Revisiting Regionalism in the Mississippi Basin

The kinetic energy of the flow of the Mississippi River presents a latent source of hydro-electrical power. In the past, ambitious attempts to utilize the hydraulic capacities of the Mississippi River basin and to develop a regional electric power system have gone unrealized. This project re-constructs the history of infrastructural regionalism and examines the concept’s potential for future reforms and policies.

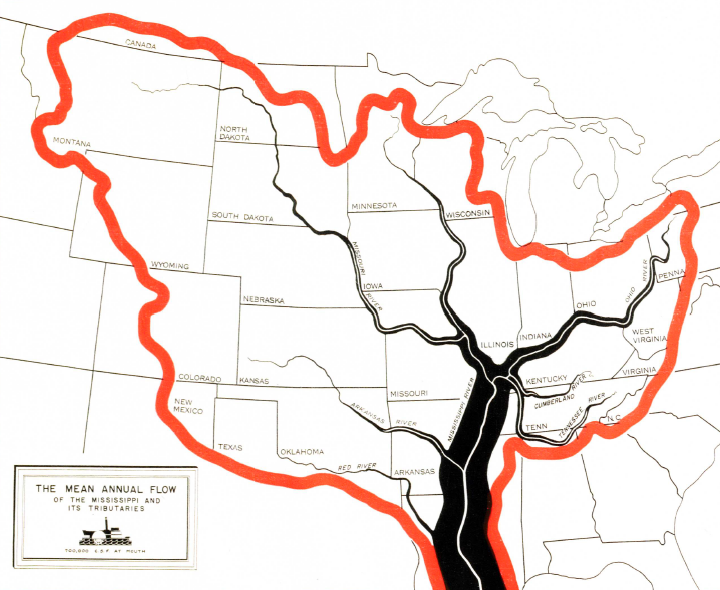

This project extends the frame of analysis to consider the Mississippi not just as a river but also as a vast watershed occupying 40 percent of North America’s landmass. A wide, shallow basin, its topography concentrates rainfall into tributaries that conflate and become the major rivers constitutive of the Mississippi. Flowing southward from the modestly elevated Lake Itasca at just six cubic feet of water per second, the river eventually discharges at nearly 700,000 cubic feet per second into the Gulf of Mexico. Considered at this scale, the river can be conceived of, not only as flowing water, but also as a vast concentration of kinetic energy.

Drawing on the sciences of hydrology and ecology, in the first half of the twentieth century visionary regional planners—from geologist John Wesley Powell to conservationist Benton MacKaye—similarly conceived of rivers in energetic terms, albeit in a pragmatic way. MacKaye in particular proposed that the latent energy in the hydrological cycle should be harnessed for the production of electrical power, and that powerlines should be “extensions of rivers.” In contrast to the linear trajectory of fossil-fueled industrialism, working with Earth’s cyclical flows seemingly offered an elegant solution to the provision of power, with rainfall and riverine gravity providing electricity without end.

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is the most well-known outcome of such thinking. Begun in 1933, the flagship project of President Roosevelt’s interventionist “New Deal,” largely succeeded in providing low-cost hydroelectrical power via a “seamless web” of dams and plants. But for its most ardent supporters, the TVA was envisioned as the first in a continent-wide network of river valley authorities. As the TVA’s resident philosopher, MacKaye argued that the Ordinances of 1787 had wrongly divided the continent according to the territorial ambitions of European colonizers. In place of states, MacKaye called for “watershed democracies,” a nation reterritorialized according to regional hydraulic capacities.

President Roosevelt and his advisor, Morris Cooke, came to believe that the entire Mississippi Basin could operate as a single regional system. Coordinated and centrally planned, the basin was believed to demarcate the boundary by which the provision of electrical power, irrigation, transport, and recreation should sensibly be conceived of. The ambitious but unrealized plan to create a Mississippi Valley Authority (MVA) has been all but forgotten today.

Drawing on the history of energy and histories of planning, this research project will reconstruct the history of this plan. It will revisit the “geotechnic” philosophy of MacKaye, the plans of the Public Works Administration and Mississippi Valley Committee, the maps and hydrological surveys, and the blueprints of a similarly unrealized postwar plan for the hydroelectrification of a part of the Mississippi Valley, the Missouri Basin.

The project’s intention is to do more than offer a counterfactual history. By resuscitating this unrealized plan, the hope is to bolster contemporary visions of a green New Deal by demonstrating the feasibility of such ideas in the past. In doing so, a central question will be how infrastructural regionalism can be revived in the Anthropocene, and how this might be carried out without repeating the mistakes of the large-scale river engineering projects of the past.