The Tennessee Valley Authority goes Japan: A river’s way into the Anthropocene

Damming is one of the most visible and consequential human interventions affecting rivers and is seen as an indicator of the Anthropocene. Using dams as a central tool in its practice of systematized river management, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) heavily promoted this form of engineering as a means to achieve economic prosperity in the 1930s and 1940s, providing a blueprint for similar interventions around the world. Mariko Jacoby looks at how Japan became an early adopter of TVA-style river engineering and dam construction.

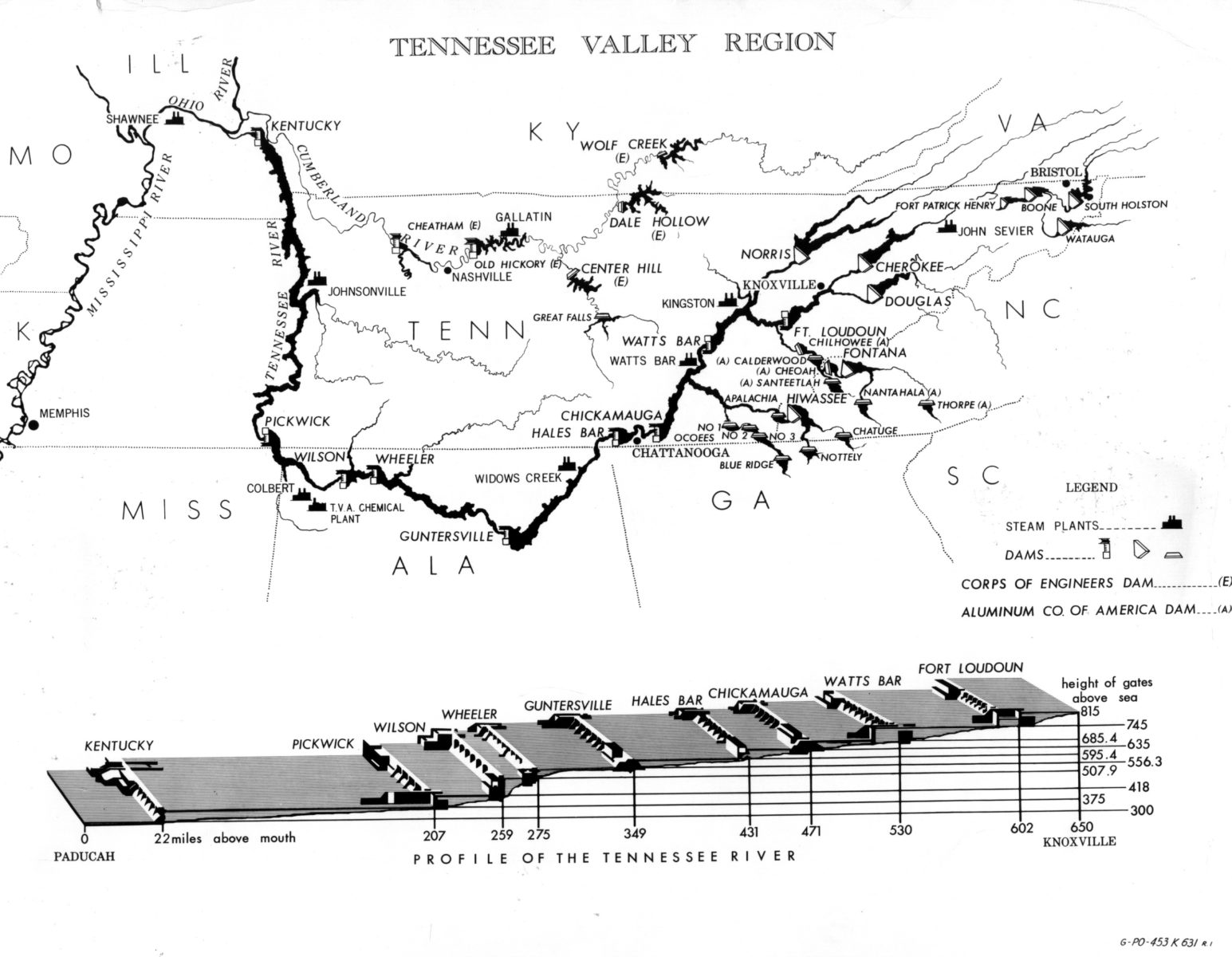

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is mostly known as a power supplier and as an experiment in regional development. It was founded in 1933 to fight the most devastating effects of the Great Depression and the longer-term problem of “underdevelopment” in the South. It provided thousands of much needed jobs for the region, boosting agricultural outputs, and offering people a more modern way of life that included electronic lightning and fridges. Initiatives ranged from electric power plant construction, fertilizer production, and afforestation to fight against erosion, but at its core lay a concept about how to manage and use a river: A system of dams turned the river into a series of reservoirs which turned surplus water that risked causing floods in the watershed downstream, which includes the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, into resources that could be used for irrigation and hydroelectric power. The Tennessee, which hitherto had flooded almost 11,000 square miles a year (or 28,000 square kilometers, roughly a quarter of the region), was equipped with seven dams between 1933 and 1944, while nine dams were built on its tributaries and an additional five dams were acquired from other companies. In total, these created fourteen million acre-feet (over 17 cubic kilometers) of flood storage. In 1944, the TVA produced 83 percent of its total electric production by hydroelectric plants (8,424,935,000 kilowatt hours), while serving 550,000 private and industrial consumers.

The TVA was far from the first project to use dams for the purpose of producing electricity and boosting agricultural output, but it became a successful blueprint for river management all over the world.

As a result, the construction of large dams has accelerated since the 1950s. Dams, which have a considerable impact on river ecosystems, are an obvious example of human interference in natural processes, and are rightfully seen as an indicator of the Anthropocene.

Why did the TVA have such an impact on the world’s rivers? A possible answer might be found by looking at Japan, which was an early and enthusiastic adopter of the TVA approach.

Prewar glances over the Pacific: Dams for the Empire

In the beginning of the 1930s, the construction of dams became an increasingly pressing issue for Japan, which was plagued by economic problems and disasters. The 1930s saw typhoon and flood disasters, crop failure, and the Great Depression caused famines in northeastern Japan, while resources were also needed to sustain its growing empire. To obtain the knowledge to build dams, the Japanese looked to the US, a nation that had been successful at building concrete high dams: The larger scale enabled the installation of reservoirs to retain large amounts of water and even prevent floods. Several Japanese engineers visited the US to learn from the country’s dam construction, and Japanese officials studied the organizational structure of the TVA for inspiration. When the Japanese Home Ministry proclaimed a new concept of river management in 1935, they cited the TVA as a successful example of a centrally managed hydroelectric dam system to justify their dam-heavy program.

The prewar project most influenced by the TVA concept was a development program for northeastern Japan, which had suffered tremendously from the Great Depression. Cold summers had caused crop failures in this region in 1932, 1934, and 1935, with devastating effects. Reports were made of farmers in debt, malnourished children, and families selling their daughters to brothels. Beginning in 1936, a comprehensive development plan was mapped out to boost this devastated region by undertaking industrial production of fertilizers and resource extraction. In addition, the construction of five hydroelectric dams on the Kitakami River was decided upon in 1938. As it was, relief and development of the disaster-stricken area was turned into wartime production for the Japanese Empire.

Likewise, the rivers in the newly subjugated puppet state of Manchuria were used to produce electricity for the Japanese Empire during the war. Japan had established the puppet régime of Manchukuo in 1932. This had caused an intense backlash against the Japanese Empire, which in turn walked out of the League of Nations. When the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, electricity companies in Manchukuo began to build large-scale dams. The planned Sui-hō Dam was the largest dam in East Asia. To cope with the technical issues, they sent engineer Kuga Tokuhei to the US. At that point, apparently, the growing tensions between the countries were not yet an issue. Kuga was shown details and plans of the respective dam constructions, including the TVA, and bought machinery from US companies. Kuga’s accounts became the basis for prewar Japanese dam technology.

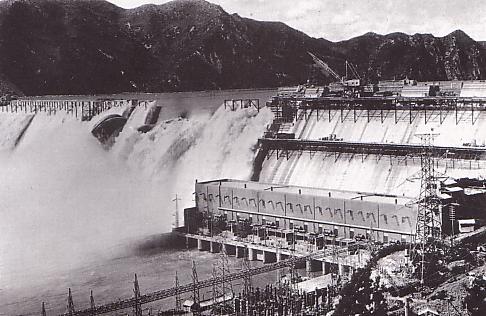

Sui-ho Dam (now Supung Dam) under construction, 1942, Source: Wikipedia

Dam construction was intensified in the late 1930s by the need to power Japanese wartime production. Ironically, the TVA, the role model, followed a similar trajectory, reaching the peak of its hydroelectric productivity in the war years. For the Japanese Empire however, the dam building sites had to be halted in the last war years due to serious material shortages. Curiously, Japanese interest in the TVA was kept alive even during the Pacific War: Aki Kōichi, who would become a leading figure in promoting the TVA model in the postwar period, published a book on water control in 1943 which gives a detailed account of the TVA’s development.

The American occupation in Japan and the TVA craze

After the Second World War, Japan came under Allied control, which effectively meant US occupation. While the emperor was kept in place, it was the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces (SCAP) that gave orders to the Japanese government until the end of the occupation in 1952. Japan was stripped of all its colonies and reduced back to its main islands. Deprived of the resources from the colonies, its major cities destroyed, and millions of its citizens killed during the war, Japan faced serious food shortages. For the US, which had arrived in Japan with an army of experts to reeducate and reorganize Japan into a democratic country and an ally against the communist threat, one of the first tasks was to tackle the material and resource shortages. American geographer Edward J. Ackerman, who was tasked with reorganizing Japan’s resource acquisition, noted that while Japan lacked fossil energy resources, it had an abundance of falling water: large amounts of rainfall and many rivers in a steep topography made it ideal for the use of hydroelectric dams. Subsequently, Ackerman created a Resources Council in 1948 in which American and Japanese experts worked along each other to solve Japan’s resource problems.

This Resources Council became a place for vivid discussion and knowledge exchange. There, Ackerman, who was a proponent of the New Deal and the TVA ideas (of which he became vice general director after his return from Japan in 1952), promoted the TVA concept to the Japanese experts, who enthusiastically embraced it as a solution for Japan’s resource and flood problems. Since the end of the war, Japan had been struck by severe typhoons almost annually. These caused serious floods with hundreds of deaths and thousands of destroyed homes. The damage was blamed on the lack of maintenance of the rivers during the war and the wartime destruction of the environment. The TVA concept would turn Japan’s rivers from flood menaces into resource carriers for irrigation and electricity instead, thus killing two birds with one stone.

A lively knowledge exchange between Japanese government officials and the TVA ensued: David E. Lilienthal’s 1944 TVA promotion book TVA: Democracy on the March was translated into Japanese in 1949, and several Japanese delegations visited the TVA, interested in the mixture of the TVA’s concrete as well as in the underlying organizational structures. Lilienthal himself was received enthusiastically when he visited Japan in 1951. The TVA was also brought to the Japanese public, promoted as the ideal solution for the typhoon flood problem, making its way into newspapers, magazines, and children’s books. The abbreviation “TVA” became somewhat of a buzzword in postwar Japan, used as a shorthand for the ideal form of flood control. The resumed construction on the Kitakami River was dubbed the “KVA” to honor its forbear.

Proponents of the TVA have emerged, spread across the breadth of society, and permeated into every stratum of people. More and more people have taken an interest in it . . . If there is a typhoon or heavy rain, the TVA’s name is likely to be mentioned when a flood occurs. The TVA has a relationship with afforestation and river improvement policy that is impossible to sever, and as though the work of some genie, it has crowded the pages of newspapers and magazines. What is more, the radio has taken up . . . the TVA, and in certain situations, the TVA . . . is even a “conversation starter.” At one point . . . it seemed the TVA’s name never failed to appear on the pages of daily newspapers.1

A small number of geologists warned against dams, pointing out that they would disrupt the sedimental flow and claiming other forms of traditional flood control (such as embankments that allowed overflow) would be more beneficial. Ignoring such concerns, the Japanese government issued the National Planning Law in 1950, subjected 16 major rivers to development, and continued to pursue the TVA path after Japan’s release into independence in 1952. However, this form of comprehensive planning had significantly departed from the aim of regional development: It was reduced to a coordinated way of river management, designed to benefit the metropolitan regions. Much dam construction, most famously the Shimouke Dam in southwest Japan, met fierce local resistance. In the majority of cases, resistance was brought down by government intervention. With the following period of high industrial growth in Japan, a golden age of dam construction began: Japan’s dams were fueling the industrial production and ensuring consumer comfort. Today, there are over 3,000 registered dams in Japan, which makes it the world’s fourth most dammed country, only surpassed by the US, China, and India.

Globalizing the rivers’ way into the Anthropocene

The TVA was far from the only facility to use high dams, but it was tremendously successful in selling its river management concept as a recipe for economic prosperity in countless publications. Its basic principle was to build a row of dams that would tame wild and disastrous rivers into calm bodies of water which could be used as resources for irrigation and electricity. This would change underdeveloped regions into rich and prosperous landscapes. This principle was precisely what fascinated the Japanese, regardless of ideology: In the 1930s, they attempted to transform Manchuria and a famine-stricken remote area in northeastern Japan into industrial regions to supply the war in East Asia. After the war, the TVA became a vision of democratization and a blueprint for how to rebuild the war-torn environment to meet the growing resource demands.

The TVA, in its first decades of existence, was a successful figurehead to showcase the attractiveness of the American model and its achievements in modernity, which representatives of many countries flocked to see. Japan offered the first proof for the successful export of US development policy overseas, which turned the once violent and fascist Imperial Japan into a peaceful and democratic economic powerhouse, and a faithful ally to the US. Thus the TVA, despite the domestic controversies it provoked for its government involvement and lack of economic competition, became a blueprint for US-led regional development all over the postwar world. Investments, infrastructure projects, and expert engineers, it seemed, were all that was necessary to turn “underdeveloped” areas into prosperous landscapes, with the purpose being to tie them to the US and ensure its hegemonic status.

The worldwide boom in dam construction, however, was not without ecological cost. Accordingly, dams have come under increasing scrutiny since the 1970s. The concept of turning rivers into resource reservoirs for industrial and agriculture production travelled around the world without regard to the rivers as ecological habitats. Rivers were fundamentally altered to serve human convenience, transforming countless rivers into engineered systems. Dams change not only the ecology, but also the geology of rivers: Sedimentation is trapped, and the load is reduced. This results in sediment scarcity and coastal erosion. This in turn becomes a danger in the age of sea level rise. Dams are thus a glaring example of how humans have become geological agents, tampering with one of geology’s basic dynamics: the sedimentation process. Systematic damming, as promoted by the TVA, is a common trajectory of a river of the Anthropocene. The Tennessee, as much as the Mississippi, to which it is a tributary, is not only a river symbolizing the Anthropocene, it also carries the most important promoter of a river’s way into the Anthropocene.