The Multispecies World of Technology

In Conversation with Elaine Gan and Betina Stoetzer

Elaine Gan, Bettina Stoetzer, and Anna Tsing led “Feral Technologies: Making and Unmaking Multispecies DUMP!,” a two-day seminar that took place during Anthropocene Campus 2016: The Technosphere Issue. Tsing and Gan work together in Aarhus University’s Research on the Anthropocene (AURA) department in Denmark, exploring the potential of ferality and unintended landscape design. Parallel to her interest, and in preparation for her forthcoming book Ruderal City: Ecologies of migration and urban life in Berlin, Bettina Stoetzer has been researching ruderal ecologies, examining urban life forms that emerge in inhospitable spaces. In the following conversation, Gan and Stoetzer discuss the underlying principles of their seminar, including ferality, ruderality, and how those terms expand our concept of technology.

Caroline Picard: What are some key concepts from your seminar?

Elaine Gan: With the work of Anna Tsing and AURA, we are trying to think about what ferality is. That is one key concept; the other relates to: What is technology? What is the technosphere? How do we think about the disconnections that come about because of human-made infrastructures? Also not to forget that technologies come out of multispecies life experience; machines do not grow on their own, but emerge out of different interactions with the environment. The second term we are trying to unpack: What is a technology? What prosthetics do human beings make in response to other things going on in the world? As an artist and also a researcher, I am also trying to play with making and unmaking, asking not just how we make things, but how do we make them critically? And how do we make things in order to unmake long lineages of great violence? How do we make better? The forest term is “dumps.” It is a figurate conceptual device, which we use to think about landscapes created in the Anthropocene. This is where Bettina Stoetzer’s work on rubble and ruderal ecologies enters.

Bettina Stoetzer: “Ruderal” is a botanical term that comes from rudus, which is Latin, meaning rubble. It refers to organisms that spontaneously grow in “disturbed environments” usually considered to be hostile to life—alongside railway tracks, for instance, or roads, waste-disposal areas, or literally rubble. I draw on this term and develop it as a conceptual device for thinking about landscapes in the Anthropocene in my forthcoming book, Ruderal City: Ecologies of migration and urban life in Berlin. The interesting thing about ruderals is that they are neither really wild nor domesticated; they are non-native species and they dwell in the gaps of urban infrastructures like invisible hitchhikers. If we follow the history of ruderals, a “ruderal city” emerges within which nature is not “out there”—as a site to be managed or incorporated into anthropogenic urban landscapes via technology and infrastructure—but is rather an integral and unwieldy part of the city.

CP: I understand that you all went to a park?

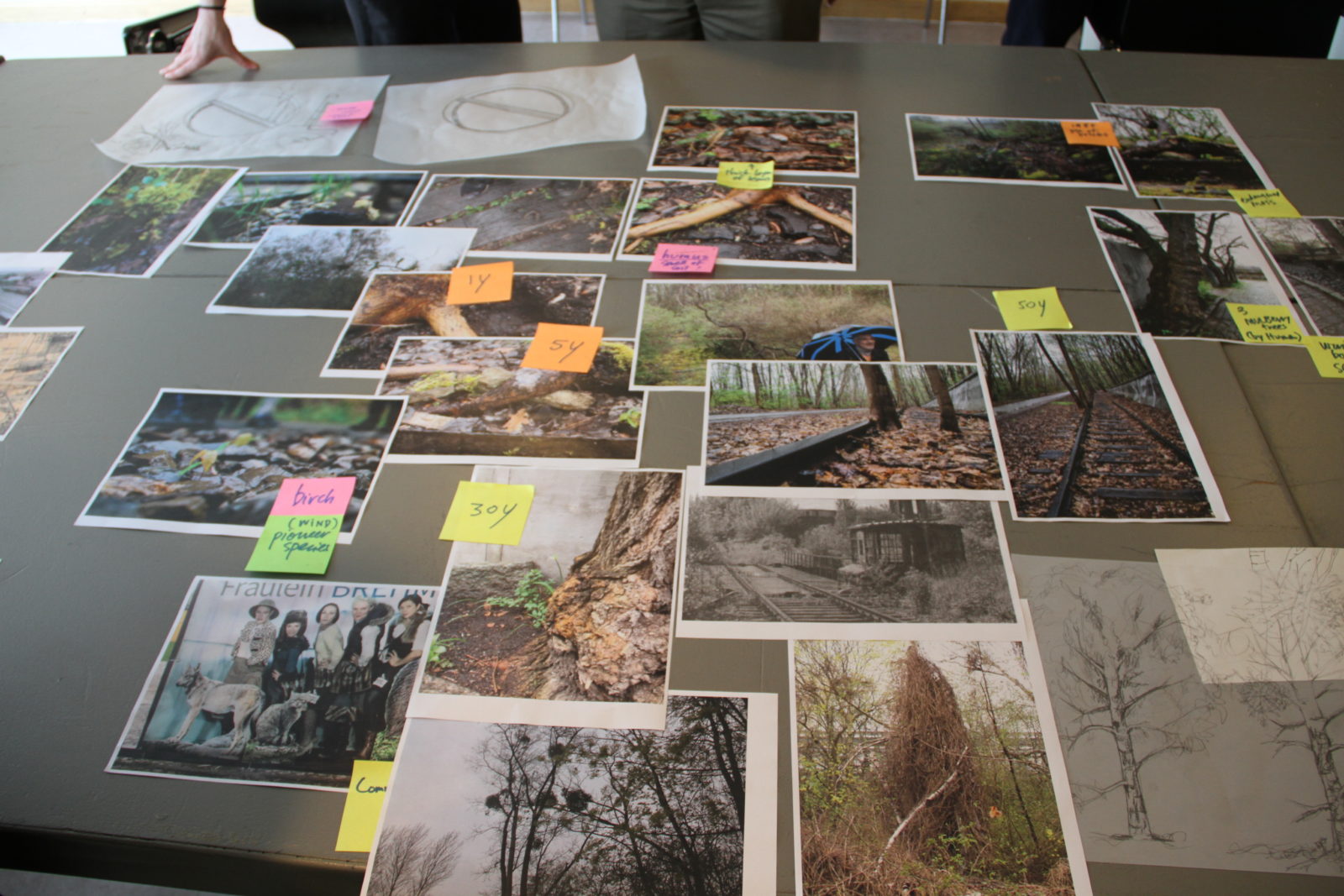

BS: Yes, rather than being distanced observers in the classroom, we wanted to ground our discussion in a particular site, to let our encounters with the site’s materiality—its plants, the crumbling infrastructure, alongside its smells and sounds—guide our discussion. The so-called Schöneberger Südgelände seemed like the perfect spot. It was an abandoned switchyard for trains during Berlin’s division after the Second World War, and then became a nature park in 1999. The site is full of ruderal ecologies and feral fauna and flora. We invited seminar participants to explore the entangled histories, encounters, and ecologies that shaped the yard’s landscape. Encouraging them to experiment with their own documentary practices, we asked them to think about the kinds of story that a place like this could generate.

EG: We’d been thinking through a short story that Ursula Le Guin wrote, her “carrier bag theory of fiction.” The part I really like relates to how we tell new kinds of stories. In our seminar, we use a sense of play among different people coming together for a brief period of time: What stories can they tell inspired by a walk? We went to the park in the middle of a thunderstorm, so we could have created what Ursula Le Guin calls “scullery stories”— life stories that are open-ended. Stories about fungi, for example, which might hitch a ride on a leaf that has fallen from a tree, that might be decomposing, but nonetheless that fungi is starting a whole new world.

CP: Doesn’t Shock and Awe: War on words (2004)—the book you co-edited, Bettina—look at how words build worlds?

BS: Yes, Shock and Awe is a collection of essays and vignettes that provides something like a dictionary of the world in the post-9/11 George W. Bush era. We were interested in exploring the political life of words. For example, the word democracy, or freedom, or terrorist: the different entries in the book explore how politics and language are deeply intertwined, how words change their meaning and have the ability to alter our experience of everyday life in a world that is marked by imperialism and global war, hence the subtitle War on words. It also illustrates how words can be hijacked, and reclaimed to enliven a different sense of the political. In other words, the question at stake there was also: What are the feral lives of words and how can we tell alternative kinds of stories about the political?

CP: I almost want to tie that into the idea of unintended design in landscapes at AURA.

EG: Sure. AURA is housed at Aarhus University, Denmark, within the Department of Anthropology, and grows out of a five-year Niels Bohr professorship awarded to Anna Tsing. It looks at unintended design in landscapes, or the idea that landscapes materialize because of a whole range of historical trajectories. They do not come out of human mastery or planning—this notion belongs with human exceptionalism, actually.

BS: Again, this is where the idea of ruderal ecologies comes in. What is interesting about Berlin’s postwar ruderal plants and their larger ecologies is that they are the outcome of nationalism, war, environmental destruction, and trade. So there are all kinds of layers of the city’s histories, the political and economic conditions that have materialized in the actual ecology and flora of the city. On top of that we have making, unmaking, and, above all, we have growing. And growth, in the ecological sense, is always dependent on other factors and unanticipated variables—it’s not a uni-directional, one-man, fully controlled enterprise. Often there is unwanted growth and mutation.

CP: How does all this tie back into technology?

BS: By stressing the feral and ruderal, we ask: What happens if we imagine technology not only in terms of human forms of externalization, but also in terms of internalization and unexpected proliferation and growth? This is why Le Guin and feminist reimaginings of technology matter: we want to get away from thinking of technology as the story of human omnipotence. Rather, we want technology to be thought of as the science of craft, an open-ended process that is always embedded in a particular locale and in multispecies worlds.

EG: Human intention, in a way, is an illusion, so our approach is coming out of an anarchist politics. It is an anarchist project to suggest we decenter the role of humans in the landscape. This is not to say humans are not part of the picture, but what if human beings are only one species among many? What if we expand the notion of culture and nature and say that there are more than human socialities? What are those socialities? How do we combine multiple disciplines to find out? What are these new kinds of landscapes out there, which don’t arise from human mastery or human technologies, but rather emerge from the messes that human beings have made and that particular individuals have made?

CP: You recently curated a related exhibition, didn’t you, Elaine?

EG: Actually, I’m the art director for AURA, which means I get to play with lots of interesting experiments, and while I was in Denmark I proposed an art and science exhibition called “DUMP! Multispecies Making and Unmaking” at Kunsthal Aarhus. I co-curated the show with Sarah Lookofsky and Steven Lam. “DUMP!” has a dialectical structure to it: on the one hand, we wanted to think about industrial ruin or the ruins of capitalism and specifically neoliberalism; on the other, we wanted to think about the multispecies life that emerges, and how that might trouble this notion of a hero. A human hero that attempts to make the world. We brought together about nineteen different artists, scientists, organisms, including self-healing concrete embedded with bacteria from researchers at Delft University. We also included mycorrhizal fungi, which is based on the collaborative research between Anna Tsing, the anthropologist, and Henning Knudsen, the natural historian. In essence, the show was trying to explore the positive aspects of decomposition; without decomposing, we’d have a world stacked with rubbish, but because of other species, wood breaks down. We also featured Amy Balkin’s ongoing project, Archive of Sinking and Melting, where she asks anyone who happens to be in a landscape that will disappear as a result of climate change to send in an artifact from there, creating an archive of future disappearances. There is a candy wrapper from Nepal, a discarded patch, a pair of discarded ice shoes, for example, from somewhere else. It is a feminist exhibition, at least in the sense that we wanted people to look at lives that make and unmake the world.

BS: I see many overlaps here: in my book, in a way, I’m offering a “ruderal tour” of Berlin. This tour does not follow the neat lines of neighborhoods, communities, urban infrastructures, or institutions, but looks at what emerges in the cracks alongside or between them. What I find fascinating are the unexpected neighbors, the things that at first glance may not appear to have anything in common. What happens if we juxtapose different inhabitants of the city, for example? And this comes out of my fieldwork: How do Turkish barbecuers, rubble plants, German environmentalists, East German bunker enthusiasts, sunflower seeds, and East African refugees inhabit the city and connect or disconnect with one another in different ways? What are the material traces of various kinds of social interaction in the city, among both humans and nonhumans? I am excited about exploration and gathering—like Le Guin’s story: you do not act out the god trick of observation, but instead gather, and allow yourself to get a little lost while collecting things you find along the way. If we look closely, cities—and this is also true for the technosphere—are much more interesting and odder than we might think.

CP: What is it like to work in such multidisciplinary modes? What is the difference between an artist and curator, for instance?

EG: Yes, this is the interdisciplinary question, which is always very hard to answer.

BS: I believe it is important to not get tied down to the dividing lines between art, curation, creative writing, and scholarly analysis. We reassemble things as critics, we connect the dots and create new lines of inquiry, new modes of seeing and inhabiting the world. I also believe that it is essential to redefine existing standards of what constitutes “scholarly analysis” and rigor today. In the case of the ruderals that I mentioned earlier, and I think this is also true for all things feral, the interesting thing is that you often don’t find them within the usual rules of (scholarly) structured observation—but rather, since they emerge by chance, you don’t know exactly where to find them. The kinds of world we inhabit today—crowded, with unexpected toxins, and invisible forms of violence—therefore require us to sharpen our peripheral vision or to practice what the artist Lois Weinberger has called “precise modes of inattention”: you see feral beings as you pass through a place, on the way to somewhere else. We need to take these kinds of risks (of not knowing in advance where to look) and to engage with multiple things at once in order to understand the complexities of what is going on in the Anthropocene.

EG: It parallels my work with rice, maybe. At the moment I am researching six different types of rice, not to put rice at the center of each study, but to actually say, “What happens if we follow the world by looking for a specific type of rice?” The six different studies use rice as an entry point and then examine different companion species gathered around rice. What are these assemblages that come together because this kind of rice has to be cultivated and has to live in the world in a certain way? It is assuming that the local is always an already-global. It is also always an already-historical, as well as an emergent narrative. By looking at rice, you start to make the effort to take a more expansive view of spaces and times.

CP: That makes me think about something you said earlier, Elaine, how you can look at technology as a kind of responsive prosthetic—similar to when a human identifies a problem, say, the limits of an average person’s encyclopaedic knowledge, and so the internet or Wikipedia emerges to expand that limit. I guess I wonder if in the same way one could look at social and political policy as a kind of technology too?

BS: Yes, absolutely, that’s a great thought. That’s also what I gestured at earlier when I said it is interesting to look at what emerges alongside institutions, infrastructures, and formal economies. It’s the same with policymaking: there is always an excess and unexpected outcomes that are not anticipated and cannot be fully governed. In the context of migration, we see this happening now in Europe and across the world: the scrambling to control national borders against so-called “floods” of refugees and migrants (note that refugees in the much-debated refugee crisis in Germany right now are likened to waves and tsunamis, and thus to natural disasters). And yet there is an excess of people’s resilience, their desire to survive and make things livable. That is also the Anthropocene.

CP: Do you all think the Anthropocene is a fad? Of course, I believe in the seriousness of our ecological times, but I also notice a high amount of fervor around the word. What is the world-building around that word?

BS: I think the Anthropocene is a tricky term—it is both good to think with, but it also has its limits. It gets humans to reflect on their own accountability and pushes one to reflect on how we have gotten ourselves in this mess. We live in a world in which humans have so profoundly altered the geological and material development of the planet that its entire survival is at stake. However, I also think there is a risk in the current proliferation of the term: first of all, the word “we” characterizes a lot of talk about the Anthropocene. Who exactly is this “we”? Certainly not everyone is affected in the same way. So it is important to come up with alternative stories that do not gloss over power imbalances. Then there is also what Donna Haraway has pointed out: the Anthropocene easily turns into a very Christian narrative of “Man” contemplating his own death. It’s capitalism that got us into this mess, after all.

EG: I think we’re still in the Holocene. Although there are many landscapes that are definitely in the Anthropocene, the Anthropocene is a proposed term. I want to say it’s a conceptual device that allows us to say that human disturbances have reached such a massive scale that we’re changing planetary conditions in very uneven ways; that there are what Rob Nixon calls “slow violences,” and we need a way to tag them.

We need a way to mobilize around these huge destructive machines of neoliberalism. I think it is useful to call that the Anthropocene. People like Donna Haraway, for example, want to think about the Capitalocene while Anna Tsing wants to say Plantationocene. There is also the Cthulhucene. In all those terms I think there’s an attempt to name how we got here.

There is an attempt to ask: What is a dominant figure that might tell us more about our contemporary condition? Is that plantations? Is that capitalism? Is it the figure of Anthropos, which is the Greek word for human? But it’s in a way making that figure visible, whatever it is, so that we can unmake it, so that we can undo certain agencies that it’s managed to unleash into the world.

In saying that it’s Anthropos, it’s saying that it’s the human being that has caused planetary disturbance and it’s basically knocked the Earth off its axis, so that sunlight has changed, photoperiods have changed, wind directions have changed. We’ve changed the temperature of the Earth. That is crazy. If it’s a figure of a human that allows us to say, “How do we undo that?,” then become more human, then I think it’s useful. I hope it’s not a fad because we’ve heard these warnings since the 1970s.

BS: Yes, I agree with Elaine: the potential of the term is that it creates the possibility to get out of former anthropocentric thinking and modes of being in the world. But we need to combine a discussion of the Anthropocene with a sensibility for the limits of human omnipotence and its colonial trajectories. And that’s why ferality and ruderal ecologies are important.

EG: We’ve heard the warnings since 1920, so we can probably say we’ve been hearing about this for a very long period of time. Obviously, we have not listened to the warnings carefully enough though, and so that is why we’re in the situation we’re in. I think the Anthropocene is a useful term in that sense. My worry about it is that if we use it too much, we might stop hearing what is useful about it; we might get desensitized, though I hope we don’t. I’d also add that the world has ended for many groups, depending on what point of view you have. The Earthrise image, for example—from the Apollo missions—gives us a sense of the blue Earth. We’re able to say we’re in the Anthropocene because of that image, but for some groups, a river was the world, a forest was the world. For certain species, a leaf might be the world, and so we’ve ended those worlds many times before.

CP: So you are saying that the question is: “Whose Anthropocene?”

EG: Yes, definitely, which is, I think, one really important seminar that’s here. There’s also a certain level of identity politics that it invokes, as I think Lesley Green said in her input statement: “How do you not go back to that, but then at the same time how do you have politics without that?”

BS: It is unsettling to see how easily earlier feminist and postcolonial critiques of identity politics and the nature‒culture divide seem to be forgotten in discussions about the Anthropocene. I think the key challenge is to reconnect these critical interventions with the concerns raised by the Anthropocene. The question is not simply a matter of which standpoint, of who is speaking, but of who or what do we connect with, who is to be represented, and what bodies come to matter as we engage with the Anthropocene.

This interview was conducted on behalf of Bad at Sports and the HKW.