Outrunning the Anthropocene?

Countering coastal land loss by the rapid restoration of salt marshes

The main driver behind the movement of soil is human activity. In southern Louisiana, the engineered orchestration of the flow of sediments through water manifests in coastal land loss. In this piece, Ian Gray looks at the State’s comprehensive coastal restoration plan to discuss how attempts to restore the Louisiana coast often turn a blind eye to the impacts of the petrol industry—and its detrimental effects on coastal land and their communities, such as Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe.

Shrimp boats and elevated homes along Bayou Pointe-au-Chien; the community is made up mostly of members of the state recognized Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe. Photo by Ian Gray.

Donald Dardar lives on Bayou Pointe-au-Chien, a skinny arm of the vast marsh systems that make up southern Louisiana. Dardar, or Mr. Donald—as is the customary appellation around here—is a member and Second Chairperson of the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, a branch of the Chitimacha people. His family traces its presence in Pointe-au-Chien to at least the late eighteen century, when his immediate ancestors planted permanent roots on the edge of what is now Terrebonne and Lafourche Parishes.1 Deemed undesirable by encroaching white settlers, the bayou afforded his forebearers protection from the dispossessions and forced relocations that befell many other tribes in the same period.

Now, however, that protection is turning against the Tribe. This liminal zone, where the shrimp thrive and the oysters and crabs congregate, is coming undone. The very terre bonne, or “good earth,” under Mr. Donald’s feet is changing. It is vanishing, with increasing speed, beneath the waves.

Donald Dardar, getting ready to fire up his fishing boat for a tour of the bayou; most of the tribal members also work on or own shrimpers like the ones behind Dardar. Photo by Ian Gray.

Life in the accelerometer

This acceleration of loss fits what some are calling our current moment of existence—the “Great Acceleration.” Steffen et al, in a now heavily cited paper, use this metaphor to capture the global intensification of chemical, agricultural, industrial and infrastructural modes of production that happened after the Second World War.2 This intensification, they argue, is responsible for tipping the earth into the new geologic epoch of the Anthropocene. Looking at fifteen trendlines (such as population growth and water consumption or the presence of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere and the degradation of the terrestrial biosphere), they sketch a depressing, piece-meal portrait of the rapid and negative influence modern humans are having on natural systems around the globe.

Two trendlines Steffen et al do not sketch are those connected to the human-driven changes in natural sediment transport and the extraction of subsurface fluids from freshwater aquifers and fossil fuel reserves. The graphs would be equally startling. For instance, one comprehensive study of sediment transport estimates that humans currently move 63,000 million tons of earth per year, exceeding that of global oceans and rivers by a factor of three.3 Like Steffen et al’s trajectories, these displacements coincide with the large-scale use of combustion engines and heavy earth moving machinery—i.e. around the time of the Second World War. This leads the study’s authors to write that “The anthropogenic sedimentological record” provides yet “another marker on which to characterize the Anthropocene.”4

While their study captures an impressive measure of human planetary intervention, it grossly underestimates the full impact humans have on global soil mobility. In the absence of reliable data, they do not even attempt to calculate the “involuntary transport” of sediments via agricultural runoff and deforestation, nor the obstruction of sediments caused by dams, diversions, and flood control mechanisms. These anthropogenic interventions are likely responsible for an even greater disruption of the natural processes that shape the annual movements of earth.

Sunk Coasts

The land of Bayou Pointe-au-Chien suffers from the consequences of these various accelerations. Unintentional retention and channeling of sediment on the upper Mississippi prevents the natural replenishment of the soil in coastal zones.5 6 The extensive pumping of oil and gas from reservoirs just off the Louisiana coast speeds up land subsidence caused by the natural compaction of deltaic soils.7 And rising sea levels introduce more salinity into brackish ecosystems, weakening the plant communities of the salt marshes and making the land they hold together more and more susceptible to erosion.8

A skeletal row of dead oak trees—called rampikes—along Bayou Pointe-au-Chien; the soil has become saturated with saltwater, killing the trees from the roots up. Photo by Ian Gray.

By many measures, the land along the southern edge of Louisiana is disappearing faster than almost anywhere else on Earth. Since 1932, the State has lost nearly 2,000 square miles of earth. The current pace of loss is about an American football-field’s worth of land every 100 minutes. Or, a territory the size of Monaco, slipping beneath the waves every month.9 What can the State of Louisiana, a territorialized power, do in the face of a creeping, inexorable problem that is shrinking the size of its territory? That is taking away the property of some of its citizens? That is reducing the tax base upon which public expenditures such as flood protection or land restoration depend?

In coastal areas, there are two basic paradigms to dealing with these vulnerabilities: you can either help people move to higher ground—what is known in planner parlance as “managed retreat”—or you can try and fight these processes of acceleration. Stay put and counteract the land loss by “unsinking” the coast. For the moment, the state of Lousiana has chosen the latter option. And to do so, it has adopted an ambitious approach to coastal loss that we might call “outrunning the Anthropocene.”

The contestant in this race is a state agency, the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), or the Authority. Established after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the Authority set about consolidating and systematizing a hodge-podge of interventions designed to hold back flood waters and rebuild storm attenuating wetlands. This collection of interventions, called the CPRA’s Comprehensive Master Plan (2017), or the Plan, is the training manual for the race, whose duration is set for fifty years hence. The race’s winner, however, will not be determined by who crosses the finish line first. It will be won by answering a question of form: i.e. what shape will the coastline of Louisiana be in 2067? And given the rate of accelerating land loss, how much can human action control the shape of that line?

Accretion of logics, logics of accretion

The Plan calls for three principal types of interventions: structural, non-structural, and restorative works. Structural projects are the classic kind of engineered edifices that have shaped much of the modern approach to flooding on the Mississippi. The most significant of the structural projects is called Morganza-to-the-Gulf, an $8 billion levee system stretching along one-hundred miles of Louisiana’s southern coast. For the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, Morganza involves heightening its existing dikes from ten feet (good for resisting storm surge from the current 1-in-100 year hurricane) to between sixteen and twenty feet (high enough to ward off the more intense storm surges of the future). While the levees do nothing to counter land loss (and according to some research likely exacerbate it),10 exclusion from these upgrades would be detrimental to the Tribe. Not only do insufficient flood defenses exacerbate the immediate threat of the next storm event, but they also enhance the sense that these communities are being abandoned by the state. This in turn can cause insurers, banks, and other crucial services to withdraw, creating new forms of vulnerability for places like Pointe-au-Chien.

Part of the Morganza-to-the-Gulf levee upgrades include the recently built hurricane barrier on Bayou Pointe-au-Chien. The new hurricane gates are higher than the existing levees by a few feet (seen to the left of the photo); Mr. Donald considers that this is how the CPRA signals its commitment to increasing the height of the rest of the system—while also locking in the logic of levee construction as a means of protection. Photo by Ian Gray.

The Plan’s non-structural projects, meanwhile target risk-mitigation measures for individual buildings that exist in places where structural interventions are considered too expensive or ineffective. Floodwaters are to be accommodated either by flood proofing commercial buildings, elevating residential buildings, or, for homes considered too vulnerable, buying them from their owners. Out of over 26,000 structures identified for non-structural interventions in Terrebonne Parish, the vast majority are identified for elevations. Only 2,400 are targeted for potential acquisitions, indicating the Authority’s lack of appetite for supporting retreat.11

But among these different responses, it is really the coastal restoration work that lies at the crux of efforts to stem accelerating sediment loss. The restoration projects involve what we might call the Greater Acceleration—a state-managed effort to speed up the biological processes that cause land to accrete and grow. The goal, in other words, is to build back the earth faster than it is currently disappearing.

Restorations take the form of re-seeding marshes by dredging and/or pumping massive amounts of sediment from other parts of the river basin to the coast, rebuilding barrier islands through sand mining and transport, constructing artificial oyster beds on the bottom of coastal bays (oyster colonies help capture drifting sediment), and planting new, hardier species of land-retaining plants, such as non-native tropical black mangroves (whose growing range is migrating northward with changing temperatures).

Gulf waters near a planned salt marsh restoration site in Terrebone Parish have already inundated a road and the telephone poles planted along side of it. Photo by Ian Gray.

By far the most consequential and controversial of the Authority’s restoration work is what is known as a sediment diversion. To combat the loss of sediment caused by the Mississippi’s upstream system of levees, dikes, and flood barriers, the Plan calls for creating breaches—known as crevasses—in the system. These holes would theoretically allow the river, at designated points, to spill through human-built barriers and redistribute the soils that are currently dumped in the Gulf of Mexico back into coastal wetlands. One problem with the crevasses, however, is that by supplying coastal areas with more freshwater, they could change the salinity of saltmarshes and threaten sensitive shellfish and shrimp populations upon which local fisherman and their families, such as the Dardars, depend (hence the controversy).

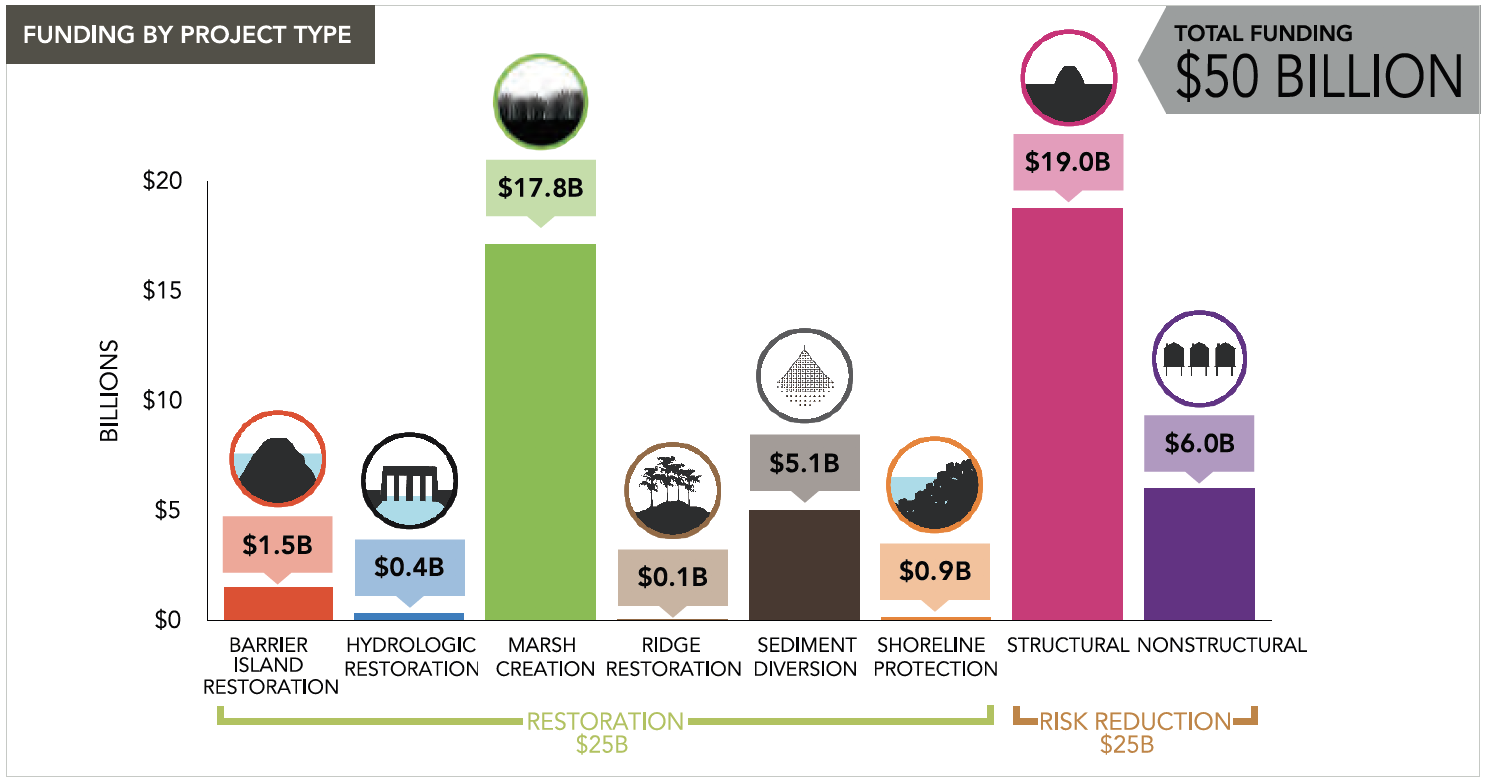

There are no designated sediment diversions near Pointe-au-Chien, but Mr. Donald takes me in his flat-bottomed fishing boat to an area in North Terrebonne Bay where the Authority would like to build 5,400 acres of marshland. Reconstructing these marshes will cost an estimated $299 million, yet it is not evident where funding will come from (nor how the marshes will be maintained as sea-level rise and subsidence continue to counteract reconstruction efforts). Of the $50 billion total expenditures projected by the Plan, roughly $19 billion are earmarked for structural interventions, $6 billion for non-structural risk reduction, and $25 billion for coastal restoration work.

Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) project funding categories. From CPRA Comprehensive Master Plan, 2017.

Currently, the bulk of financing for the Plan has come from a special disaster recovery fund set up with settlement money from British Petroleum after the company was found liable for the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Spill. But with only $8.7 billion in the fund, the BP money cannot cover everything. Local communities are shouldering some expenses—Terrebonne Parish has passed two sales tax measures, bonding $50 million and $100 million to assist in with the Morganza protections—but cash-strapped Parishes simply do not have the resources to meet the need.

Mapping the disappearance

The notion that the coast will no longer be livable, or that livability needs to be radically rethought, is anathema to many local residents in Louisiana. It is certainly not the kind of message that gets a politician elected. “Managed retreat” sounds defeatist. But “staying put” also needs to be understood in light of other imperatives of protection, like protecting the interests of corporations who operate along the coast, particularly those in the fossil fuel sector.12 Oil and gas production and chemical processing represent an enormous slice of Louisiana’s economy, but they also contribute to the emissions driving sea level rise, to land subsidence from pumped wells, and to the unraveling of coastal wetlands as hundreds of miles of dredged pipelines and shipping canals eat through bayou country.

On the ground, the changes in the land are often difficult to visualize. One year the marsh grasses are there, the next they are not. For Mr. Donald, however, the pipeline canals provide a way to measure the loss. A narrow canal dug when he was young has grown into a bayou size channel. “This happened in my time,” Mr. Donald says. “It’s the sea water that’s just eating away at the marsh grass, just making it disappear.”

Mr. Donald is frustrated about how little the state has done to enforce existing rules that normally require oil and gas companies to maintain their canals. “I try and get the state engineers to come do studies on this, or at least just come and fill these canals with rocks to block the sea water. I think it would stop the loss. It would be a start. But they never come.”

The Pointe-au-Chien community’s ongoing lack of federal recognition as a Tribe (something they have been seeking continuously since the 1980s), does not strengthen its hands in these kinds of negotiations. But holding oil and gas companies more accountable for the disappearing coasts is not something the Authority generally plans to do in any community.13 While most studies agree that the bulk of land loss comes from upstream flood controls that block sediment transport, research also points to correlations between the reduction in oil and gas extraction close to shore and decreases in local subsidence rates.14 And as far as understanding the impact of dredging on marsh health, the lack of knowledge suggests a significant need for more research, despite industry reluctance.

“We are a natural gas state”

The race to save the terre bonne of the bayous is on. Just a few days before I visited Mr. Donald in Pointe-au-Chien, Louisiana’s Democratic Governor, John Bel Edwards, was re-elected to his second term. While on the campaign trail he beat the drum for the state’s strategy of outrunning the Anthropocene: “We can no longer react,” he said at an event in southern Louisiana where he was announcing eight new coastal projects. “We have to be proactive. And that’s what coastal protection is all about.” A few breaths later, he was already undermining the chances for a successful contest, declaring, “There’s going to continue to be a demand for hydrocarbons for a long time to come… 20, 30, 40 years,” he said, adding, “We are a natural gas state.”15

The deep paradox at the heart of the Authority’s approach is that with fossil fuel extraction and emissions continuing apace, the speed of interventions will likely make a minimal dent in the expected loss. Actions taken in Louisiana are harbingers of the fundamental choices that public authorities around the globe will need to make—pour limited resources into protecting modes of production and consumption that exacerbate existing vulnerabilities, or start shifting public spending away from problematic activities toward different futures, and different relations with future landscapes. Envisioning these different futures will require rethinking liminality and what it means to live with water, rather than against it. These are lessons that frontline communities like the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe can already share, and which can help us reimagine a different politics of coastal protection and restoration for the Anthropocene.