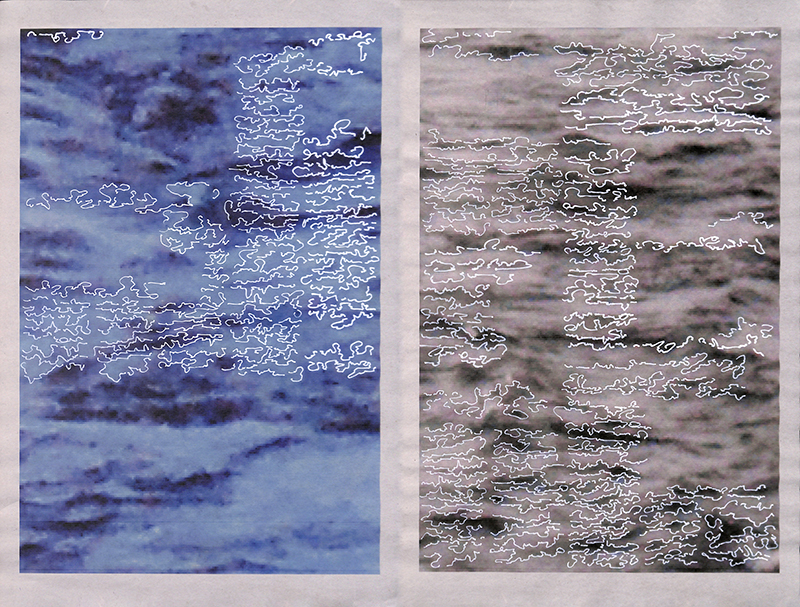

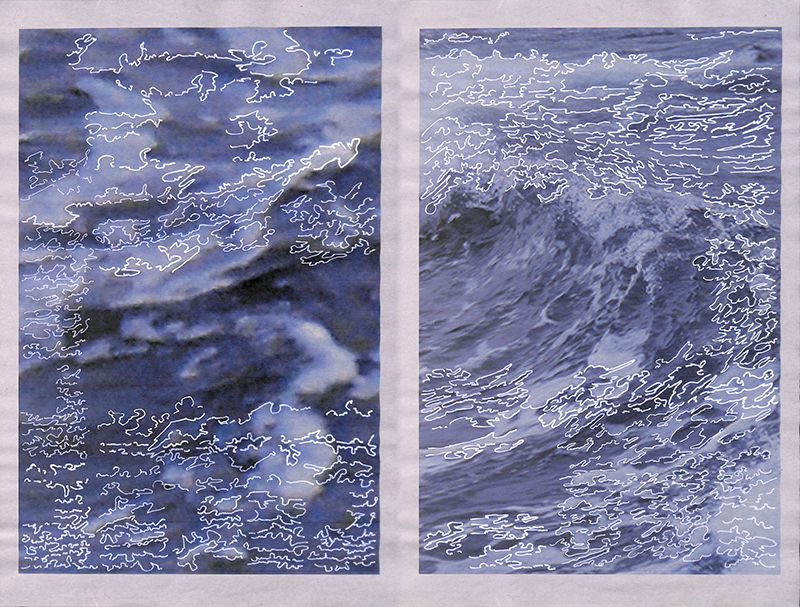

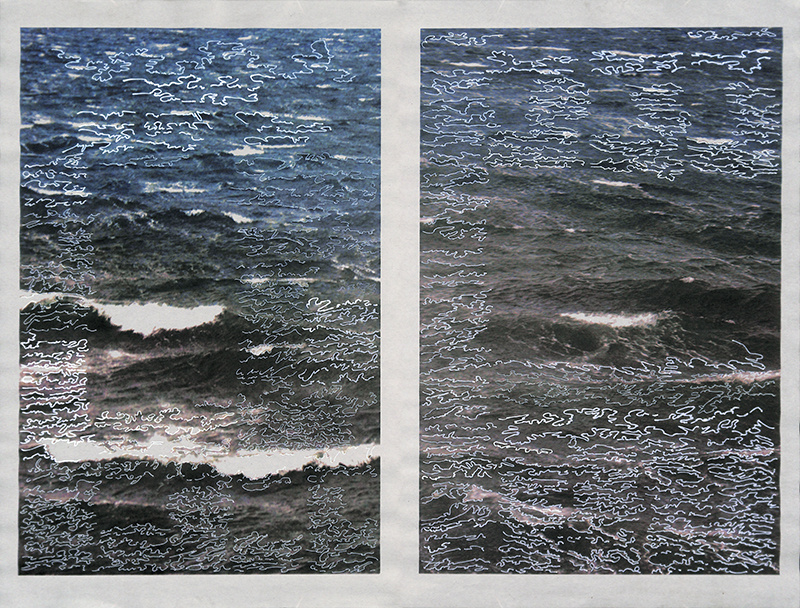

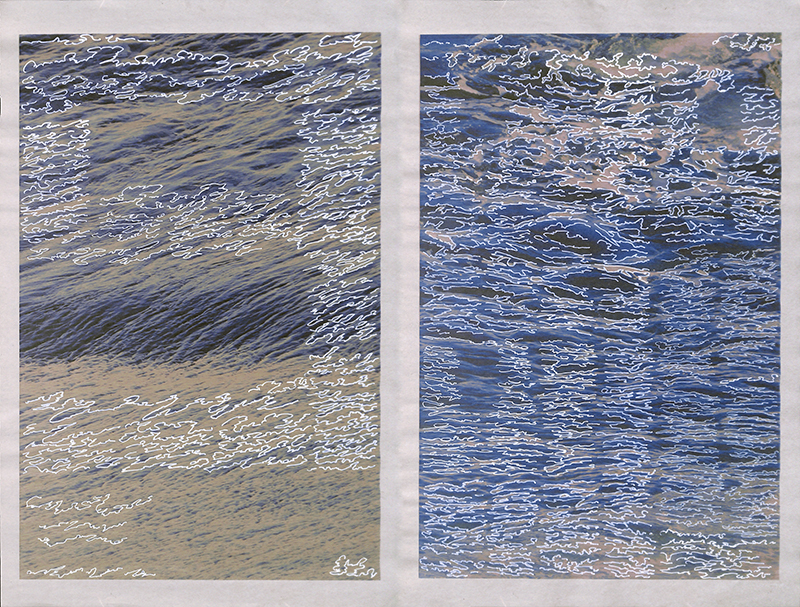

Newspaper Sketches of Ocean Waves

The Technosphere at the Edge of Globalization

This jointly written paper examines the place of cognition in relation to freedom and the globalization of knowledge. It looks at a specific case evoking Japanese‒English translingual encounters on the Pacific Ocean at the very beginning of globalization, from a Japanese point of view: that is, the end of the Edo period in the 1850s. The specific story recalls the first newspaper publisher in Japan, Joseph Heco, aka Hamada Hikozō, who, having been shipwrecked and rescued by American merchant seamen, misunderstood their English handwritten journal entries as drawings of ocean waves. The artist Toshiaki Hicosaka will discuss his recent artwork based on this anecdote. In response, the curator Eiko Honda will examine questions and possibilities that may unfold from the work in contemporary terms, by contextualizing them within the globalization of knowledge and social systems linked to the emerging notion of the technosphere. Thus, this paper is a result of Hicosaka and Honda’s ongoing dialog in relation to the artist’s latest artwork, created at the NES artist residency in Iceland, as well as Honda’s participation in the Anthropocene Campus 2016: The Technosphere Issue.

Toshiaki Hicosaka

The Kaigai Shimbun (Overseas Newspaper) was a newspaper in the Western style first published in Japan in June 1864 by the American Joseph Heco. Heco’s name in fact was originally Hamada Hicozō—he was a Japanese man born in Hyōgo prefecture. In the autumn of 1850, when he was thirteen years old, while on his way back from sightseeing in Edo, Heco’s ship was caught up in a storm and consequently he found himself shipwrecked and adrift on the Pacific Ocean.1 After about fifty days, he was rescued by the American merchant ship Auckland, arriving in San Francisco the same year. In 1850, Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the regime’s over 200-year Sakoku (National Seclusion), with highly controlled opening of its border. As a result, some of the other shipwrecked passengers who had returned to Japan were forced into confinement because they had “seen the world”; they were identified as Christian converts, and put under surveillance. Having discovered the situation in the homeland, Heco returned to Japan as an American interpreter for Kanagawa Prefecture Consulate in 1859—nine years after the shipwreck. It was another five years from this point before he began to publish the Kaigai Shimbun in 1864 by translating newspapers passed on to him by sailors who traveled across the sea.

Not only had Heco greatly sympathized with the idea of democracy while living in America, but he had also witnessed the “world” earlier than the majority of Japanese; he also entrusted the newspaper medium to spread the notion of democracy.

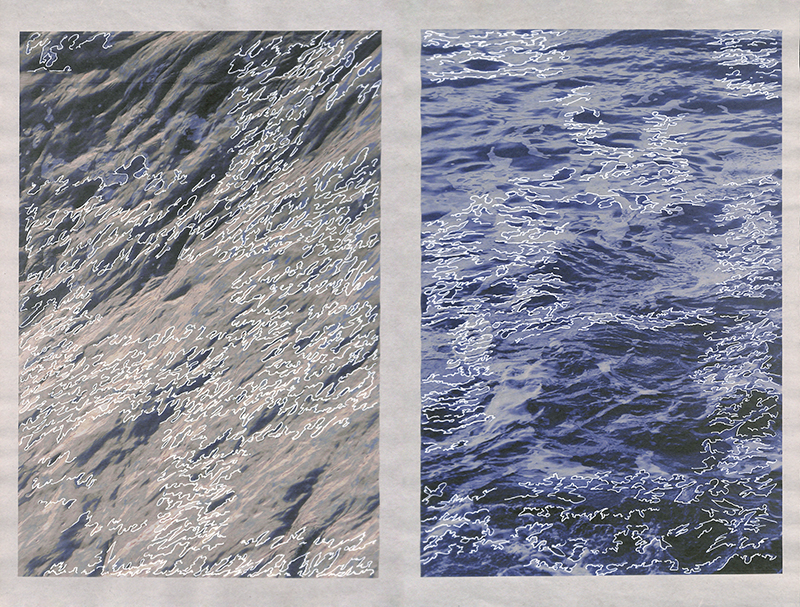

On the Auckland, the merchant ship that had rescued him, Heco had one particularly interesting experience. The location of the ship heading to San Francisco was, geographically speaking, a middle point that connected Japan with its foreign neighboring countries; it was also, on a symbolic level, a middle point of Heco’s process of experiencing the “world.” The people Heco encountered onboard the Auckland had an appearance altogether different to the Japanese and they communicated in an unknown language. Such lonely circumstances may have precipitated Heco looking inside one of the sailor’s diaries, where the continuous lines of cursive letters he mistook as the shape of waves moving up and down: in other words, “sketches of ocean waves.” How did this misunderstanding relieve his feeling of isolation onboard the ship? Perhaps the texture of the world shifted to a more positive one than the previous state. With my mind filled with this anecdote, consequently during my NES artist residency in Iceland in February and March 2016, I embarked on the project “Newspaper Sketches of Ocean Waves,” in order to re-enact this experience of misunderstanding.

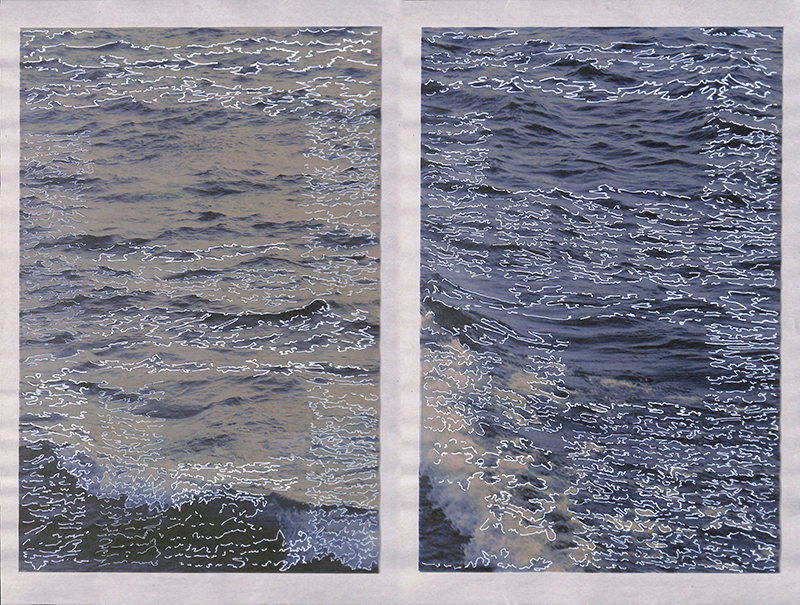

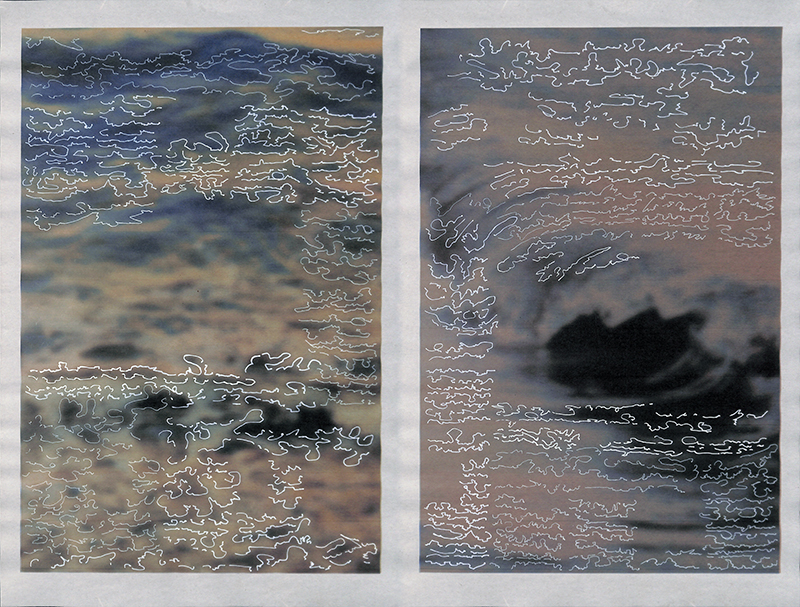

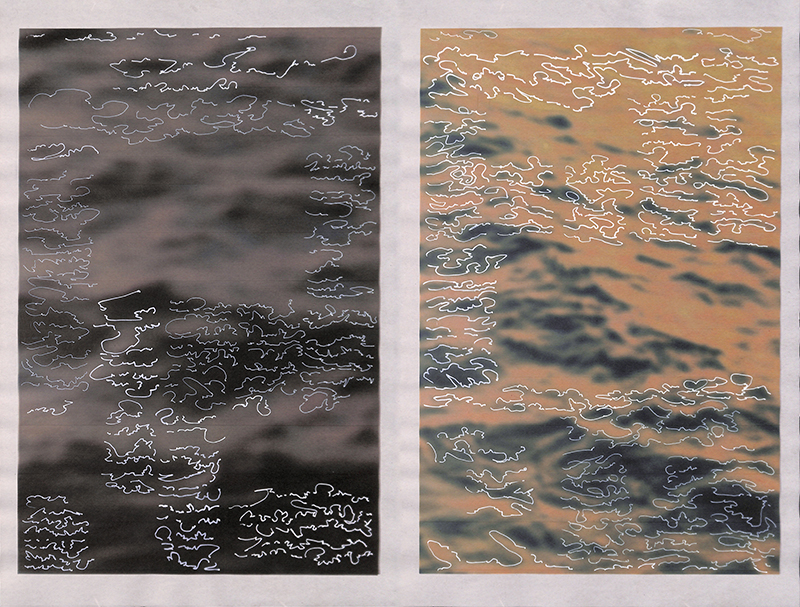

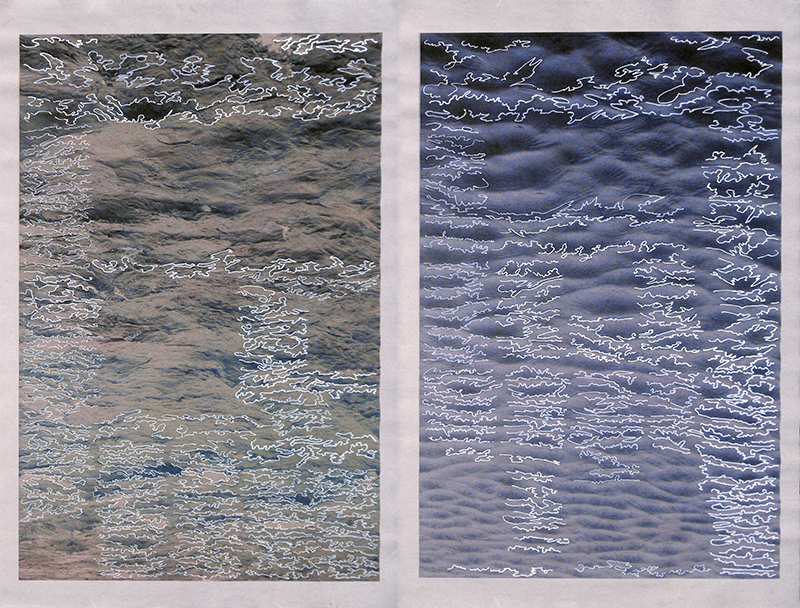

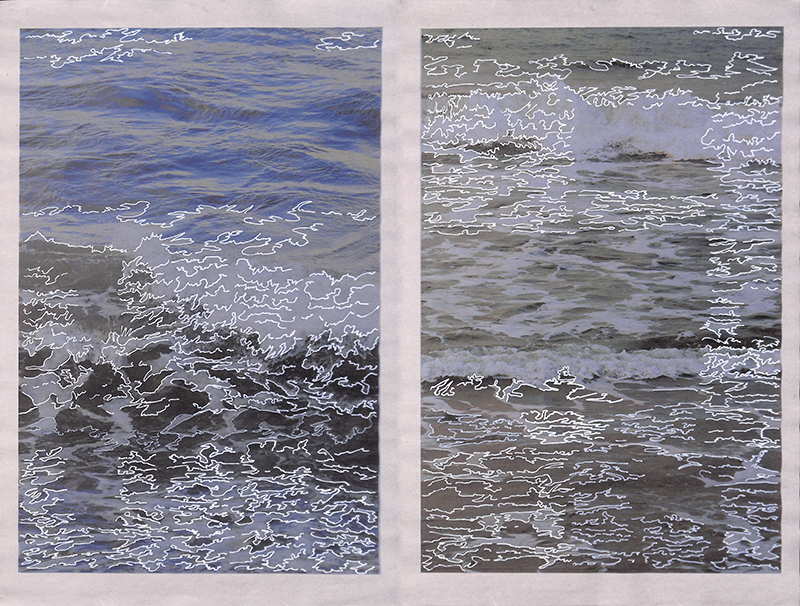

The process was as follows: I would take a photo of the ocean surface at the local beach, print it out on paper matching the size of the local newspaper, and make a drawing with a white pen on top of it. The drawing would reference the layout of both the photos and words on the local newspaper published each day, and I would publish my work every day during the residency period as “Newspaper Sketches of Ocean Waves.” I would then overlay the newspaper and print out the images of the ocean one on top of the other, and gradually draw a line against the areas of printed words as if I was writing a sentence with cursive letters. I set a rule, whereby I would try not to forget to trace the shape of the ocean waves that remained on the photograph of the ocean surface as I moved the tip of a pen. In other words, the line would be drawn while my consciousness was suspended mid-air between my attention to writing words (i.e. the movement of my hand) and attention to tracing the ocean waves (i.e. also a hand movement). If I leant too far toward one side of this consciousness, I found that the line I drew became too lively and very poor. The difficulty of drawing without being partial to one or other of these two types of focus—of maintaining balance, of keeping my consciousness in mid-air—is similar to the way in which it is difficult for one’s body and its perceptions to avoid automatically imposing its own pre-existing ideas or understandings on everything encountered. I published the drawing I attempted thus as a different kind of newspaper each day. Newspapers usually take on the role of naming and fixing “actuality” (i.e. reporting on what is happening) in society locally, nationally, or internationally. However, with this project, I tried to consider an alternative possibility for the medium by publishing the enacted experience of Heco as my personal experience—a trace embedded in a reality of an individual—as a different sort of ambiguous information in newspaper form.

Eiko Honda

Toshiaki Hicosaka’s “Newspaper Sketches of Ocean Waves” (2016) invites viewers to gravitate toward an undefined cognitive space that exists beyond the identifiable lines of ocean waves and cursive letters, by resisting our temptation to instantaneously identify the visual appearance (i.e. the ocean waves or words) as a clear representation of the knowledge we already have. Now, what does it mean to pause over such an invitation in our globalizing world? What does it mean to re-enact the particular experience of an individual in our current context: is it as a work of contemporary aesthetics?

Perhaps let us begin by looking at the historical context then and referencing it to the now in relation to the phenomena of globalization—namely, the globalization of knowledge and of social systems. For Heco in 1850 the experience was a leap beyond the boundaries of his recognizable world—beyond recognition of his scope of knowledge. Importantly, Heco accidentally took this leap more than a decade earlier than most people in Japan did when the country officially widened its restricted border at the beginning of a rapid globalization process at the end of the Edo period (from 1863 onwards). The trigger for this microlevel of globalization Heco experienced was an external force, a collision of two systems of passage particular to the geo-locality of the Pacific Ocean: one is the passage of the climate driven by the windstorm, and another is the passage of human movement driven by America’s international trading aspirations. In other words, Heco’s cognitive horizon was expanded and directed, not determined, by systematic factors, as these were greater than any control he had over them.

Yet at the same time, Heco’s temporal liberation from this greater system can be observed from Hicosaka’s discussion: at the instant of recognizing the handwriting as sketches of ocean waves, and perhaps realizing later that this was not what they represented, Heco collided with a new system of knowledge, namely English, which he had not recognized before. It is therefore possible that on one level Heco’s eyes were opened to a knowledge system different to that with which he was familiar, and, on another level, that his misunderstanding also inhabited a space beyond the existing systems of knowledge. Hicosaka suggests, therefore, that this is a space of freedom, which was flourishing in Heco’s mind in the transitional process of transcultural cognition.

The collision of various knowledge and social systems since these early days has accelerated across the globe under the term globalization, increasingly penetrating the ways in which individuals live and inhabit the world. One of the driving forces behind this could be described in terms of what the geophysicist Peter Haff proposed in 2014 as the “technosphere.” Haff claims that a sphere, like a biosphere, could be identified as the “technosphere”—a system that produces “the workings of modern humanity.” According to Haff, this sphere “operates beyond our control and […] imposes its own requirements on human behaviour.”2 Importantly, this system was not under any overall governance nor was it designed by a centralized power during its emergence.3 Instead, it has gradually developed through enmeshed layers of various social systems, which have evolved through the simultaneously occurring sequence of what the complex systems scientist Jessica C. Flack and the theoretical biologist Manfred D. Laubichler call a “reactive social engineering,” and where “attempts at social control have been mostly reactive responses to the consequences of previous actions and decisions.”4 Insofar as systems of knowledge and society are engineered reactively, with an attempt to temporarily resolve problems—i.e. the unintended consequence of previous decisions—our human reliance on such a sphere will be likely to continue to expand.

Within these circumstances in 2016, there would be no end to the eye-opening situations to other systems of knowledge, such as the one Heco himself embodied in 1850. Yet, the only kinds of informational knowledge perceivable may typically be the kinds made visible by the technosphere: the kind of knowledge that Hicosaka terms the “actuality” of society—created, for example, by the medium of a newspaper. Yet, should we feel inclined to seek consciously and then embrace the undefined cognitive space, what will we find? The “reality” proposed by Hicosaka in his alternative newspaper—the space beyond the identifiable lines of ocean waves and of cursive letters—is the space of consciousness that is yet to be penetrated either by the technosphere or established systems of knowledge. It is here that we might find an experiential knowledge of freedom, just as Heco did, even if it is only momentary.

Hicosaka and Honda: Further Enquiries

Although not directly discussed here, our developing dialog over Hicosaka’s artwork also brought us to the question of democracy. Finding the notion of democracy inspirational, we wondered where Heco stood in relation to this political idea and whether his “Overseas Newspaper” revealed insight. Was the idea “overseas” that as represented by America where he lived? Could the medium of the newspaper still carry a hope for democracy in our time? How could we employ the tension that exists between “actuality” and “reality,” which Hicosaka proposes in his work, in relation to the idea of democracy? Is democracy possible on the Earth where/if the autonomous technosphere constitutes the totality of life and experience on the planet? Whose democracy is it after all? Is the space of “freedom,” toward which Hicosaka invites viewers to gravitate their consciousness, a possibility for anarchy? We did not initially envisage addressing these lines of inquiry, but we look forward to expanding on them in due course.