When the Signal Disappears in the Noise

Geology of a Floating Present

There is no clear signal-to-noise ratio when it comes to classifying and reacting to the existential shift now underway. In this political commentary, Anthropocene historian and curator Christoph Rosol reflects on the disturbing schism between geoscientific insights and the info-capitalist modus operandi diluting these insights to mere noise. Are we ready to comprehend what the Earth has already recorded? Are we structurally equipped for what is already happening?

Courtesy spurloser

The goal of chronostratigraphy—the study of layered rock, soil, and other strata in relation to time—is to separate the signal from the noise. Fixing a temporal horizon in the abundance of geological time means following a complex path of isolation and purification of empirical data as well as institutional procedures. Technical practices of exactitude—measuring, dating, counting, interpolating, and calibrating—join the formal criteria of disciplinary and institutional conventions in order to choose, collectively filter, and eventually determine a consensus for a stratigraphic reference point marking a boundary in the geological time scale. If it plays by these rules, the chronostratigraphy of the Anthropocene is no different. Inherited formal criteria, sophisticated equipment, and group discussions among experts structure those evidence-finding procedures of isolation and purification that end up defining the strongest signal for the onset of the present epoch.

Yet once the process is completed, the fate of this signal is to be engulfed and diluted again by the noise of societal indifference. In contrast to the enclosure strategy—or really, epistemic salami tactics—of stratigraphy, the communicative praxis of our current societal relations is one of continual signal multiplication, amplification, and manipulation. The result is a clamorous cacophony that drowns any meaningful signal in a noisy sea of babble. Within the cascading planetary crisis, an explosion of information and an implosion of clarity directs a continuously-expanding patchwork of temporal truth and generic discord, of contradicting priorities if not cultural wars. What used to be regarded as the foundations of modern democratic societies—plurality and cultural liberalism guided by rationality and consensus—is now undermined by an ever-finer arsenal of commercial and political exploitation of information streams, resulting in a highly fragmented and affect-driven battle space still euphemistically called “the public” or “society.”

This commentary on the yawning gap between the tradition-laden search for solid empirical evidence of the Anthropocene and the shaky ground on which this evidence falls back upon does not intend to indulge in a kind of cultural pessimism or reactionary lament about the demise of liberal ideals in the face of the information society. The gospel of the liberal foundations of modern democracies cannot stand any historical test of actual power relations, nor is complexity reduction a good maneuver for dealing with the mutually interdependent crises of today, especially when one looks at the “simple answers” that autocratic regimes tend to offer. If anything, plurality and cultural diversity have increasing value in these times when slowing down and reverting the worst trajectories of the Anthropocene is what matters most. Resilience and repair rest on multiplicity and redundancy, which is as true for ecologies as it is for societies.

Instead, this essay mainly attempts to share an observation about the glaring blindness to the signs on the wall—or more precisely, in the sediments, ice cores, and peat bogs—and open a discussion about the possible sources of the structural incompatibility between the Anthropocene signal and the cacophonic noise that we all have come to participate in and thrive on in our “early-stage Anthropocene” cultures.

The Anthropocene signal: A geology of the present

The practical task of the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) is to define the age and location of the stratigraphic horizon that marks the beginning of the Anthropocene according to the formal criteria of chronostratigraphy. To do this, the group must present clear material evidence that is based on so-called chronostratigraphic markers: physical, biological, or chemical indices that allow for the identification of a distinct and globally-synchronous lower stratigraphic boundary of the new geological epoch.

In such a chronostratigraphic perspective, the signs of the Anthropocene are present in various biotic and abiotic geological profiles: in sedimentary deposits in lakes or estuaries, peat sequences, ice cores, speleothems, corals, and many other environmental archives. As storage media, these deposits record human impacts on natural systems. They register, each in their own way, the various signatures of a given impact: chemical contaminations, atmospheric emissions, combustion residues, radiogenic pollution, etc. What makes these material signatures markers of the Anthropocene is their generic mobility and hence global ubiquity: Due to their fine particulate or gaseous forms, they travel along easily with air streams and water currents which disseminate them to all corners of the globe. The Anthropocene is immanently material, and this materiality points to a series of specific temporal trends and material teleconnections—an empirical pattern—the residues of which the AWG is attempting to map and document.

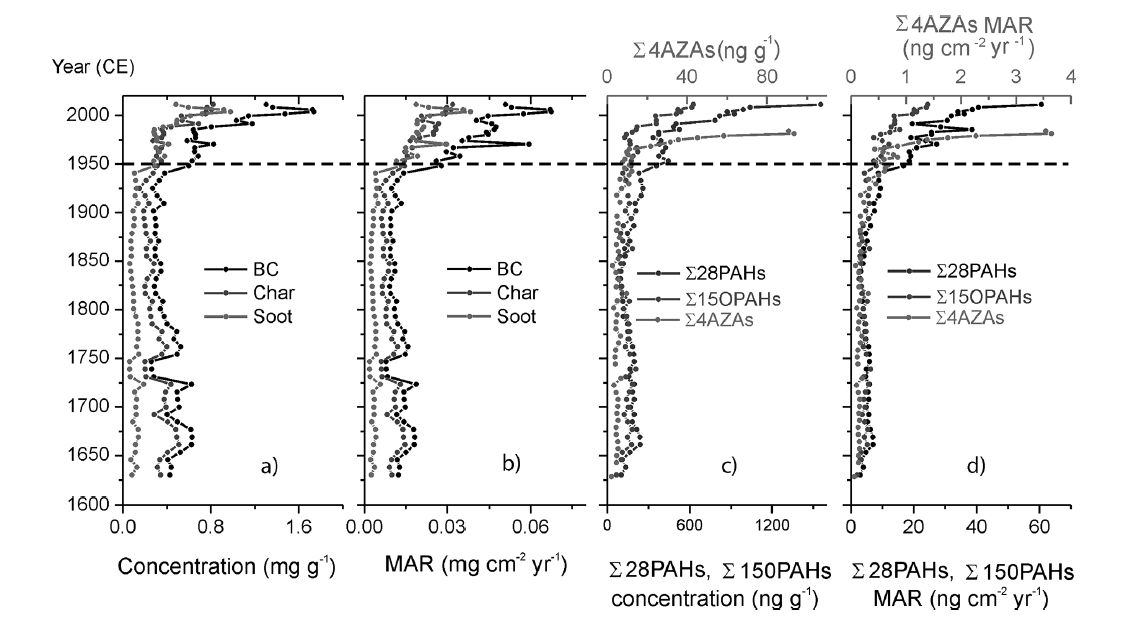

Historical variations of concentrations and mass-accumulation rates of black carbon (BC), char, soot, parent-PAHs, oxygenated PAHs (OPAHs) and azaarenes (AZAs) in the Huguangyan Maar Lake. Source: Jan Zalasiewicz et al., The Anthropocene as a Geological Time Unit, Cambridge University Press, 2019, Figure 2.4.2

Indeed, when Anthropocene geologists unearth the most recent layers in the Earth’s archives, they encounter anthropogenic markers everywhere. No matter where they look—whether at marine sediments from the Seto Inland Sea in Japan or from the San Francisco Bay in the US, at ice cores from the Antarctic Peninsula, lake sediments from Northeast China or Southern Ontario, corals from the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia, or peat sequences from the Sudeten Mountains at the border of Poland and Czechia—their samples show distinct traces of human impacts that are of global proportions.

Throughout the—geologically speaking—very shallow sediment of human history, anthropogenic residues appear at many places and depths; they are scattered, indicative of various levels of intensity, and diachronic, which is to say that they imply changes over extended periods of time. Such archaeological or historical evidence, however, is usually confined to local settings and settlements or constitutes a low-amplitude signal within the background noise of natural processes. The picture changes radically in the upper ends of the core samples where the industrial residues of the twentieth century accumulate. Here, the anthropogenic signals become much more pronounced, materially diverse, and globally distributed, providing a material account of a highly dynamic transformation of not only a local site, but of the entire planet.

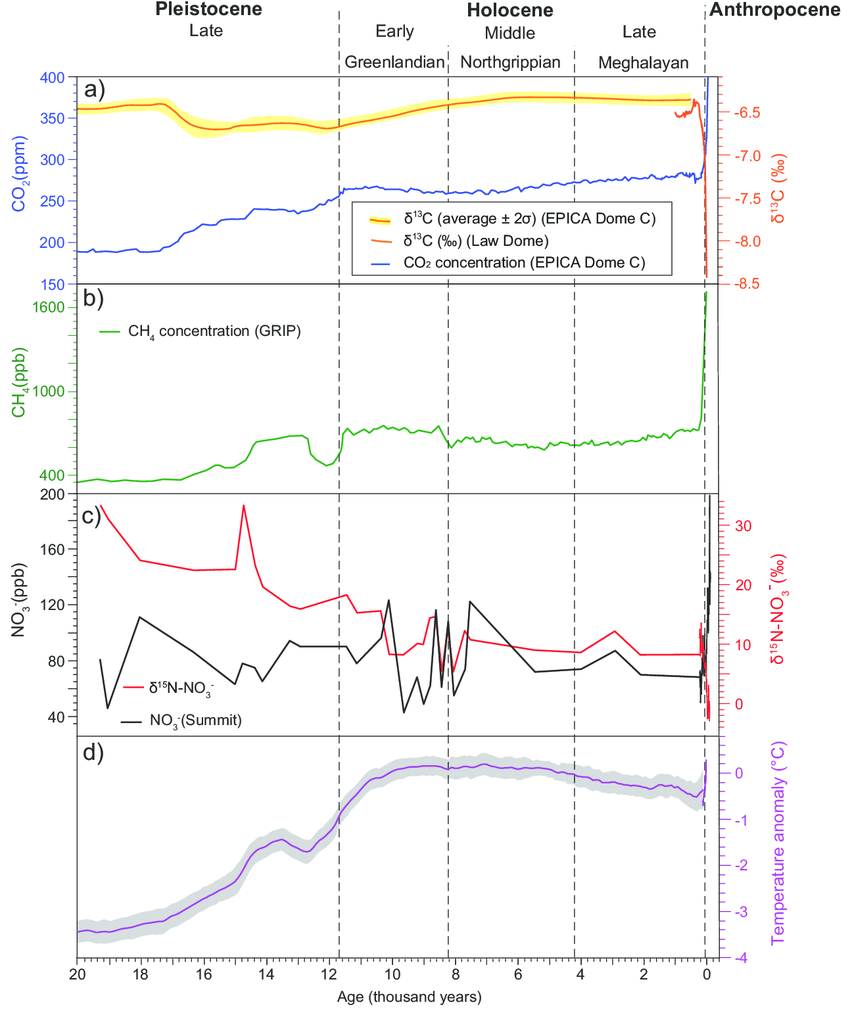

It is in particular the human activities beginning in the mid-twentieth century that have left a distinctive chemical and biological imprint in terrestrial and marine archives. What is becoming detectable and measurable in these geologic samples are planetary-wide effects of the “Great Acceleration,” the steep upswing and expansion of energy-intensive and industrial-scale socioeconomic activities around the globe since around 1950. In all kinds of natural deposits the Great Acceleration has left fine traces that signal the start of profound and—geologically speaking—highly sudden changes in the chemical composition of the air (i.e. the atmosphere), seas, lakes, and rivers (hydrosphere), sea ice and glaciers (cryosphere), and life itself (biosphere).

For the first time, chronostratigraphers are now faced with the challenging task of defining a geological epoch that is unprecedentedly recent. If the onset of the Anthropocene should indeed be nailed down to the mid-twentieth century, the AWG geologists themselves are inhabitants of the Anthropocene yet born of Holocene parents. As such they have the difficult task of assessing geological changes that have occurred shortly before or even during their lifetime. They have to conduct a geology of the present, attempting to trace out and structurally analyze a pattern which is still in the process of unfolding and which has no analogue in geological history.

At the same time, Anthropocene geology can work with an unparalleled level of certainty in measuring and dating its samples. Annual or even seasonal layerings in many of the environmental archives or the exact timestamp given by the test explosion of a thermonuclear bomb provide an exceptional clarity that other, more “floating” GSSP datings in the deeper time zones of the International Chronostratigraphic Chart naturally are lacking. Still, the crucial work for the geologists of the present lies in finding a technically and socially induced consensus about the right choice of markers, locations, and natural deposits that provide a globally synchronous time horizon. Simon Turner, current secretary of the AWG, describes the self-conception of chronostratigraphy in the familiar logic of scientific consensus seeking: Stratigraphic evidence is

obtained through millions of measurements (themselves the product of methods developed and used by consensus) and picked over by specialists dedicating lifetimes of work to understanding comparatively small amounts of Earth history. Even the most expensive and illustrious research is compared with previous work and subsequently tested. The more dramatic the conclusion of one piece of work, the more it acts like a magnet drawing in nonbelievers to question and test it.1

Far from constituting a hermetic field, stratigraphers openly deal with the uncertainty of their scientific object that is “rock time.” The deeper they go back in time, the higher the uncertainty. So they explicate uncertainty ranges (e.g. +/- 99 years for the Holocene GSSP) where an absolute dating is impossible. But beyond carefully hedging uncertainty, they also openly deal with the ambiguity of rock time itself. “The disjunctures between concepts and things”—time and rock—requires “work […] to suture them together,” writes Sophia Roosth in her ethnographic account of the GSSP endeavors undertaken by the stratigraphic subcommission responsible for dividing the Ediacaran Period (635 to 538.8 million years ago).2 Empirical scientists like stratigraphers have thus learned how to reach consensus over the causes and consequences of the informational value of their chosen scientific objects.

“Affixing time to place” (Roosth) means following an evidence-backed consensus mode in which periodization relies on the constant recalibration and testing of dating methods but also, in a way, of interpretation methods. This leads to an internally stabilizing, yet itself somewhat “floating” logic of evidence in which the Chronostratigraphic Chart does not represent an authentic record of Earth history “as it actually happened,” but a pragmatically-administered guide to divide the many befores and afters of geological evolution.

A pragmatic logic of evidence just like with the Holocene-Anthropocene boundary.

The legacy and latency of the Great Acceleration

The Anthropocene forensics practiced by the AWG, with their particular focus on the anthropogenic residues of the mid-twentieth century, is only concerned with a beginning. In profiling the decades around 1950—explicitly in comparison to the longer record that some of the cores hold— the AWG measures only the initial precursors of a dynamic which is now pushing the Earth System much further towards a fully-fledged Anthropocene. Whereas the AWG is mainly interested in the inflection point at which a certain anthropogenic marker—CO2, contaminants, black carbon, neobiota, microplastics, etc.—shows a prominent increase or decline, the actual impact on the global environment really stems from the cumulative amounts of these markers. With a few exceptions, like the steep plutonium signal already peaking at around 1962 (the famous “bomb spike”) and then slowly fading away, many of the diagrams that show the accumulation of markers in the environment still have comparatively low amplitudes during these early years. The actual dynamic of the impending changes in the Earth System at large remains somewhat latent in character.

But today the signal scope of many of these accumulated markers has grown multiple times over and now threatens to—soon—tip into uncharted territory: out-of-control climate change, the collapse of trophic food chains, global ecological and nuclear disaster, and a civilizational crisis of as yet unseen proportions. The dynamic that one can literally see in these diagrams is that of the “Great Acceleration”: the mid-twentieth century surge in momentum towards an all-encompassing change in socioeconomic and Earth system parameters.

The effects of all-encompassing industrialization, initially beginning in the Global North and later moving east and south, are no longer demonstrated only by changing environmental conditions in nearly all corners and spheres of the planet. They are increasingly felt by its inhabitants: a dramatic decline in species and genera, pollution on extensive scales, record-breaking extreme weather events, a steep rise in zoonotic diseases, and a rampant, planet-wide depletion of natural resources and human flourishing. This drift toward a systematic collapse of the climatic and ecological baselines of the Holocene and the impending uninhabitability of entire regions is the result of an increasing consolidation of technospheric systems in the wake of the surge in momentum that the Great Acceleration works to describe. It is one based on cheap fossil fuel energy, rapid technological innovation cycles, ever-increasing consumption, and a never-ending appropriation and colonization of land, water, air, and human labor. Looking back at previous decades, we can observe an escalation in the exponential logic of growth paradigms and the acceleration of highly industrialized and financialized societies. The Great Acceleration of circa 1950 is now a geological legacy, visible in sedimentary profiles; the future of its dynamic, however, is decisive for the survival of life on Earth as we know it.

The transition observed in the strata thus indicates a general discontinuity in relation to time: we are in a critical temporal zone in which the accelerating tempo of these developments can easily outrun any coordinated action, let alone uncoordinated ones. This out-of-control present threatens to affect the deep future in ways far beyond what used to be imaginable as human agency. One should be clear about the fact that the planet has, with the Great Acceleration, now only entered the very first or lowest stage of the Anthropocene Epoch. It is, by all kinds of scientific assessment, a highly disruptive transitional period of “global weirding” within which the established ecological, climatic, geochemical, and biological patterns of the Holocene are radically changing, if not threatened with complete collapse. In the long-term future, the system-wide shift now set in motion will likely lead to quite different metabolic conditions of our planet—a time when the actual Anthropocene Earth System will have tuned and stabilized in a new steady state. As Earth system science and various kinds of paleostudies show in extenso, the various subsystems of the Earth are prone to tipping-point behavior, where drastic shifts from their previous state are catalyzed when certain thresholds are reached. Critical components such as large-scale biomes like Amazonia, ocean currents, and cryospheric monuments like the once “eternal” ice shields on top of the Himalayas, on Greenland, or even in West Antarctica can be such tipping elements, whose shifts trigger further changes elsewhere on the planet in a domino effect.

Key geochemical trends for the Anthropocene from the Late Pleistocene to present, based on ice core records from Greenland, Antarctica, and instrumental data. Panels show prominent deflections of a) carbon dioxide concentrations and isotopic ratio of carbon-13 to carbon 12 (δ13C), b) methane concentration, and c) nitrous oxide concentration together with the nitrogen isotopic composition of nitrate (δ15N-NO3) at the proposed onset of the Anthropocene after a relatively stable period of the Holocene. Panel d) shows global temperature anomalies relative to the 1980–2004 mean. Source: Martin J. Head et al., “The Great Acceleration is real and provides a quantitative basis for the proposed Anthropocene Series/Epoch,” Episodes (2021)

Disparate presents

As a result, the contours of Anthropocene-age conflicts have now slowly entered political debates, legal disputes, and international regulatory frameworks. The threat of irreversibility and the narrowing timeframes for stepping on the brakes transform the question of justice in the Anthropocene into a question of critical temporalities. Lag times—if not the deliberate hindrance of ambitious actions—become questions of historical responsibility and unpaid debt between the generations born before and after the (geological) recognition of the Anthropocene. Long attempted but seldomly accomplished, the establishment of new and superordinate categories for social and environmental justice, for politics (on all spatial scales), and for law (of all domains) seem now to be slowly setting sail.

However, escaping the forces behind the Great Acceleration seems difficult or near-impossible when one looks at the unreversed upward trends of environmental degradation and global damage. The end of the Holocene seems easier to imagine than the end of capitalism. Running at a steady gait on the “treadmill of production,” the global economy is as dependent as nation states and their budgets on pushing forward the growth paradigm. The established or merely promised prosperity of modernity has penetrated deep into the social and fiscal psychology of nation-state structures. The exploitation of nature and the climate dumping of modern, extractive capitalism reach ever higher levels. The disruptive force of planetary changes has not been met with equally disruptive adaptation strategies, but rather with the persistence of old power structures, sluggish state apparatuses, and outdated regulatory frameworks for economic incentives and subsidies—a legal foundation that continues to be based upon individual property while ignoring the rights of nature. A grave disparity opens up between the highly dynamic changes to the planet and the impotent reactions of traditional institutions, inherited models of the political economy, and legal tools.

At the same time, the technospheric prosperity of industrialization and in particular the sweep of the Great Acceleration has also enabled an unprecedented emancipation from feudal political forms of rule and cultural dogmas. Behind the Anthropocene-elevated human as a planetary being stand formulas of energetic, material and political liberation (“carbon democracy” and “fossil freedom”) and the potentially limitless exchange and remixing of material things and ideational values. On the fertile ground of the Great Acceleration and the constant availability or overabundance of fossil fuels, crops, sugars and fats, construction materials and plastics, and not least the technical means of instantaneous communication, a cultural and identitary pluralism flourished that continues to profoundly shape our current societies.

Early-Stage Anthropocene: When pandemics and winter wildfires converge. Photo by Wendy Cardona, © All rights reserved Wendy Cardona

Now that our attention must be directed at the possible reactions and social demands that align with the dynamic nature of the Anthropocene signals, it seems highly questionable that we, as human communities, are structurally capable of weaving exactly the network that will lead us from the evidence to a solution, i.e. to not only the technological but also social innovations that will help to at least decelerate the terrestrial crisis. Do we have a clear enough understanding of the legacy of the Great Acceleration of the mid-twentieth century, so meticulously studied by the AWG, to actually halt this ominous development? Can we keep the no-longer-latent dynamics of the mid-twenty-first century at bay?

The Anthropocene noise

Indeed, the epochal rupture observed in the sediments and ice cores demands an equal discontinuity in our ways of living and acting. But while the Earth now speaks to all of us, geoscientists and vulnerable inhabitants alike, ever more clearly and distinctly, our responses are disparate and diffuse. Shaped and thwarted by the institutional, economic, and psychic patterns of world appropriation—whether in the west or the east, the north or the south—the customary technological and emancipatory fervor of modernity has drifted into entropic agony. It’s not just outright denial that counters meaningful discourse and action. It is the sugary syrup of everything-goes and everything-is-right cultural logics that block all final resorts to change course. Amid the cascading planetary crisis portended by the collapse of the relatively regular pattern of the Holocene, a babble of voices reigns, exploiting the self-replicating multiplicity of often-times contradictory cultural norms and sociotechnical practices, alternative facts, ephemeral concepts, and inconsequential lip service, a favorite of governments and corporations. The scientific consensus, however provisional, is not matched by any social equivalent. Whereas signals float in the former, they cancel each other out in the latter.

“It’s the obsession with generating noise, regardless of signal,“ writes a frustrated George Monbiot in an op-ed in The Guardian, deploring the maddening failures of the media to cover the existential threat of climate and biosphere breakdown amongst the never-ending stream of trivia and spectacles—“a manufactured indifference.”3 But more than just the inherently flawed logics of mass media, or even the inertness and psychic aversion of saturated boomers (“Generation Great Acceleration”) to give up on their gas-guzzling and life-killing lifestyles, it seems that a more systemic, deeply ingrained economic and cultural modus operandi is at play that creates societal insensitivity to the signal.

A good lead on the nature of this systemic failure comes from literary scholar and astute analyst of contemporary political economy Joseph Vogl. In his book Kapital und Ressentiment. Eine kurze Theorie der Gegenwart (roughly translated: “Capital and Resentment: A Short Treatise on the Present”) he describes the ways in which social animosity is both a product and a resource for the economic exploitation of information.4 The rise of platform capitalism is a result of the technological and commercial fusion— over decades—of the information economy with the financial industry. Polarization and the combustive ventilation of affects are thus an integral part of a business model that is now culturally and economically dominant.

Another clue to account for the incompatibility of the Anthropocene crisis with contemporary socioeconomic incentive schemes comes from an intriguing observation by media and design theorist Orit Halpern, which she terms the logic of perpetual prototyping and demoing. Halpern argues that today’s forms of value production—in general but even more so in the face of Anthropocene risks—are guided by keeping everything in the operational space of the provisional. Real estate developers, financial markets, and even consumers are caught up in an infinite cycle of speculation and future bets in which every design (of a product, material or virtual, a smart city, a financial asset) is just yet another experimental prototype in a self-referential system—one that neither takes any external consequences into account nor is willingly-designed to bear any consequences at all. “The design logic of repetitive demoing,” she writes,

facilitates the constant management and negotiation of risks through derivation (from an imagined origin) in a manner that avoids ever having to finally discover the impact of respective events—whether weather, economic, or security—on the world. Every version, demo, or prototype allows us to commence with failing to encounter the planet, or the violences of security, by labeling it “a never truly completed effort” from which the next version may be derived.5

It is worth thinking about an expansion of this insightful concept to the arenas of politics and governance, and even to cultural norms. Today, when the disruptions of local and global ecological patterns encounter the fragmented field of the social—itself highly dynamic, complex, and prone to tipping-point behavior—any reaction is guided by a late-capitalist culture dominated by short-term appropriation or continual re-assembly of social norms, cultural codes, political opinions, and temporal identities.

A present where the modes of evidence and of experiment clash with each other

Distinct signals of the present, which the AWG attempts to disentangle, have a hard time in our prototyping present, where ideal, as well as material values always have a provisional character. Subordinated to a paradigm of continual testing and rejecting, values are found and discarded without the prospect of a sustainable realization or usage. Whereas scientific evidence has to consciously deal with the floating inherent in their pragmatically chosen objects, the ultimate goal of contemporary economic value extraction is the floating itself. Fluctuation is where profit and cultural distinction unfolds. Late capitalism does not establish, fix, or stabilize anything whatsoever, but just creates wealth from accelerating, self-referential change.

The accurately isolated signals of Anthropocene stratigraphy therefore encounter the raging stasis of continually changing economic/cultural/ideological/technical experiments, in which outpacing innovation cycles and swapping cultural codes have become the motor for value creation and profit. While the AWG searches for chronological evidence, the modes of capitalist, as well as cultural innovation cycles still bask in a dogma of “time-forgotten” experiments borne from the modern gesture of a human-centered appropriation of the world.

It might, therefore, not be a coincidence that against the background of the Anthropocene’s mounting civilizational turbulences, the loss of a pattern and the proliferation of cultural and economic profit models generates an emotional, communicative, and material overburdening. This social vertigo of world alienation joins the structural exclusion from the world, passed down by centuries of social and racial hierarchicalization and domination. This not only results in individual feelings of dysfunction and impotence, but above all in dysfunctional and impotent politics. The crisis itself becomes an empirical laboratory in which modern collective systems, including those of Western democracies, must withstand their crash test in the relentless fire of the multiple crises we now call the Anthropocene.

Christoph Rosol heads the research cluster Anthropocene Formations at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science and works as a researcher and curator at Haus der Kulturen der Welt.

Please cite as: Rosol, C (2022) When the Signal Disappears in the Noise. Geology of a Floating Present. In: Rosol C and Rispoli G (eds) Anthropogenic Markers: Stratigraphy and Context, Anthropocene Curriculum. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. DOI: 10.58049/CRTG-AM52