The Terrain of the Former VEB Elektrokohle Lichtenberg

The site

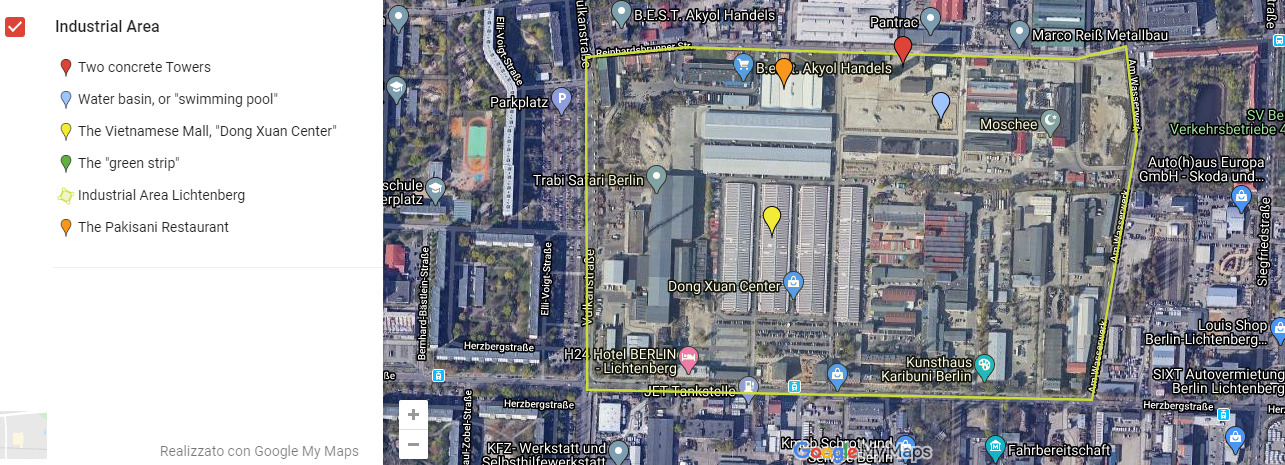

Currently the site is divided into four distinct areas that are easy to identify on the aerial view map (Image 1): one area is still industrial and used by a factory; another is a restaurant area run by a Pakistani entrepreneur; the third and largest area on the site is the so-called “Dong Xuan Center,” a huge conglomerate of Vietnamese shops and restaurants; and finally there is a “green strip,” comprising land that seems to be considered not too contaminated and is grass-covered with a few trees. This strip divides the whole site from the surrounding area before the horizon shifts into the prefabricated slabs of GDR mass housing.

In the well-established “Dong Xuan Center,” several workshops found their home, now comprising the “largest Asian market in Berlin.” Close by, the building still owned by “Pantrac,” the company that bought the site from Treuhand after the reunification of Germany, produces carbon and graphite objects as it has done since 1997. The main VEB factory buildings were demolished, but the two giant concrete towers that remain were preserved simply because it was too expensive to dismantle them. All the steel components of the former factory, however, were sold to China.

The soil on the site is highly contaminated; therefore, the whole surface has been paved over with concrete. In some areas, the concrete seems to be unstable. Soil pollution apparently has not affected the local perception of the danger the contamination may pose, and economic activities continue to flourish. The entire area around the two concrete towers is currently owned by a Pakistani entrepreneur who established part of his business empire alongside a Tandoori restaurant on the site. Although his permit only covers the running of the restaurant, he runs it as a canteen to serve all the on-site workshops. The loose regulatory framework regarding land exploitation is due to the German political transition in the 1990s, which created the preconditions for the present lack of clarity with respect to the legal situation of the many businesses on the site.

Image 1: Map view of the Industrial Area Lichtenberg Image source: Google Maps

In order to sell land parcels belonging to the site, the owner was obliged to construct a reservoir to act in accordance with fire-safety regulations. The giant pool subsequently constructed is affectionately and somewhat ironically known to locals as the “swimming pool” (see image below). Some of the soil removed for the realization of the reservoir was used to construct a small hill on which grass seed has been grown; the vision is to one day have goats grazing on it. The remaining soil became the basis of a huge platform of around 60 cm high. This giant sarcophagus, the size of a tennis court, finally furnished with a number of street lamps, may become an ice-skating rink in the future.

During several visits to the Lichtenberg site prior to the Campus 2014, we explored the definitions of places and spaces that the people working in, living in, and using the space for diverse activities currently use. Naming a spot of land is a well recognized human trait that frequently refers to people’s perception of its actuality, what it is destined to become, or the owner. In the case of the Lichtenberg site, the names people know it by indicate an element of wishful thinking, or define a would-be hypothesis that surely cannot be understood in a literal sense. In particular, considering the highly polluted, ugly, rather than inviting nature of the site’s features, the (nick)names attributed to places on it represent a project, and express an idea of development and change. People speak of a possible future for the place in clearer and shorter words than a detailed map. Both the “swimming pool” and the “ice-skating rink” refer to leisure and entertainment, although a somewhat standardized conception. The “hill” and the idea that one day goats might be left free to graze on it, as a way of nurturing it, speak to people’s desire to “go green,” a means of inscribing value into a heavily exploited area of land where clearly grass has near zero value.

The people

Berlin hosts a large community of Vietnamese people, many of whom arrived during the 1970s thanks to the workers’ exchange programs established between the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the former GDR. The Vietnamese workers who were selected for special training programs among the local elites in East Germany did not plan to emigrate permanently to Europe, and they expected to return to Vietnam after the five-year training concluded. No project or program was dedicated to integrate the community in East Germany; almost no one learnt German, and, generally, contact with German society was confined to a minimum.

A completely different situation can be observed with the South Vietnamese community that emigrated to West Germany. Opponents of the Vietnamese socialist regime escaped from the country without any real hope of ever returning, and special facilitating programs established to promote integration were largely successful. The detailed study of these processes goes beyond the scope of the current case study, but, in outline, the relevant data suggests that to this day the split in the Vietnamese community in Germany is apparent, reflecting the different emigration processes, reasons for emigrating, and political views—in Vietnam as well as in Berlin.

In East Berlin, the Vietnamese workers were mainly employed at VEB Elektrokohle. After the factory closed, however, only a small number accepted some financial support to return to Vietnam. The majority remained in Germany illegally, experiencing several phases of isolation and economic crisis. These factors in all likelihood resulted in their determination both to provide a livelihood and to meet all primary local needs within the same community. This large migrant community, which on the one hand has a longstanding presence in Berlin, and on the other hand lives quite separated from the rest of society, is a base for the emergence of a sort of “enclave system” with a robust economic and cultural autonomy.