Small Agency in the Nuclear Anthropocene

Local Words for the Palomares Accident

The science of global changes emerges from a period when large-scale international research defined by the military-industrial-academic complex was the norm. Historian of science Xavier Roqué subverts this historical supremacy of big science in the nuclear age by highlighting the role of small-scale science and local research. Through the case of the nuclear accident at Palomares, Spain, he shows the importance of local actants and scarce resources in registering and understanding Anthropocene-scale phenomena.

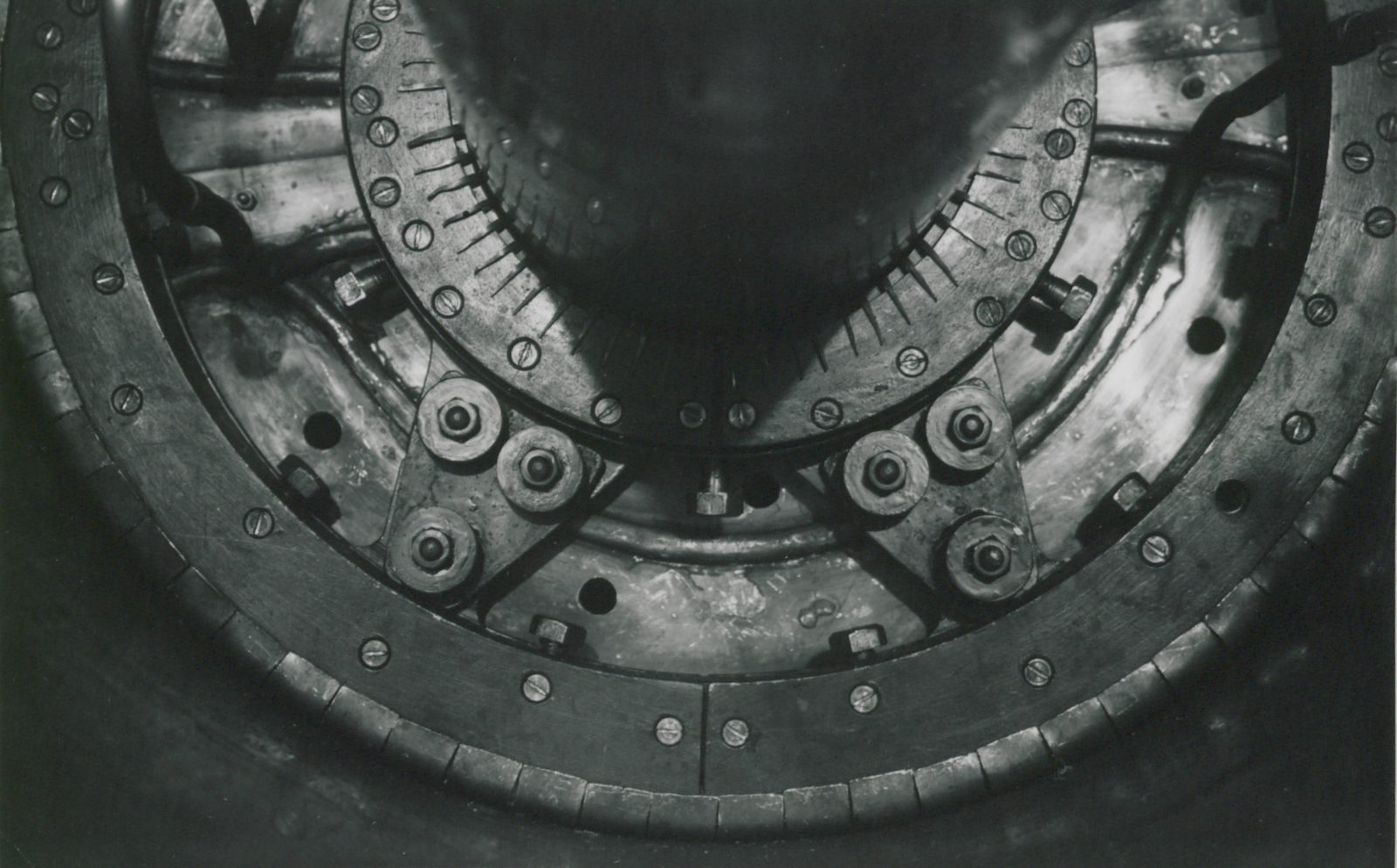

Journalist and environmental activist Jordi Bigues was twelve years old when, on January 17, 1966, a B-52 US Air Force bomber and a KC-135 tanker collided during an aerial refueling operation over Palomares, a small town on the southeast coast of Spain. The planes exploded and only four crew members survived. Along with the planes’ debris fell four thermonuclear bombs. One landed in the sea, and several kilograms of Plutonium were dispersed around Palomares when two of the devices hit the ground.

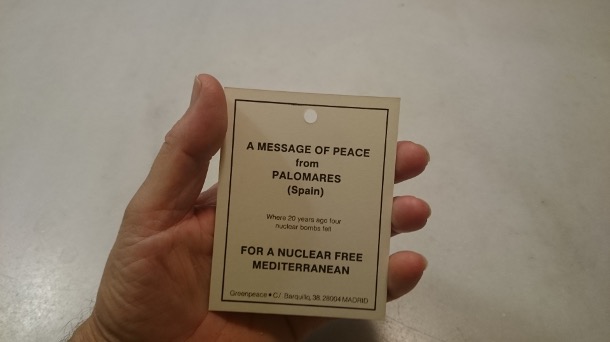

Twenty years later, as vice president of Greenpeace Spain and together with the young Socialist mayor of Palomares, Antonia Flores, Bigues led a vigorous, grassroots, scientifically-informed campaign to secure the people of Palomares’ right to file claims for compensation as victims of nuclear damage. The twenty-year legal deadline to do so loomed, and no clinical record had yet been handed to victims of the accident.

Fifty years later, Bigues did not want the memory of the campaign to fade away.

Bigues is a tall, earnest man. Late in 2015 he wrote to us at the Institute for the History of Science at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, seeking to deposit his personal archive documenting one of the most serious, well-known nuclear accidents in history. Over the next few months, we met several times at the university and at a local cafe near his flat in Barcelona until he was ready to hand over his papers for us to catalogue, digitize, and eventually publish online. We recently finished this process in the same unassuming way he had treasured the papers for decades in a plastic red Bauhaus box: by spending sparsely, working quietly, and strengthening personal ties.1 He was aware that the files had the potential to rewrite the story of the Palomares accident—a story which has been much told, but not so much researched.2

Bigues’ archive invites us to ask how small agency contributes to our knowledge of the nuclear Anthropocene: How did work by independent scientists and public health experts feature in the 1986 Palomares campaign? How can historical work on a small personal archive reframe long-standing accounts of a critical, consequential accident?

The Anthropocene event is commonly discussed in terms of large actants operating at a global scale. In the case of the nuclear Anthropocene, these range from national agencies to international committees, through nuclear power plants, mines, and waste management sites. This approach is consistent with the historiographical prominence of large-scale research at the expense of other ways of knowing, particularly small-scale research. Ever since Big Science became a dominant style of organization in the long 1960s, little science has been taken for granted.3 As Big Science was subject to scholarly analysis and criticism, no effort was made to investigate its little ancestor.4

By the turn of the century, however, a renewed interest in small science was noticeable, perhaps indicating it had never quite faded away. In 2001 Steven Shapin pointed out that one of the things some scientists were “violently critical of [is] the hegemony of Big Science at the expense of Little.” And Simon Werrett has recently concluded that the early modern approach to “achieving a balance between spending and buying new and saving and making use of things” seems to be “reemerging today:” “While people in the late-twentieth century supposed that the future of science would be mostly ‘big,’ as we enter the twenty-first century, it seems that the future will also be small.”5

Small science refers here to work by teams of up to ten researchers, producing first-rate, disruptive knowledge with frugal means. Referring to the British Antarctic Survey scientists who in 1985 first provided evidence of stratospheric ozone depletion, for instance, Sebastian Grevsmühl has asked how could “a little-known team with a relatively modest budget” beat NASA at the discovery of a hole in the ozone layer.6

The Superconductivity Group at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona provides another example. This six-person team, working in a makeshift lab, creates proof-of-principle devices displaying new, technologically promising phenomena, such as magnetic hoses, cloaks, and wormholes. Their work has featured in leading journals and drawn substantial media attention, yet the group keeps working in small premises with relatively simple means.7

The makeshift laboratory of the Superconductivity Group at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and a proof-of-principle magnetic hose. Photograph by Xavier Roqué The makeshift laboratory of the Superconductivity Group at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and a proof-of-principle magnetic hose. Photograph by Xavier Roqué

One last example will also serve as a metaphor for my point: The Dragonfly Telephoto Array, a small-scale observational astronomy project. A series of commercial 400 mm telephoto lenses are connected to one another in an array that looks like a dragonfly eye. The system reveals ultrafaint galaxy features and “a wealth of structures that are not seen at higher surface levels,” that is, when using large telescopes.8 Dragonfly and small science projects generally are not about doing the same with less, or having to make do with the limited resources at your disposal. Rather, they are about finding the right tools and doing things you could not do without such tools, and specifically could not do in a “big” way. These effective ways of doing do not seem to belong in the world of contemporary science, yet they contribute significantly to knowledge and unveil phenomena that would otherwise remain invisible.

As we turn to the historiography of the nuclear sciences, the argument appears to reverse in time. Once, we had to strive to reveal the manifold industry and government relations of nuclear scientists up to WWII, and to challenge heroic tales of individual ingenuity.9 Our critique was of a piece with an increased awareness of the value of artisanal knowledge and manual skills for the emergence of modern experimental science.10 By the end of the nineteenth century these cultures of precision had been incorporated in academic and industrial settings through the creation of research laboratories in universities and companies.11

Now, by contrast, we must strive to show the continued relevance of small-scale research practices after WWII, and to challenge the tale of the march of large scientific organizations. Research on the history of the nuclear age has not just involved policy makers, scientists, state officials, and businessmen… but also workers, activists, and independent experts. As Gabrielle Hecht asks, “how did Marcel Lekonaguia, who mined uranium in eastern Gabon for over three decades, experience nuclear things before he and hundreds of other Gabonese workers learned that radioactive elements had penetrated their bodies, their houses, their water, and their land?”12 Valentines-Álvarez and Macaya have discussed fun and playfulness as forms of resistance to “national energy plans, expert discourses, and vested interests.”13 Similarly, I ask about the experience and actions of seemingly lesser actors. How are small actors relevant for making sense of the nuclear Anthropocene? How do they contribute to our understanding of it? Can the category of small science, however problematic, help us broaden our representations of the nuclear Anthropocene and our understanding of how it affects whom?

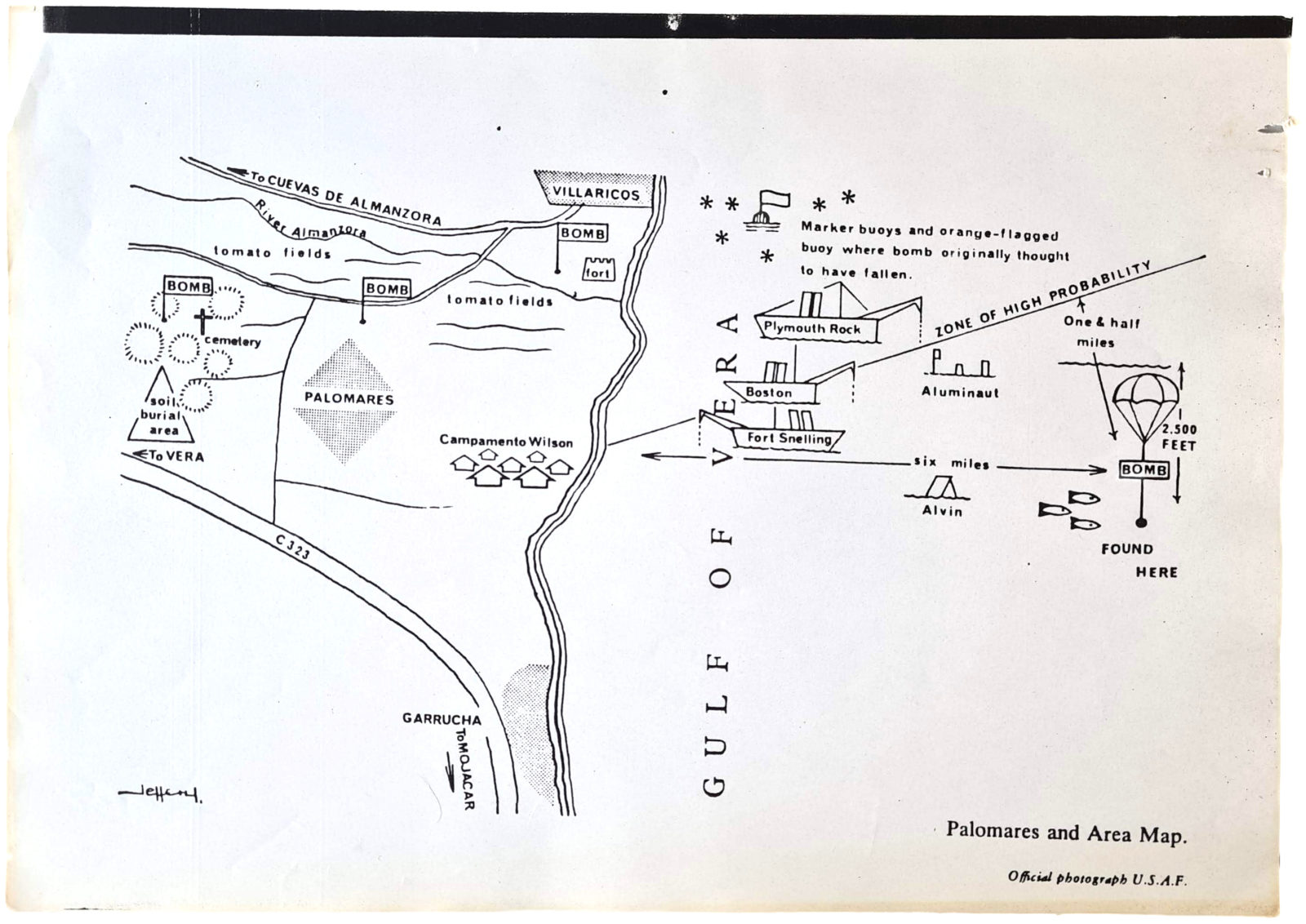

Map of the Palomares accident included in “Palomares Zone Zero,” a draft proposal for Dina Hecht’s film Broken Arrow 29 (1986). From the Bigues Palomares Papers, DDD-UAB, PALO_0167

Immediately after the accident over Palomares, the US and Franco’s governments mobilized the army, the diplomatic corps, the national nuclear agencies, and the press. The US military undertook the removal of contaminated soil. Three months after the accident some 1,000 tons of radioactive soil were shipped to the United States and buried in a nuclear cemetery.14 Decontamination certificates were swiftly issued to owners of land, and the Spanish Nuclear Energy Board (Junta de Energía Nuclear) undertook a long-term program to analyze radiation levels in the population. Overall, events in the few first months after the accident have focused much of the scholarly and public attention on an accident which has, from the outset, been intensely represented in the media.15

African American servicemen haul plutonium-contaminated tomato plants in Palomares (1966). Image from John Howard, The American Nuclear Cover-Up in Spain. London: The British Library, 2017. Photograph in the public domain

The rapid initial reaction to the accident contrasts with the protracted management of its health and environmental issues. Victims of the accident are often missing from public discourse and media representations. Florensa argues that they have been actively invisibilized, along with the radiological risk.16 The release of the Bigues’ papers, which include formerly unavailable evidence on the victims, has not changed this situation. Even though the new evidence has not gone unnoticed, film-makers and script writers have found it hard to let the voice of the victims be heard. Oddly, the papers include the script of Broken Arrow 29, a 1986 film by Dina Hecht advocating the creation of the Palomares Research Group with the aim “to interact with the local inhabitants and [film] the interaction as and when it takes place”. Hecht also meant “to merge research and filming into a unified activity —that is, to superimpose one on the other.”17

Bigues and Flores have also sought for decades to render the effects of the accident visible. In 1985 they commissioned an independent expert report, gathered information from official archives that has since been lost, and promoted the continued informed discussion of the situation, raising questions about risk management and public health that directly challenged the policies of the Spanish Nuclear Security Council (Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear, CSN) and the Nuclear Energy Board (Junta de Energía Nuclear, JEN). The scope, impact, and nature of the campaign, as well as the relevance of Bigues’ careful custody of the memory of these events, can be illustrated in two moments of this contested history.

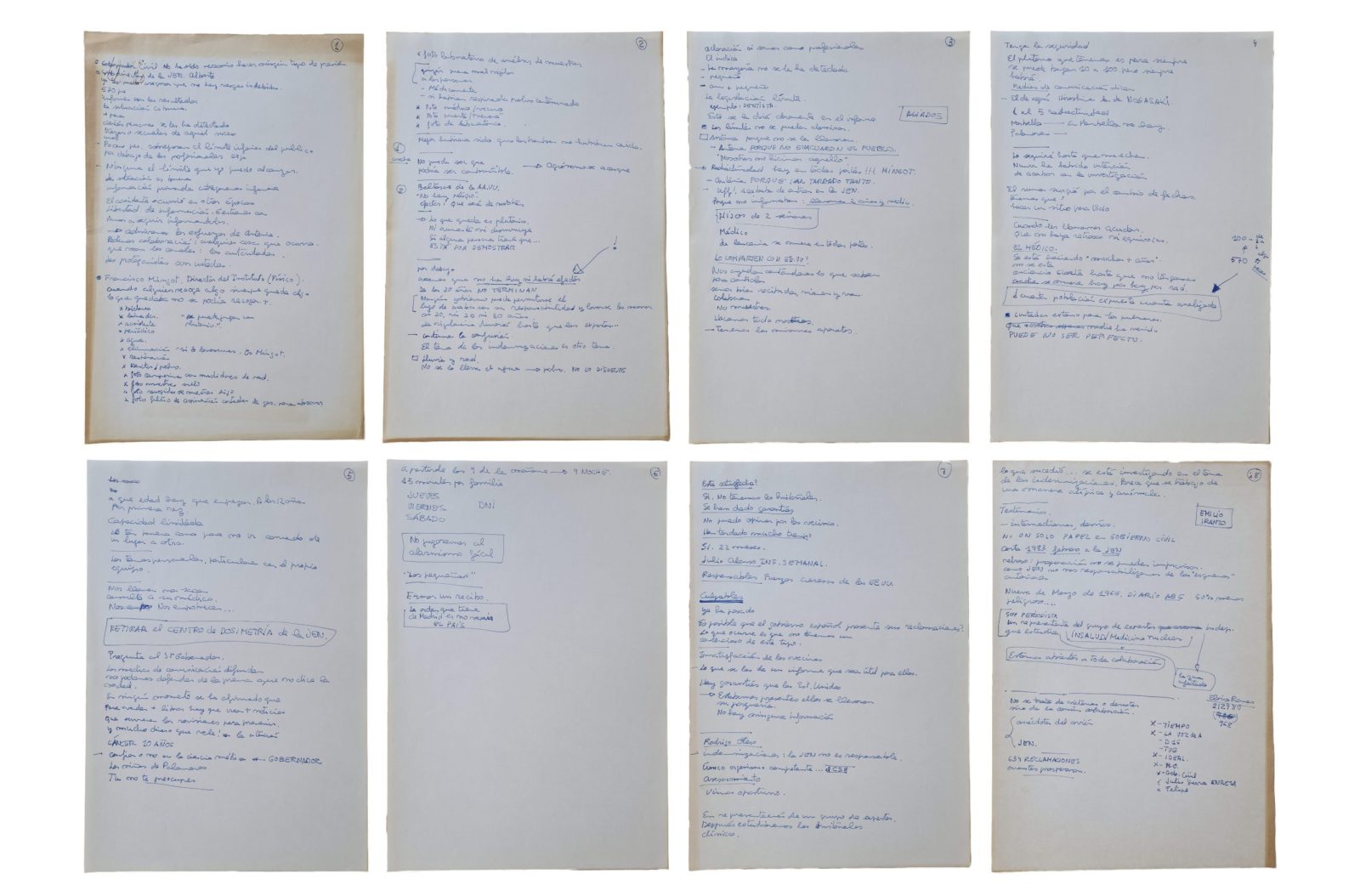

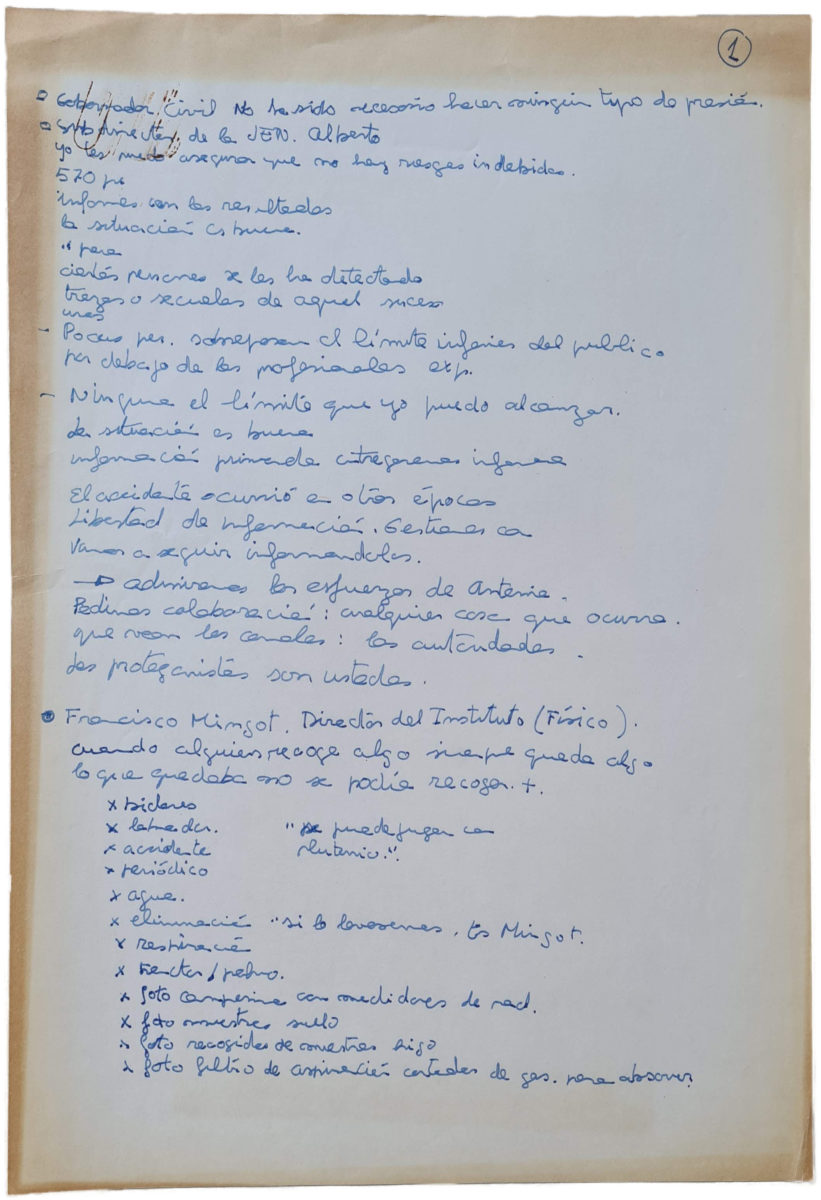

The first took place on November 6, 1985. Officials from the JEN and the CSN, including A. Rodrigo Otero, vice director of the JEN, and F. Mingot, director of the Institute for Radiological Protection of the JEN, appeared before the people of Palomares. Yielding to repeated demands, and probably intending to settle the issue, the CSN had agreed to the partial release of the individual clinical reports done by the JEN. Until now we just knew about this appearance (comparecencia) through press reports and the accounts given by some of those present, like José Herrera. Bigues, however, took and kept meticulous notes of the event, allowing for a direct, more faithful account of the rhetoric employed and the public reaction it generated.18

The JEN officials delivered soothing words, reassuring the neighbors that there was “no undue risk” and that “no one dies these days because of radioactivity, [because it] is everywhere!”19 They made candid admissions of impotence (“there is no way to secure the limits”), along with implicit references to the transition from dictatorship to democracy (“the accident took place in other times”), and explicit references to international cooperation (“[the US] helps us telling us what they know,” even if “they come and go”). There were also vain attempts to give agency to the people (“you are the protagonists”) by showing images of farmworkers with radiation counters. The appearance fell much short of its aim and did not deactivate, but rather strengthened, ongoing efforts to secure independent expert advice.

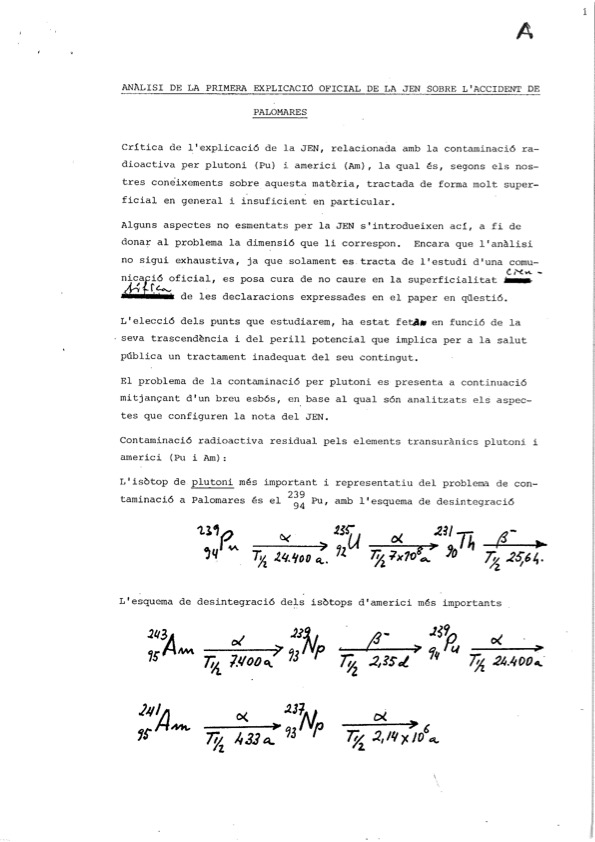

The second event was the publication, in September 1986, of a counter-analysis of the official report submitted to the Spanish Parliament by the Nuclear Security Council. Worried about the health effects of residual radioactivity, Flores commissioned an independent report by the Center of Analysis and Sanitary Programmes (Centre d’Anàlisis i Programes Sanitaris, CAPS), a group of scientists and health workers based in Barcelona. The report was written by four physicians with expertise in social and public health: Catalina Eibenschutz, Salvador Moncada i Lluís, Josep Martí i Valls, and Eduard Rodríguez i Farré, who had published on radioactive pollution and the biological effects of radiation. Beyond just working to complete the mayor’s request, the experts sought to publicize knowledge about the accident, make visible the dangers of nuclear arms, and above all “to check, clarify and question the information, the analysis, and the conclusions included in report by the Nuclear Security Council.”20

The CAPS report speaks to both the range and constraints of non-official investigations and communicative actions. The 110-page booklet included a 63-page report, as well as a facsimile reproduction of the CSN report.21 It was endorsed by a host of local and international associations, and Peter Taylor, director of the Political Ecology Research Group at Oxford, wrote the preface. Still, the work was done locally, and what little financial support CAPS had was devoted to the publication of the booklet and no funds could be allocated for research or writing.

The authors had to content themselves with data gathered by the JEN, the only body allowed to make measurements in the area. Conceived as a tool of civic and scientific pressure, the CAPS report showed the methodological flaws and lacunae in the CSN report. It was submitted to Palomares city council, but also to the Health Council of the Junta de Andalucía (Andalucía’s regional government), the Nuclear Energy Board (JEN), the Nuclear Security Council (CSN), the Industry Commission of the Spanish Parliament, the Health Ministry, and the Spanish Ombudsman (Defensor del Pueblo).

The CAPS report was fairly critical of the way state institutions and scientists had handled the people of Palomares, noting “how the technical-professional state apparatus decides unilaterally the degree of risk acceptable for a population, without even talking to them.” No criteria for acceptable risk had been defined. It quoted a US Air Force report describing Palomares as an environmental laboratory, “perhaps the only one allowing for the observation of a cultivated area.” It also compared the levels of residual contamination with those of other nuclear sites and made detailed recommendations on radiation monitoring and its effects on people.22

The CAPS report was a small science effort. A four-person team with scant means was able to produce and circulate expert advice that countered official accounts. The contribution of those who campaigned three decades ago has been neither small nor ineffective. Above all, it pre-empted the application of the Law of Nuclear Security and extended the victims’ right to file claims. Beyond the immediate effects of their work, the CAPS report has remained an important piece of evidence in the ongoing debate over the management of residual contamination in Palomares, counterbalancing other accounts that ignore people in questions of both contamination and management.23 The report has also served to pool together—to raise public awareness, which it has done to great effect—scientific research, journalism, visual media, and exhibits.24

Labels created for the 1986 campaign to raise awareness about the victims of the Palomares accident’s rights and claims. Courtesy Jordi Bigues

Isabelle Stengers’ slow science, Manu Prakash’s frugal science, Simon Werrett’s thrifty science, Sebastián Ureta’s ruination science… Since the turn of the century, an emerging concern for small ways of knowing and doing is clearly discernible.25 My work on small science aims at placing such concerns in historical perspective. While potentially as misleading as science/technology or idea/thing, the dichotomy Big/small may still serve some purpose.26

But this may not be such a strong dichotomy. Work on peripheral accelerators has shown that old, central equipment can find new, unexpected uses upon relocation. Cyclotron, a documentary film by Jahnavi Phalkey, “tells the story of the kind of science that is often ignored by chroniclers, done in a relatively small institution, unpeopled by the big names.”27 The nuclear scientists trained at Chandigarh may pursue their careers in bigger high-energy labs, suggesting a role for small-scale practices within larger scientific collaborations. Both Olof Hallonsten (Small science on Big Machines) and Catherine Westfall (“Thinking Small in Big Science”) have reflected about the size and character of the work done in high-energy labs.28 This approach may also prove useful when applied to the Anthropocene Working Group, which produces global knowledge through the contribution of many smaller, local teams.

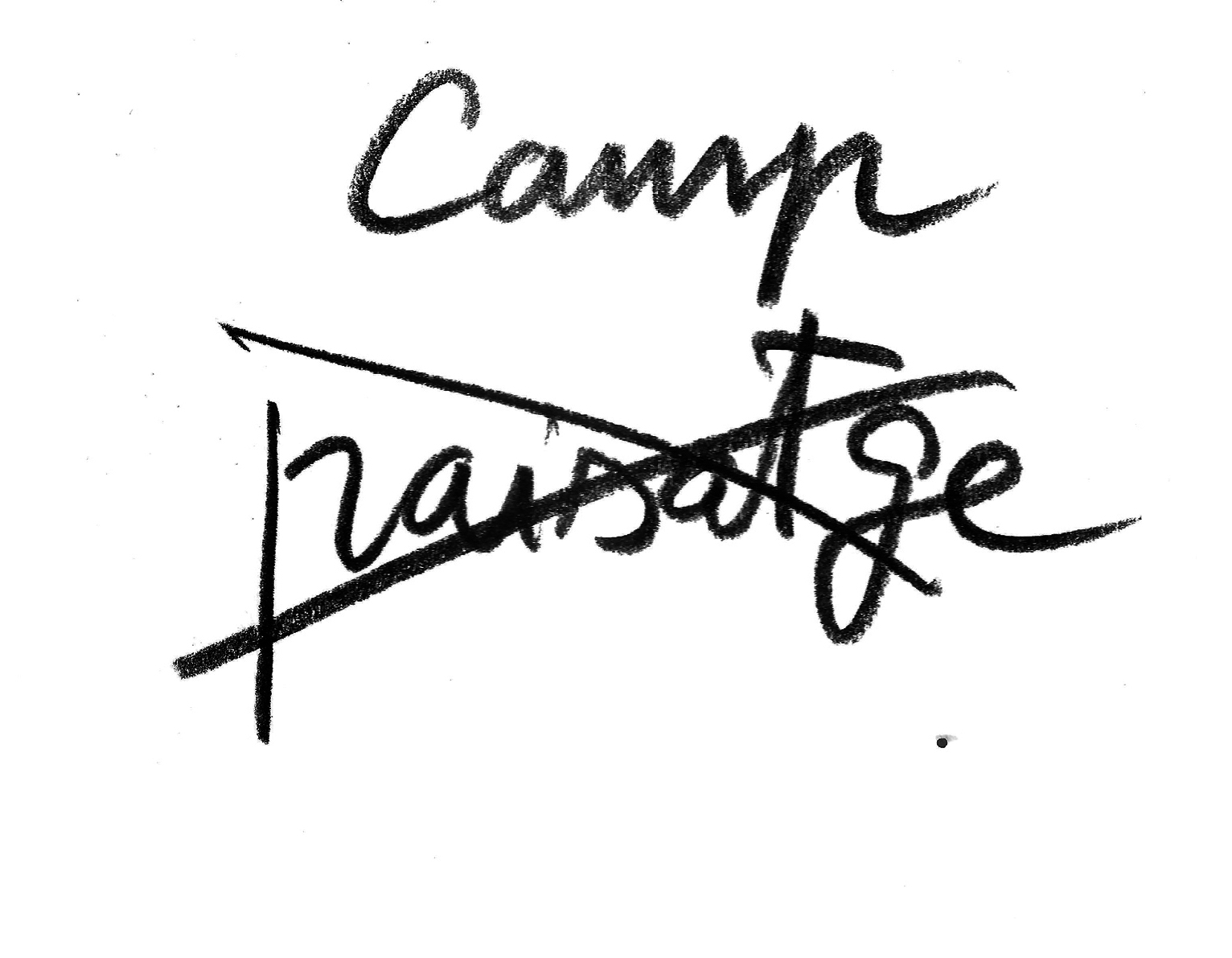

In Local words (Paraules locals), the artist and writer Perejaume discusses place. He decries “landscape” (paisatge) as a detached place to be admired from the outside or from above, to be molded at the viewer’s pleasure. Instead of landscape, he talks about “field” (camp): a place you belong to and are part of, both affecting it and being affected by it. Although Perejaume does not write with field physics in mind, his image is very physical, breaking down spatial and political hierarchies: “It is no good to draw any judgement from places, nor any hierarchy of the ones over the others. Places, with regard to their most essential aspect, which is to weight in the world, do not rival, they all have their weight. No place is repeatable and, therefore, any corner of the world is as worthy of reverence as the most.” Big Science as a landscape, small science as a field. Perhaps we will have to resort to small actants, local words, and unrepeatable places to make sense of and take action in the global nuclear Anthropocene.29

“Camp” [field], “paisatge” [landscape]. Drawing by Perejaume, © all rights reserved Perejaume

Xavier Roqué is Reader in History of Science at the Institute for the History of Science of the Autonomous University of Barcelona. His current research deals with the history of small-scale research practices.

The author acknowledges the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, project PID2019-105131GB-I00.

Please cite as: Roqué, X (2022) Small Agency in the Nuclear Anthropocene. Local Words for the Palomares Accident. In: Rosol C and Rispoli G (eds) Anthropogenic Markers: Stratigraphy and Context, Anthropocene Curriculum. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. DOI: 10.58049/zas4-g046