnings for such projects—whose benefits are subsequently unevenly distributed.

To think about property is to think about its political predisposition and social effects as part of a broad and subjective variegation of emotional charge. Who is able to have access to or “make” property, and how, and for what purposes? Claims, whether to territory, speech, or narrative, are likewise enunciated by social subjects and infused by feelings. We needed to encounter the narratives and feelings that generated these claims. But it seemed paralyzing to imagine how, and with whom, especially for those of us who live far from the context of New Orleans. And for some, our identities also mattered, as white people from settler or immigrant ancestries who enjoy advantageous property relations through no efforts of our own. We recognized that contingencies and differences between people are symptomatic of and charged with the full weight of the contradictions and inequities issued in society. Our initial conversations hovered on the sticky questions of how the historical making of property has disproportionately negated the existence of some more than others—the same people who suffer environmental vulnerability, and political and economic exclusion. It seemed important, then, to situate our seminar’s practice as one of observing and listening to these experiences, even though imagining such conversations with roughly thirty people beyond our initial convening group (Morgan Adamson, Bruce Braun, Ravi Agarwal, Shana M. griffin) seemed overwhelming.

We did not want to use the form of a tour, because claims and property, rights and access, are precisely the facts that tourism conceals. An investigation into place should instead entail learning about the means through which people are able to animate that place to make it home, and the obstacles that prevent that. We decided to explore New Orleans as a territory alongside our hosts, experts, and conveners. We leaned heavily on the knowledge, generosity, and affinities of Shana M. griffin, Grace Treffinger, Geneva Leboeuf, Laura Kelley, and Nathan Jessee. We reflexively reframed our questions about property and claims through listening to their experiences, divulged formally and informally, walking, eating, and being together.

My use of the word “territory” is inflected by Claire Pentecost and Brian Holmes’ concept of the “continental drift” as a participatory investigation of place and daily life shaped by interdependency at different scales, from the minute to the global. Pentecost describes “five scales of contemporary existence: the intimate, the local, the national, the continental and the global,” with “territory as the matrix for our connection to others and to the earth.”1 Territory thus offers a way to attend to differentials of experience across scales of affect, allowing property and claims to be seen self-reflexively but also as part of complex geopolitical assemblages laden with difference and injustice. How might a collective listening practice take in and resonate feelings of injustice in order to raise their volume and urgency? What would it take to facilitate the reparation of such losses? Injustice demands to be heard and to be witnessed, and to be felt, in order to prepare for repair.

Indigenous feminist scholar Dian Million cites the importance of the personal, felt narrative in building political power among Indigenous victims of state violence. In recounting the ways in which Canadian Indigenous rights commissions have compensated victims of displacement and violence, she lambasts the short-sightedness of a reconciliation process that fails by its ultimate refusal to restore Indigenous sovereignty.2 How can allies address such failure? In listening, we are called to witness the insidious moves, from the local to the global, through which property is made and leveraged, and the ways it alienates and disenfranchises. To witness is a kind of labor that necessitates making more room in the self for the trauma of others, to open the imagination to more ethical practices of place. What follows is my chronicle of the two days our “Claims/Property” seminar traveled, conversed, felt, and thought together in New Orleans and in Terrebonne Parish.

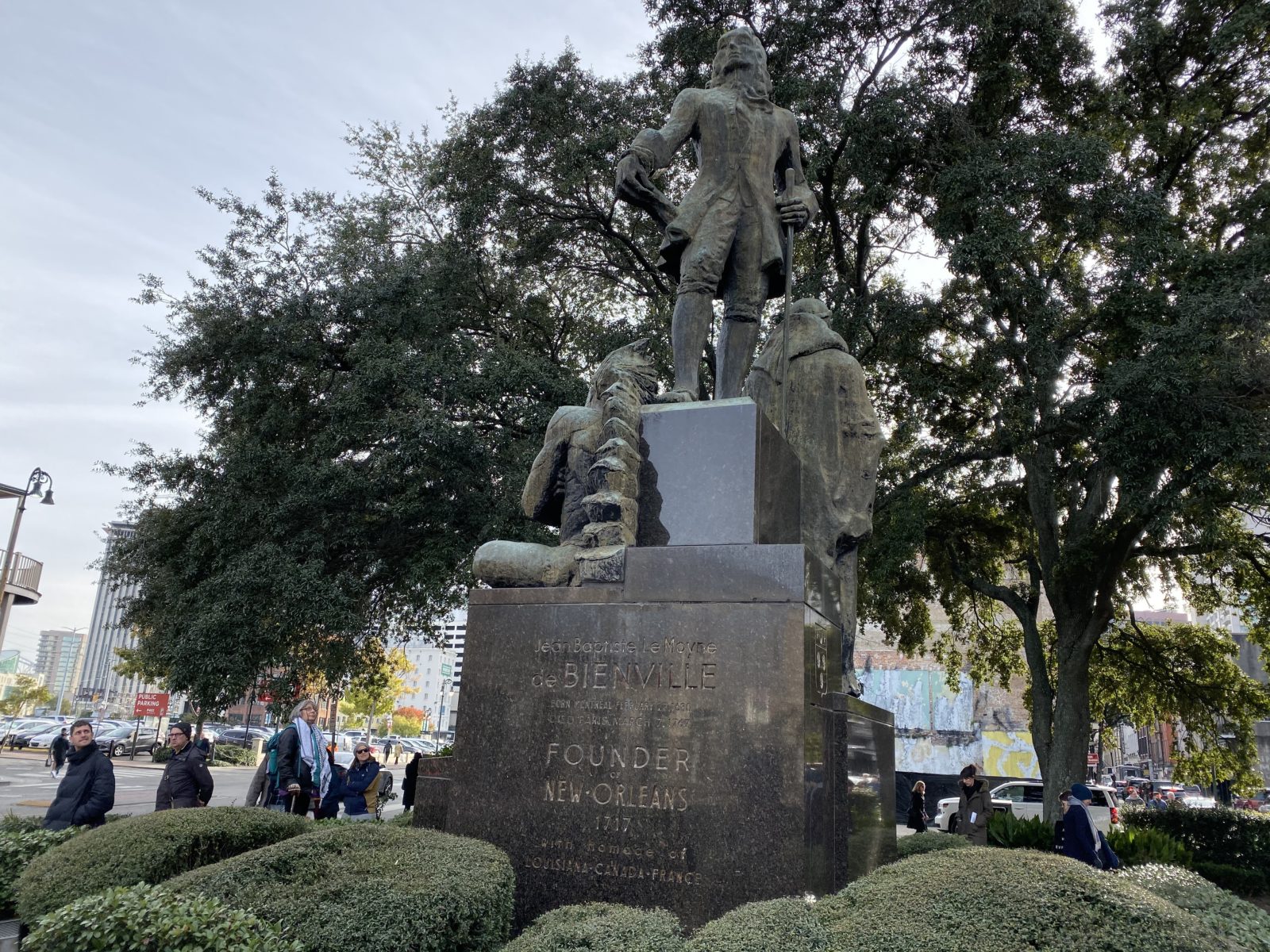

The bronze statue of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville in the French Quarter, the colonialist who founded New Orleans in 1718, Photograph by Carlina Rossée

We begin with a walking tour, “The Geographies of Black Displacement,” produced by fellow seminar convener Shana M. griffin, an activist and scholar. The Geographies of Black displacement is a multimedia and public history research project that illuminates the systematic dislocation and denigration of New Orleans black populations, from the period of enslavement, through shifting housing policies, to forms of racialized violence and confinement. Shana’s research has informed her work as a housing activist and community organizer. We get to experience this profound project as a guided walk through the oldest areas of New Orleans. We stop first at the bronze statue of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the colonialist who founded New Orleans in 1718. The monument, a gift from France, stands in a small park. We consider the trio of figures: Bienville, the tallest, faces the horizon, while beside him his companion, the Augustinian monk Father Athanase, looks down at a bible. At Bienville’s feet sits an unnamed Indigenous man with a feathered pipe in his hands. One looks toward a future, the second to Divine Law, and the third is a cipher.

On the nearby river levee, we take in a new marker installed for the city’s 300-year anniversary. The information panel, titled “Transatlantic Slave Trade to Louisiana,” tells us that in the same year the city was founded, two ships left Africa for New Orleans with 451 people in bondage. They arrived on these shores in 1719. The plaque continues, “Their skills and cultural practices were foundational to the development of Louisiana.” The marker cites their origins, humanizing them as cultures, nations: “Wolof, Bambara, Mandingo, Fulbe, Nard, Ganga, Kissy, Susu, Mina, Fon, Yoruba, Chamba, Hausa, Igbo, Ibibio, Kongo/Angola, Makwa.” They were, the panel says, cargo, “unloaded here on the banks of the Mississippi River.” Shana mentions that the ships could be smelled two weeks before arrival because of the conditions on board. These people built the young city and the levees that kept it from flooding; property making property.

A marker installed on New Orleans' riverfront for the city’s 300-year anniversary, giving information about the transatlantic slave trade. Photograph by Camille Lenain

Shana sets us to reviewing American history. In 1803, having failed to stop the revolution in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), France sold its continental territories to the United States. Settler agriculture expanded into these ancestral homes of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), and other nations, who were forced to move elsewhere. Some found their way to the bayous of Louisiana. Meanwhile, three technological advances transformed agriculture: the steamboat, the cotton gin, and granulated sugar processing. Together, they intensified the demand for unfree labor. In 1804, Haiti became an independent nation, and nearly 10,000 Haitian refugees, including sugar planters, enslaved people, and free Blacks, migrated to New Orleans.

Four years later, in 1808, the United States abolished the international slave trade. This gave rise to a domestic market known as the “second middle passage.” Enslaved black people were transported up and down river by boat, or even forced to walk from Virginia or the Carolinas to New Orleans markets. In 1812, Louisiana became a state. Eventually, 400 plantations were established between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, giving rise to the highest concentration of millionaires in the United States. By 1820, the city was the biggest market for slaves in the country. Sales took place in private homes, on street corners, inside banks, insurance companies, schools, and hospitals. “Slavery, sex, and sugar” became New Orleans’s primary tourist attractions. Shana conjures this past through her incantation of the everyday. Partying tourists cruise by us as we look for traces of slave quarters along the side of an old building. These were tiny rooms where enslaved people were quartered when an owner stayed in the city. The cubicles were situated close to the slaveowners’ apartments, and they could enter any time for any reason. We visit buildings with markers indicating that they were used for selling humans. Shana points out how the spaces and the laws that controlled the movement of enslaved people are the templates for contemporary carceral systems, and how the city’s architecture reveals these spaces of confinement for those who look. Between 1804 and 1862, around 135,000 people were bought and sold in New Orleans. This number does not account for the unquantifiable – the love, kinship, and stability that was destroyed, and continues to haunt the present.

Shana M. griffin talks to seminar participants in New Orleans' French Quarter, pointing how the city’s architecture reveals spaces of confinement—a legacy of slavery—for those who look. Photograph by Sara Black

Due to New Orleans’s Catholic provenance, the city had also customs that made slavery look different than elsewhere in the U.S. Enslaved people had Sundays off, and, intermittently according to policy changes, the right to earn their own money. Although white lawmakers attempted to control the practice, affluent Blacks could sometimes purchase their family members. In 1812, free people of color began buying parcels of land from Claude Tremé, who had inherited a retired plantation through his wife, Julie Moreau, who, as a woman, could not own property. The district named after Tremé, often referred to as the oldest neighborhood of free people of color in the U.S., served as a site of economic, cultural, political, social, and legal events that shaped the struggles of people of African descent in the South and across the United States. Tremé was home to some of the city’s most successful and talented black artisans, craftsmen, musicians, doctors, teachers, writers, revolutionary abolitionists, and activists. Today, some residents still live in houses built by their ancestors. The New Orleans Tribune, the first black daily newspaper in the U.S., was started by physician and publisher Louis Charles Roudanez, a resident of Tremé. During the Reconstruction era following the American Civil War, the residents of Tremé and other neighborhoods engaged in advocacy efforts in the city and across the state to expand civil rights protections, increase access to schools, public institutions, employment opportunities, and integrated transportation systems. Once Reconstruction ended, and federal troops withdrew, Jim Crow laws reversed the gains Black residents had achieved in terms of equality, wealth access, legislative representation, and dignity.

Our tour continues on the edge of Tremé, where Bienville Basin, a new “mixed-income” housing complex, has been fashioned from the destruction of an older low-income project, Iberville Public Housing. Shana lived here as a child. We stand near the renovated buildings with her. She lets us know the protocol: “I am taking you in because I lived here, and then I will take you out.”

Social psychiatrist Mindy Fullilove uses the gardening term “root shock”3 as a metaphor to describe the severe psychological damages Black communities suffered from being uprooted as a result of mid-twentieth-century urban renewal projects. Starting in the 1930s, integrated neighborhoods like the Tremé began to be torn down through policies of slum clearance, and people were relocated from their familiar neighborhoods and into segregated public housing. The intersectional social bonds that characterized their former neighborhoods were torn apart. The houses that still stood suffered from neglect because investment redlining practices made it impossible for owners and new buyers to get loans. Shana describes to us four different “urban renewal” projects in the Tremé that have uprooted families and destroyed social cohesion. When Interstate 10 was built in the late 1960s, more homes were lost and 500 businesses had to close. I read that hundreds of ancient oak trees lining Claiborne Street, which led to the freeway, were uprooted and carried away. Reflecting beyond Shana’s account of systematic localized forms of displacement, and guided by Fullilove’s analysis, I imagine how New Orleans would have been impacted by the regressive policies of Reagan’s 80s. U.S. cities during this period were slammed by the closure of mental health facilities, the halving of Section 8 housing subsidies,4 and covert federal-level entanglements with extranational cartels that led to the rampant distribution of highly addictive substances in the U.S. All of these factors would contribute to difficulties within any community, but they hit black communities the hardest.

After Hurricane Katrina scoured New Orleans in 2005, even more public housing was razed, never to be replaced in the same numbers. Anthropologist Roberto Barrios writes about how, post-Hurricane Katrina, residents invited to planning sessions with city planners and architects “demanded that lightly damaged public housing be reopened immediately,” to “prioritize(d) the reinstatement of the city’s pre-Katrina population—especially renters and economically marginalized African Americans.”5 Shana’s research emphasizes how black homeowners were discriminated against in the post-Hurricane Katrina period because their homes were often located in lower-lying areas and consequently were assessed below replacement value.6 Because of this, the Federal Road Home grants that were intended for returning homeowners didn’t offer Black residents enough money to rebuild. Fullilove asserts that when people are confronted by “disaster upon unmitigated disaster,” with no chance for recovery, they lose hope and have no choice but to fend for themselves in any way they can. The legal fact of property ownership does not protect those whose lives and futures are considered disposable.

“The soul demands freedom. If it cannot fight, it will argue. If it cannot argue or persuade it will dance. It will sing. If reason is denied, then art must arise. In a sense the Negro did not create jazz; he was jazz.”

—Edward Bland, The Cry of Jazz, 19597

It is dark when we reach our last stop, Congo Square, a commons used by enslaved and free people of color as a market and gathering place for music and dancing since the early French days. Haitian refugees also worshipped, drummed, and danced here. Congo Square is cited as the birthplace of jazz. Today it is enclosed within a 31-acre pleasure ground called Louis Armstrong Park, with gates that are locked each night at 6 p.m. Twelve blocks of residential housing were torn down to build the park. Shana’s words come to mind: “Once you displace a community, you are confining them somewhere else.”

The morning is cold and drizzly. We get back on the bus, rise above the city via Interstate 10. Shana speaks about how her work with women’s health, incarceration, and housing discrimination led her to housing activism and to establishing a community land trust. Reproductive justice, Shana proposes, must go beyond the site of the individual reproductive body to include all that is needed to support the stability necessary for a parent to care for their children. Gender studies theorist Michelle Murphy has written extensively about such a recasting of reproduction, using the term “distributed reproduction” to account for the “state, military, chemical, ecological, agricultural, economic, architectural” infrastructures that determine intergenerational reproductive prospects. Murphy continues: “Within such infrastructures, some aspects of life are supported while others are abandoned. Infrastructures promote some forms of life, and avert others. Through infrastructures, some forms of life purposefully persist, while other forms are unintentionally altered.”8

We are traveling to Terrebonne Parish to meet with Geneva Lebeouf and the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe. The roads get smaller until we reach a long bayou lined with small houses, trawlers, and packing sheds. We find the tribal community center, an insulated Quonset hut–style building on tall piers, and climb up into a light-filled lodge and the exquisite smell of cooking food. In back, a kitchen bustles with people chatting and cooking. Geneva, who facilitated this meeting, greets us and describes the wonderful dishes they have made from seafood caught by tribal members: Shrimp opelousas, étouffée, gumbo, and Brenda’s famous baked fish. There is palpable pride in the room for the research they’ve been doing into their heritage. The walls are covered with maps, informational posters, photographs, and books. Geneva introduces Theresa and Donald Dardar, Mary Verdin, Brenda Billiot, Christine Verdin, Earl Billiot, and others who have come for the gathering. We also meet Laura Kelley, a historian from Tulane who has worked with the tribe for over five years, bringing students to document oral histories and traditional knowledge—crucial archival work that will contribute toward the tribe’s bid for federal recognition.

For generations, the Pointe-au-Chien have shrimped, crabbed, fished, trapped, and hunted for subsistence, supplemented by grazing beef cattle, foraging herbs and fruits, and cultivating gardens. Today, many members are also commercial fishers, boat pilots, and schoolteachers. Their tools are contemporary—shrimp boats, seine nets, crab pots, and the internet—but they are still bound by kinship to each other and the littoral landscape. Geneva describes for us the tribal governance and her current role in it; as part of the membership committee, she studies the genealogies of people associated with the tribe. To be a member, one’s parents or grandparents must have lived in Terrebonne Parish in both 1940 and 1960. This interval of residency takes into account the flooding that has periodically displaced folks to other locations. “There’s a lot of people in our community who have moved to higher ground,” Geneva says. “But they always move back.” After introductions, we get to the delicious food, eating in small groups to hear stories about our hosts’ children, fishing, tribe, and home.

The Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe’s community center in Terrebonne Parish. Photograph by Sarrah Danziger

We join Geneva behind the community center to see open water where there once was solid ground. They say land is lost at the rate of a football field every hundred minutes—a new increment of time to measure the velocities of change in the Anthropocene. Land disappears on a daily basis to erosion and subsidence, which is then exacerbated by storms and rising sea levels. The changes can be traced to policies that unleashed slow-moving, positive feedback loops of unnatural disaster, such as the Swamp Land Acts of 1849 and 1850, which turned federal wetlands over to states for agricultural use. Nathan Jessee, a PhD candidate studying the relocation process of the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, explains how those acts were “central to Louisiana making property out of this ‘uninhabitable swampland’ and setting the stage for private property development and extractive industries to come in.” In Louisiana, nine million acres of mixed wetlands were auctioned off for less than a dollar an acre, snapped up for timber and oil. Every canal that has ever been dredged through the swamp for logging, pipelines, construction, and exploration persists like an open wound, one that increases vulnerability to storm surges, hurricanes, erosion, and salt inundation. Every barrel of pumped oil augments the metabolic intensity at which the transformation proceeds. The engineering of the Mississippi River has also played a role—“straightjacketing it,” Laura Kelley says, referring to the leveeing and shortening of the river that eliminated the surges of sediment that once built land. The constitution and ecology of the water itself is changing; Geneva says the water was never salty enough for dolphins before. And the introduction of new compounds, such as Corexit 9500A, the solvent used after the BP oil spill in 2010, has intervened in the reproduction cycles of crabs and oysters.

Despite the challenges they face, Pointe-au-Chien members are committed to cultural survival, as opposed to simple adaptation. The recent installation of a new levee, lock and floodgate system part of a larger project to protect Terrebonne and Lafourche Parishes from storms, will benefit the Pointe-au-Chien community. In contrast, the nearby Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, who live outside of the levee system, has been preparing to relocate for almost two decades.

Our bus crosses the levee via the two-lane Island Road, surrounded by open water dotted with oil and gas pipelines and pumping stations, and enters Isle de Jean Charles, a long strip of land with a smattering of homes belonging to tribal members. Since the 1950s, the band has lost 98 percent of their ancestral land, and now inhabits only a remnant—a narrow spit surrounded by water. As with the Pointe-au-Chien, many families from Isle de Jean Charles have moved inland due to the extreme flooding, but in this case, it’s clear they will never be able to move back. After undergoing a long-term study and design process, the Isle de Jean Charles band Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe applied for and was awarded a Federal grant for resettlement due to climate change- the first such community in the United States. They call their resettlement “a living and active bridge from our ancestral Island, which is rapidly eroding, to a sustainable future.” The new inland site will include a community center, seed library, museum, gathering areas, and housing to bring the tribe together around cultural regeneration. But the involvement of federal money has brought complications; we learned from Nathan, that there is uncertainty as to how and whether the ambitious resettlement will be accomplished without eroding the tribe’s ability to retain self-determination over their own future.

Driving along Island Road, toward Isle de Jean Charles. Photo by Sarrah Danziger

The bus cruises to a pier at the end of the strip, turns around and heads back toward Island Road and Point-au-Chien. Scattered among the low-lying wood-frame residences of tribal members are houses that were built more recently by what Geneva and Laura call “weekend warriors.” We also saw these vacation outposts on Bayou Pointe-au-Chien. Built on land purchased by outsiders, they are better maintained, well equipped with recreational toys, and stand higher off the ground. Geneva is irked by the weekend warriors. I witness her annoyance and try to make sense of it. Returning to the pier at Pointe-au-Chien, Geneva gestures toward an island that is home to the ancient mounds and burial sites of their ancestors. For the Pointe-au-Chien Tribe, the history and life of their territory has its own claims on them, to which they are accountable. The weekend warriors have the luxury of a vacation retreat to use for a few days of hunting and fishing with the boys. It barely constitutes a relationship, for they have no responsibility to the place, which in turn has no claims on them. For the Pointe-au-Chien, to maintain material relations with place and each other includes attending to the needs of the ecosystem. Last year, the tribe obtained a grant and organized volunteers to construct a massive artificial barrier reef of oyster shells to protect the ancestral mounds. The reef will also provide surfaces for oyster spat to attach to and develop on. To be cared for by place obligates reciprocity, in this case for ancestors and oyster kin.

Both the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe and the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe are legally recognized by Louisiana state as unique tribal peoples with long histories in this region. They are both currently immersed in the application process for federal recognition, a notoriously difficult process that can take as long as 30 years. To be acknowledged as a tribe on the federal level, they must compile detailed evidence of their membership, genealogies, treaties, language, and governance for each decade of the twentieth century. The application takes the form of a narrative drawn from maps, diaries, letters, oral histories, and other archival materials. The coveted designation of federal recognition make a tribe eligible for multiple support services and grants. While there is no equivalency between what Indigenous Peoples have lost and the assistance available through federal recognition, the acknowledgment process at least affords tribes access to resources that may mitigate historic harms. It can support them in transitioning the climate catastrophe and increase their capacities to thrive in the next times.

For Black Americans, there is no application for the restitution of property they were swindled out of or forced to relinquish, or for the countless hours of stolen labor that augmented the wealth of others. There is no administrative process through which Black people can be aided in the restoration of languages and lost cultures. There is no recognition process that makes them eligible for reparations. Author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates writes in his essay about reparations that “we find the roots of American wealth and democracy … in the for-profit destruction of the most important asset available to any people, the family. The destruction was not incidental to America’s rise; it facilitated that rise.”9 Though there is currently no process for calculating reparations like the one used to recognize indigenous loss, the recognition process could be reconfigured to account for and become a witness to the unseen deprivation that underpins property.

While identity is performed through and in place amid processes of living with place, making property is a violent and arbitrary operation inevitably drawn from European-colonial cultural mores of domination, individualism, and hierarchical entitlement. When Robert de La Salle claimed the Mississippi River Valley for France, he preemptively dismissed prior claims of other human and beyond-human inhabitants who already were using the land for their own purposes. When petroleum companies availed themselves of the marshes auctioned following the Swamp Act, they set cascades of devastation in motion—the side effects of progress.

Each of us is impacted by these side effects; they reach us through the mediums of air and water, and the effects of weather and infrastructure. They are embedded in the quotidian and the necessary; in access to food, housing, health, protection, community, and mobility. They surface as policy through the working of capital and as its externalities, and yet, they touch us differentially, in line with our identities, family histories and life trajectories. For two days, thirty-odd people have listened to the experiences of our guides. Being in proximity with each other on long bus rides and straggling walks, there has been time for introspection, sensing, conversation, reflection, and comparison. Who are our kin? Where do our reciprocal relationships lie? What infrastructures do we rely upon? How did we come to the place where we live, and through what stakes, claims, and losses? What are our “preexisting conditions”? We may share an understanding of property’s injustices under capitalism, but we do not equally share their consequences.

After two days of itinerancy, the seminar gathers in a large room to exchange impressions regarding how property is defined, made and unmade. Breakout groups grapple with the contradictions within ownership’s promise of stability given the realities of dispossession. How might we configure relations that are founded upon mutual social responsibility, rather than upon forms of ownership that sever the lives of others?

One group, meditating on the origins of property in possessive individualism, plays with the idea of “multiplying the subject,” coming up with “possessive collectivism” as, perhaps, a scaling up of the community land trust. I was thinking of this when I started this essay, but misremembered their term as “collective possession,” which I thought of in the sense of a possession by beyond-humans, who could be either allies or demons, ancestors, or an ecosystem, a possession from outside the subject, that goes two ways. I imagined the reshaping of possession as multivalenced, having neither owned nor owner, but guided by a jurisprudence of reciprocity and radical equality.

Before we had arrived in Terrebonne Parish, environmental photographer Ravi Agarwal had asked us to think about protocol as we enter the space of another. What attitudes were we coming with, what it is that we might take, and what it is that we might give in return? In our seminar wrap, Shana offered the idea of witnessing as an act of reciprocity. This is because witnessing takes labor. It takes commitment and energy to consider the circumstances of another. Perhaps this modest starting place can be the beginning of another kind of journey. In their performance work Viewing Hours (2019), Mayfield Brooks speaks about the unredeemed labor of witnessing:10

After the viewing hours I would like you to commit to a practice of witnessing what you see. You are responsible to commit yourself to this practice as a move toward reparations, and as you know, repair work takes centuries. You and I will not live to see the repair work completed but you can still be a witness.

Thank you to co-conveners Morgan Adamson, Ravi Agarwal, Grace Treffinger, Shana M. griffin, and Bruce Braun for their brilliance, focus, and camaraderie, to Nathan Jessee for sharing his insights and research on the Isle de Jean Charles Band, to Geneva Lebeouf for her wisdom and time, and Carlina Rossée for keeping the seminar on the rails. Special thanks to all the participants.

- Roberto E. Barrios, Governing Affect. Neoliberalism and Disaster Reconstruction. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017.

Nicholas Blomley, “Law, Property and the Geography of Violence: The Frontier, the Survey, and the Grid” in Annals of the Association of American Geographers, March 2003.

Judith Butler, The Force of Non-Violence: The Ethical in the Political. New York: Verso, 2020.

“Federal Recognition of Indian Tribes” Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, June 23, 2015

“Federal Recognition,” National Congress of the American Indians.

“Free People of Color in Louisiana Revealing an Unknown Past.” LSU Libraries.

Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw website.

Elizabeth Kolbert, “Louisiana’s Rising Coast” in New Yorker Magazine, March 25, 2019.