Perspectives and Politics

A Co-evolutionary Reflection

The search for the origin of the Anthropocene and the technosphere is not only a descriptive endeavor: whether we agree on the Neolithic, the Industrial, or the Atomic Revolution as origin points, each has very different consequences on what we perceive as the core problems of the Anthropocene and how to go about solving them. In her reflection, Simone Schleper, recaps in how far the seminar did or did not tackle the question of what a co-evolutionary perspective on the emergence of the technosphere might mean for environmental governance and politics.

Many words of caution were articulated: it was too early to discuss technospherical politics; the concept was still too young and fragile—so it was felt. And, in fact, we were not sure whether we were talking about one technosphere, perhaps the one marked by the complex interaction on multiple scales of socio-technical systems defined in the work of Peter Haff in 2014.1 Maybe we were instead talking about multiple technospheres pertaining to fragmented publics in different parts of the world. What might help us on the way, then, is to ask why the concept of the technosphere emerges now, and why we seek to understand it—what we want, can, and should do with it—questions at least as weighty as its earliest geological manifestation. Someone interested in environmental history might see the concept of the technosphere as part of a long tradition of thinking about global societies and environments. In fact, the technosphere has had previous moments of popularity. One conceptualization from the late 1960s I would like to share here, despite its contingent historical socio-technical derivation. The ideas underlying that technosphere emerged from a similar perception of urgency regarding the state of the global environment. Therefore, it might serve as an example, perhaps telling us something about possible mistakes and opportunities linked to the making of big concepts.

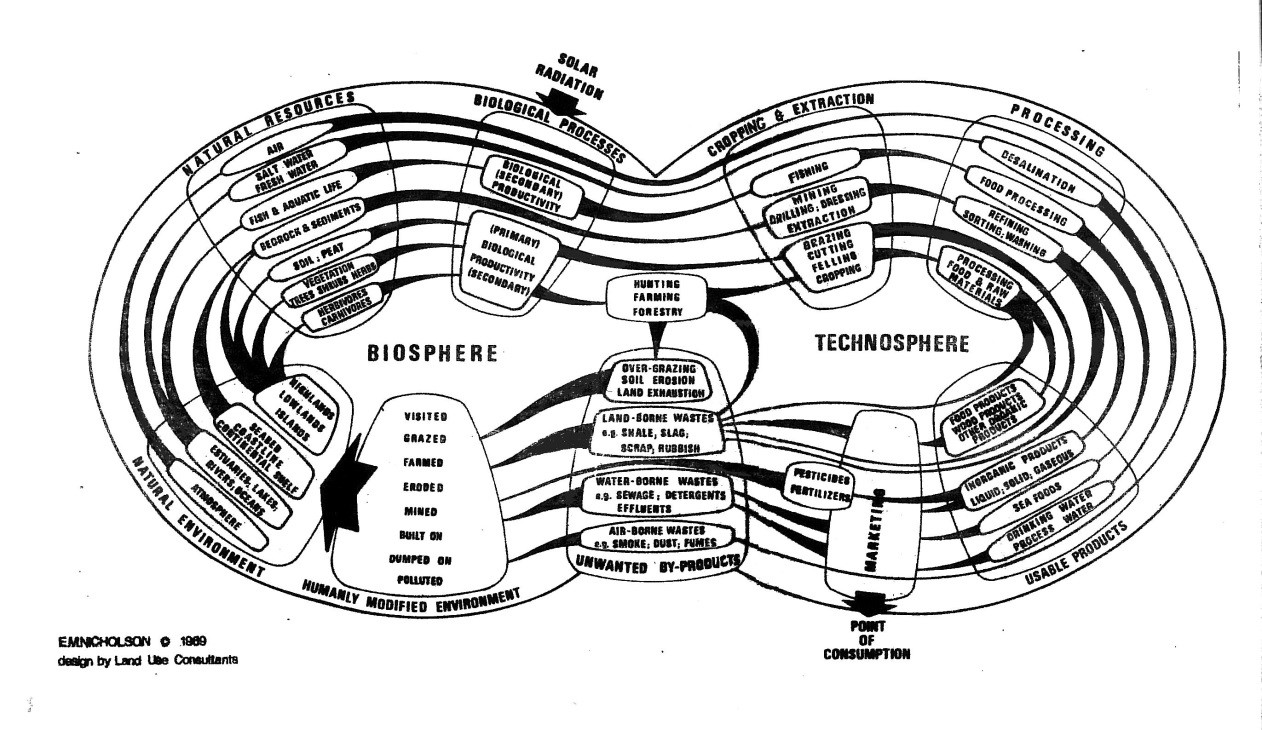

“Diagram of the Biosphere and the Technosphere” | Land Use Consultants, LUC, for Edward Max Nicholson, 1969 Courtesy of the Linnean Society Archives, London

The diagram presented here was commissioned in 1969 by Edward Max Nicholson, the head of the British Nature Conservancy and the Convener of the Conservation of Terrestrial Communities Section of the ten-year big science program on ecosystem ecology, the International Biological Program (IBP).2 In this function, Nicholson had taken part in several meetings with high-level scientists at the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) earlier that year. Here, at one point, the idea of the interdependence between the natural and the socio-technical environment, the biosphere and the technosphere, had been discussed.3 Nicholson commissioned the British land-planning firm Land Use Consultants to design an illustration for a Royal Society Symposium in 1969. Designed to function as an objective tool of demonstration, it showed society and nature as part of an interdependent system. According to Nicholson, ecological planning and rigid management were needed in order to avoid undesirable or even disastrous side effects of humans’ use of nature, such as overexploitation or industrial poisoning. With the “Diagram of the Biosphere and the Technosphere,” Nicholson illustrated the societal relevance of the work of his IBP section to audiences beyond the biological community. And he did so with some success. Nicholson used the diagram to address development experts at the Columbia University Conference on International Economic Development in 1970.4 In the following years, the same ideas inspired the environmental work in international organizations such as the FAO or the international Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE).5 The concept, moreover, became part of the intellectual background report Only One Earth to the famous United Nations Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm in 1972.6 With its ontology on the mutual dependency of nature and society, the diagram describes a particular scientific development related to both the natural sciences and technical engineering, namely the merging of cybernetics and early ecosystem ecology. In the 1960s and 1970s—which are the decades of environmental revolution and also the heyday of systems thinking—a philosophy emerged which was critical of the exploitive character of earlier periods, yet equally positivist about human capacity to know and to control. In particular, predictions of human population growth, depletion of the natural resources of the biosphere, as well as early ideas on the technosphere and concerns about the inappropriate use of technology and pollution resulted in debates about the limits to growth and calls for adaptation of social and environmental engineering to the working of natural systems.7

Nicholson, for example, was particularly intrigued by computational models of energy cycles, biological systems, and energy flows. In the 1950s, the introduction of computers allowed the simulation of functions of various systems. Likewise, systems ecology experienced a new growth. With the development of cybernetic approaches in ecology, and an improved ability to examine interrelated systems of life forms and their environment, Nicholson’s demands for universal principles of conservation and resource management found a scientific basis. Nicholson’s diagram suggested the existence of one coherent Earth system, encompassing the natural and the socio-technical world, with the same set of rules for the management and development of both. Our techno-scientific means of capturing, reproducing, and studying natural processes have developed considerably over the following decades, and our global problems in the age of climate change and economic crises are perhaps even more dramatic. Yet, similar notions on globality, interrelatedness, and interdependency of natural and social systems still underlie our understanding of the technosphere. Even the co-evolutionary perspective is a type of systems otology that aims at expanding traditional explanations of systems evolution that have discerned developments internal and external to individual systems, across different scales and sectors (e.g. genomic, social, cultural, or technological systems).8 This way, strict boundaries between what counts as one network and what counts as its environment are dissolved. Looking back at Nicholson’s diagram, we find his political ideas on environmental problem-solving quite different from those underlying the seminars of the Technosphere Campus. In retrospect, we can see that his ideology was representative of postwar, postcolonial technocratic thinking. Nicholson used this system approach—linking society, land use, and natural resource management—to back up his technocratic approach to land management and social planning. He was eager to secure planetary survival, but his claims were universal and undifferentiated and his ideas left little room for alternative voices and local participation. His peers in conservation criticized him as a consequence. Within UN agencies such as UNESCO and the FAO too, his technocratic approach was perceived as irreconcilable with international environmental and development politics.9 In the following decades, postmodernist theorists criticized such attempts to find unifying theories as products of predominantly Western, scientific imperialism.

This history should not prevent us from trying to further conceptualize or envision a co-evolved technospheric society. In order to operationalize the concepts of the Anthropocene and the technosphere beyond the academic community, they will have to become something more tangible. Yet this example might show that thinking and talking about the two concepts will have to go hand in hand with the willingness to think about their politics. All conceptualizations and diagrams have an inbuilt ideological dimension, simply by allowing for some interpretations and by excluding others. While concepts in turn shape the way we think about problems and solutions, they can be operationalized in different ways. And, in fact, by exploring the conditions for human agency in the technosphere, the co-evolutionary perspective may be in a good state to help us understand what may be possible and what may be impossible to change. In seeking to improve understanding of the interrelation between multiple systems and different scales—their diverse regulatory mechanisms, and the critical mass needed for social and technical change—co-evolutionary thinking may provide the theoretical bedrock against which to do so. On this firm ground, we can try to formulate new guiding principles of conduct for responsible innovation and environmental problem-solving: what we need is a perspective that allows for a translation between diverse ways of knowing and value systems on different scales. This sort of perspective would encourage civil engagement as well as additional interdisciplinary cooperation not only in marginal, experimental spaces like the Technosphere Campus, but also in bodies like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in which social and natural systems and sciences are still kept separate right up to the present day.