Real Estate River

The Mississippi as Amenity

Morgan Adamson chronicles the historical mechanisms that have seen the Mississippi shift from an industrial river to what she terms a “real estate river.” Far from offering a blank slate, she argues, without the intervention of radical imaginings regarding the river’s future—which acknowledge past violence and injustices—deindustrialization will merely serve to further the long history of extractive processes associated with the Mississippi’s riverfronts.

Redevelopment of St. Paul Image by AECOM Properties.

In the summer of 1997, Mayor Norm Coleman’s office published a document entitled “Saint Paul on the Mississippi: Development Framework.” The detailed report describes a “profound transformation” underway in the city of St. Paul, as Coleman puts it: “not only a physical transformation, but a transformation of the very spirit of the Capital City.”1 At the heart of this transformation was, in the words of the report, the “retreat of the industrial glacier,” which had revealed a “vast terrain of opportunity in the river valley.” In the era of climate change, the phrase “retreat of the industrial glacier,” coined by urban designer Ken Greenberg, unwittingly evokes images of glacial retreat, but more on that later. What concerned city planners and developers in the 1990s was that industry’s “retreat” would mean substantial landholdings along the river’s edge being vacated, leaving new spaces from which the city could conjure its postindustrial future.2 The “development framework” detailed by the report includes a combination of environmental and infrastructural improvements aimed at giving the city of St. Paul a “competitive advantage in an increasingly globalized world.” The “new spirit” of the city projected by Mayor Coleman, then, was one that fully integrated the Mississippi into the urban fabric of St. Paul, understanding it as a crucial amenity for urban life and a propeller of economic development in a postindustrial era. St. Paul—like cities across the US wrestling with deindustrialization—had been developing plans for “urban revitalization” along its waterfront since the 1980s, commissioning the Riverfront Development Corporation in 1984 to connect public assets with private interests to oversee investment along the Mississippi.

In what might be seen as the culmination of the city’s efforts over the past 40 years, the Riversedge development, approved by the Ramsey County Board in July of 2019, completes St. Paul’s postindustrial makeover. Composed of four towering glass structures, like those on the waterfronts of cities from Singapore to Miami, the 788-million US dollars Riversedge project includes a luxury hotel, condos, and apartments, one million square feet of Class A office space, and a public walkway that connects them to the river. Riversedge will be constructed atop land owned by the city, formerly home to West Publishing Company headquarters and printing facilities, refrigerated storage, and a county jail. The project was proposed by AECOM, a multinational engineering and architectural firm that has worked on a number of high-profile projects, including the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, the World Trade Center, Dubai Health Care City, and numerous international airports. AECOM is asking for $80 million from the city to subsidize the project, which Ramsey County hopes to partially cover through a $40 million State bonding bill. This is on top of the $11 million the city has already invested in anticipation of a large-scale development of the site, having demolished the existing remnants of industrial infrastructure in 2015 in order to attract developers.

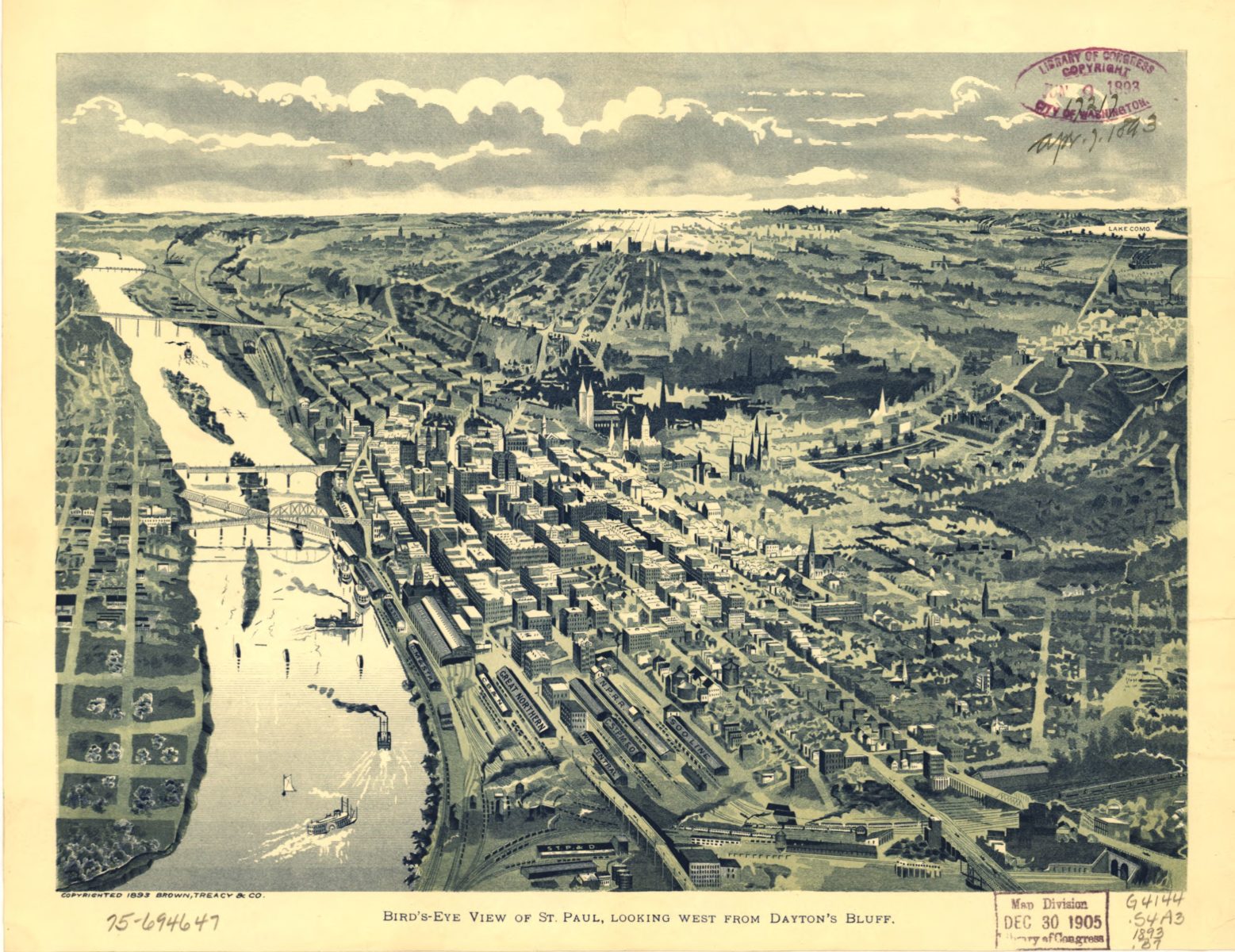

Bird's-eye view of St. Paul, 1893 Image courtesy of the Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress

The transformation of St. Paul’s orientation to the river in the past decades exemplifies what we might understand as the shift from the industrial river to what I am calling the real estate river. In Capital City, Samuel Stein argues that the deindustrialization of US cities has given rise to the “real estate state” in which “real estate capital has inordinate influence over the shape of our cities, the parameters of our politics, and the lives we lead.”3 With the decline of industrial capitalism, real estate development has become a primary economic driver in cities, dictating the terms through which space is organized and land use is determined. In the Twin Cities, the Mississippi’s diminishing importance as an industrial river has given rise to a situation in which the river now serves as an amenity that augments the value of real estate capital. In this context, decisions made about the river’s future as it flows through the Twin Cities are intimately wrapped up in considerations of the immense value of the land adjacent to it. Even positive social and ecological interventions that reimagine the postindustrial river often unwittingly dovetail with the interests of real estate capital and developers.4 In other words, deindustrialization is a process that is not necessarily about “liberating” the river but subjecting it to the new necessities of capital accumulation.

Take, for example, the Upper Harbor Terminal (UHT) in Minneapolis: the longest contiguous stretch of real estate on the upper Mississippi, which served as the river’s northernmost port until it closed in 2014. Located in the historically African American neighborhood of North Minneapolis, the UHT was built atop of the demolished homes of residents in the 1960s and has since barred the neighborhood access to the riverfront. Like the proposed site of the Riversedge development in St. Paul, the UHT sits on land owned by the city, and, like the St. Paul redevelopment, this land is being offered to the private sector to build for-profit developments, heavily subsidized by taxpayers. The proposed redevelopment of the UHT looks strikingly similar to the kinds of redevelopment projects that have been taking place in deindustrialized spaces across the US since the 1980s. Geographer David Harvey describes this process in the city of Baltimore, where throughout the 1960s deindustrialization and racial turmoil led to white flight and a declining tax base.5 The city’s solution to this crisis was to finance massive waterfront developments, such as the Inner Harbor Project, in order to attract capital back to the city center. Through bonding bills that served as giveaways to the finance and real estate industries, the developments created low-wage service jobs in place of the industry jobs that had been lost, whilst fueling the gentrification of historically African American neighborhoods.

This kind of neoliberal city management fueled the rise of the real estate state in the 1980s and 1990s, where public resources were given over to private developers to fulfill the promise of economic revitalization. The current redevelopment of the Minneapolis and St. Paul riverfronts follow strikingly similar patterns. The original proposal for the UHT redevelopment by United Properties and Thor Companies—which included a “destination” music amphitheater, a hotel, retail space, housing (the majority of which is market rate), and parkland—was sold to the neighborhood and the city through the language of economic revitalization while simultaneously offering only low-wage, service-sector jobs to the already marginalized neighborhood in which it was planned. Against the backdrop of intense community pressure, before it was approved by the city council the developers offered some concessions, removing the hotel from the concept plan and adding a commitment to “community ownership models” for some of the retail space. With the formation of a Community Planning and Engagement Committee, the developers and the city offered only a muted hope that the core issues of racial and environmental justice would be addressed as the redevelopment is pushed through. Already, property values around the site are spiking, accelerating the ongoing processes of speculation and displacement taking place in North Minneapolis.

The story of the UHT reflects the ways that the river remains a site of extraction, where publicly held land is mined by the forces of financial speculation, and where city governments facilitate the flow of capital to and from these extractive spaces. Beneath the talk of “economic revitalization” and the boosterism of city officials lies a deep impotence of advocacy for a just social ecology and a feeble interest in mitigating the transfer of public wealth into private hands. These dynamics come into stark relief when we examine the Riversedge development in St. Paul. In a metropolitan area currently in the midst of one of the worst affordable housing crises in its history—like many cities across the country in the grips of the real estate state—the proposed Riversedge development in St. Paul contains no affordable housing units. Instead, AECOM has proposed to “give” the city a paltry $5 million to be spent on affordable housing elsewhere (a mere fraction of the $80 million it is demanding from the city to build the project). Like with the UHT, small concessions are offered to appease the public while largely excluding it from the enormous wealth to be generated from this publicly owned land. While cities are desperate to increase their tax revenue through projects like Riversedge, as Harvey and many others point out, there is little evidence that public subsidies of real estate developments actually benefit everyday citizens. In its stark reproduction of economic and spatial inequality, Riversedge exemplifies the vision of the river as a site of consumption and luxury, where public access to and interaction with the river functions as an amenity that increases land values and land speculation.

As it flows through the Twin Cities, the transformation of the Mississippi into a real estate river typifies the grip that real estate capital—and the neoliberal civic-management strategies that facilitate it—have on our collective imagination of the river’s future. While civic leaders looked at the “retreat of the industrial glacier” with a sense of possibility at the close of the twentieth century, in the present we should approach any such enthusiasm with suspicion. As the industrial glacier retreats in places like Minneapolis and St. Paul, it leaves in its wake not a tabula rasa ready for new development, but deep layers of sedimented violence. Indeed, as we face the reality of actual glacial retreat and the possibility of the end of life on the planet as we know it, the deep wounds of colonial conquest and the industrial era confront us like never before. In the case of the Twin Cities and the Mississippi, the story of industrialization is inseparable from the expropriation of land from the Dakota people, their displacement and attempted genocide throughout the nineteenth century, and the ongoing legacies of settler colonialism today. Likewise, as the story of the UHT lays bare, the histories of racial violence and the displacement of African Americans, which have been constitutive of the industrial Mississippi since the time of slavery, still haunt it today. To say the Mississippi is an Anthropocene River, to emphasize human impact and to imagine its different futures, is also to contend with the colonial and racial violence that took place alongside the massive infrastructural interventions into the river’s flow and its attendant ecological degradation. In significant ways, the retreat of the industrial glacier is not the harbinger of Mayor Coleman’s imagined “new spirit”; it marks not a break from extractive processes but a continuation of them. The real estate river projects onto the river and its shores employs a similar settler imagination to the one that shaped it at the beginning of the industrial era. By failing to truly confront the myriad violences of that era, it threatens to repeat them.

How do we understand the river’s value beyond that of an amenity for real estate capital or an entity that provides ecological or other “services” to the public at large? How might the values of reconciliation and reparation drive our approach to the river’s future? Whose voices should be foregrounded, including non-human actors? As we witness the intensive land grab currently taking place on the Mississippi’s shores, let us form a radical imagination that looks beyond, and struggles against, the terms set by the real estate state.