Meeker Dam

Bruce Braun draws upon the hauntological qualities of a post-industrial, Mississippi ghost: Meeker Dam, Minneapolis, taking the now largely underwater ruin as a lens through which to examine other histories—and presents—long-submerged: the dispossession of land and denial of indigenous sovereignty as a result of settler colonialism.

Submerged ruins of Meeker Dam. Photo by Steven J. Dunlop.

If you walk south from the Franklin Bridge in Minneapolis along the east bank of the Mississippi, you can pick up a rough trail that takes you under the towering Short Line Bridge, past stormwater outlets, to a small historic park. Here, if you are fortunate, you might see the remains of a long-forgotten lock and dam. I say “fortunate” because the dam is a ghostly presence. Completed in 1907, abandoned and largely destroyed in 1912, its remains lurk just beneath the surface. When water levels fall, often toward the end of summer, it seems to rise from the river, an apparition that disappears just as silently as it arrived.

“Ghostly” may be the wrong term. Or, if it is to be the right term, we will have to understand better what it is that returns. For ghosts return; they haunt. They must be attended to, be come to terms with. Which is to say that the Meeker Dam, as it is commonly known, is not just a ruin that occasionally presents itself to those who walk along the river’s shore or to those who descend the recently restored wagon road from St. Paul, restored not long after the dam was placed on the National Registry of Historical Places in 2003. Nor is it merely a quaint reminder of the engineering feats of settlers or a charming remnant from past struggles between Minneapolis and St. Paul—mediated far away in Washington D.C.—over which city could rightly claim to be the head of navigation on the river.1

Rather, it represents the historical emergence of a new paradigm, a particular way of thinking about the Mississippi and its social and political futures, one that remains submerged in settler consciousness today, in the same way that the dam is submerged in the river—as an absent presence that we see only poorly, refracted from beneath the surface of a now-placid river. For the Meeker Dam represents a settler vision and a settler spatiotemporality: the river imagined and remade as infrastructure on which the development of a settler society and the fortunes of an emerging industrial capitalism would rest. This is a vision that turns the river into a problem of engineering, fluid-mechanics, geology, and hydrology. It makes of it a puzzle to be solved: how to channel water, hold it back, let it flow at the right times and through the right spaces; how to move boats up a river that is too shallow, its drop too steep; how to regulate flows so that commodities can be moved to markets, investments realized, speculations in land made profitable. The river was remade within a spatiotemporal imagination that linked northern forests and farmer fields to distant markets that no logger or farmer had ever seen.

Yet, if the remains of the Meeker Dam haunt us, it is perhaps for other reasons. For when the Meeker Dam was first proposed in 1852, the ink on the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux2 had not yet dried, the Dakota Uprising was still a decade in the future, and the concentration camps established in the winter of 1862/63 at the confluence of Mnisóta Wakpá and Ȟaȟáwakpa—a sacred site for the Dakota—existed only as a latent potential within the violent expansion of settler colonialism. The Meeker Dam haunts us for what it embodies. Not just as the projection of an infrastructural vision, but the projection of such a vision when other territorialities, temporalities, and ontologies—Dakota, Ho-Chunk, and Anishinaabe—were present all around. Rising from its watery grave, the Meeker Dam forces us to ask what made it possible to imagine the river then as an industrial river, part of an emerging industrial capitalism that had only recently taken hold further to the east? What erasures were necessary, what ontologies, territorialities, and temporalities had to be willfully ignored, for the river to become the “nation’s river,” subsumed within the taken-for-granted temporalities of a settler nation and its political and legal institutions? How was a settler futurity set in place and Indigenous futures rendered unimaginable? And what might it mean to reflect on this moment today, when the future of the river is again in play?

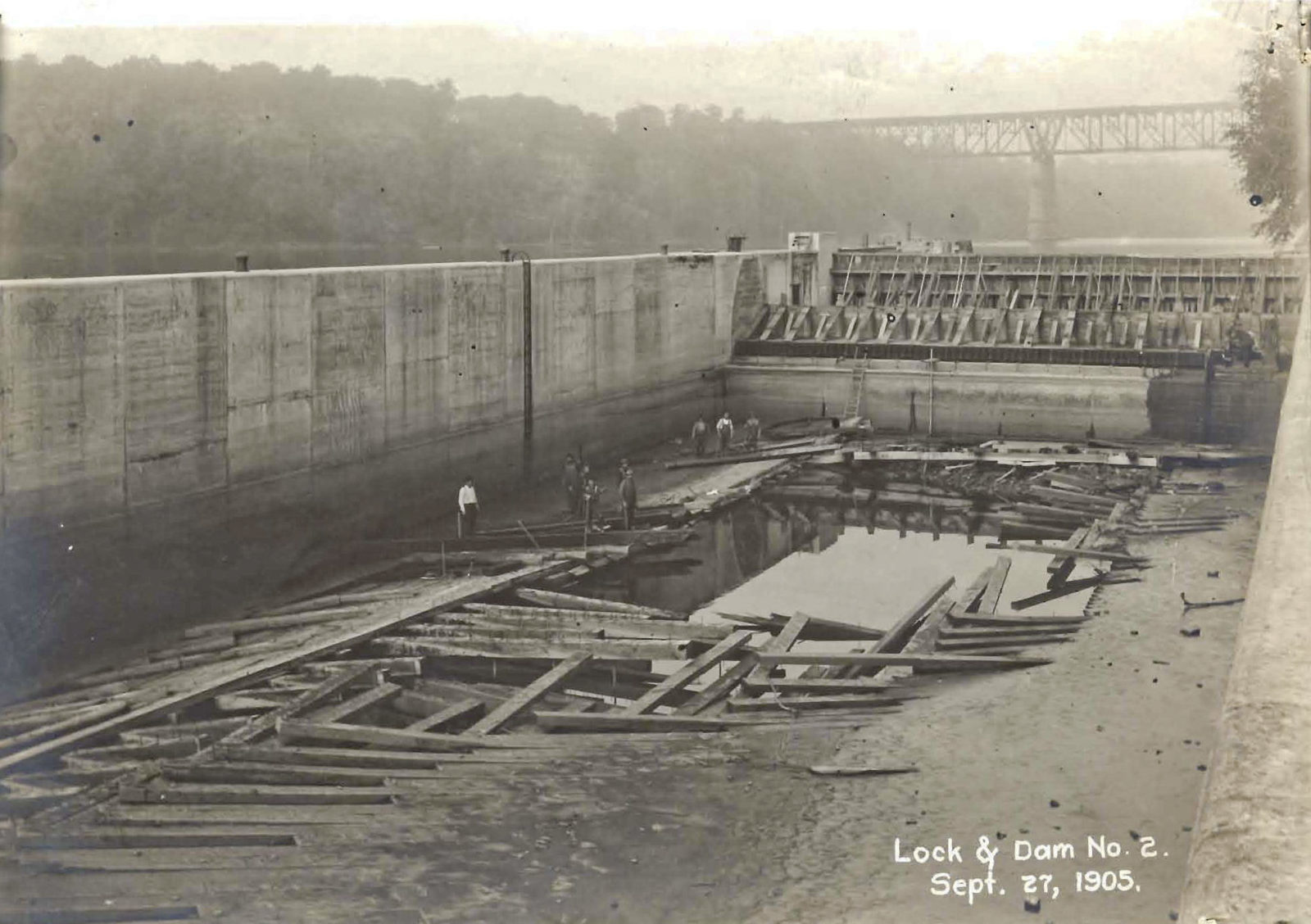

Meeker Lock and Dam under construction Sept. 27, 1905. Photo by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

I am drawn to this site because it requires me to consider what remains in and what returns from the past. The dam was abandoned in 1912 because a much larger dam—what is now known as Lock and Dam No. 1—was built a few miles downstream, large enough to allow for navigation upriver to just below St. Anthony Falls, and with sufficient head to generate energy for the Ford Motors assembly plant that relocated there in 1925. In the following decades, almost 30 locks and dams would be built on the Upper Mississippi. Together with levees and dredging to control floods and enable larger barges, they produced an engineered river linked to industry and agriculture from Minneapolis all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, one which conformed to a geopolitical imagination that had no place for, or even consideration of, other temporalities and territorialities, other relations to water and land that did not follow the logic of settler law and property.3 Today, managed as an integrated system, the locks and dams capture and channel the energy of water toward particular ends rather than others, creating new social and ecological relations, subtending settler society and its industrial ecologies, and, in their day-to-day operations, obscuring and continuing the work of dispossession, oblivious to those or that which have been displaced. Indeed, what remains of the Meeker Dam is less the physical ruins of the dam itself than a political, economic, and ecological rationality that presupposes nation and state, one that imagines capitalist markets to be as natural as rivers, and one that projects and assumes a settler future as a matter of course, much as Meeker and his associates already did 167 years ago.

The story of the Meeker Dam is thus not just about a dam and a river, but a world created around it, a bustling city built on the fruits of primitive accumulation and the depletion and degradation of northern forests, soils, and water. As residents of the Twin Cities, we inherit this river and its worlds, albeit in radically different and unequal ways. During periods of low water, when the Meeker Dam appears to rise from its watery grave, it reminds us that the urban worlds we take for granted are built upon and carry forward these settler temporalities, spatialities, and ecologies.

But what does it mean to say that we inherit the Meeker Dam, when this “we” is defined by the benefits derived from Indigenous dispossession? What responsibilities does this demand? We might begin by noting that benefits are derived unevenly, that in the context of forced migration, immigrant exclusion, relocation, and chattel slavery, not all non-Indigenous residents are settlers in the same way.4 We might continue, as Potawatomi scholar Kyle Whyte proposes, by refusing to deny that as settlers, we live in what our ancestors could have only seen as fantasy times. Whyte notes that for centuries, European colonists and settlers were unable to dominate the Native alliances in the region, and “would have relished the very idea that they could advance whatever business interests they wanted without facing threats of empowered resistance and diplomacy. They would have delighted in the idea that their legal orders would not have had to bend to or accommodate Indigenous legal orders.”5 Even for Meeker, confidently projecting a future of river commerce and white settlement, the world we inhabit today would have seemed a fictional utopia. Dakota resistance had not ended and would only become more vigorous. Settler law and property were far from settled, and the river did not bend easily to the desires of investors and engineers. When construction of Meeker’s dam was finally begun, long after Meeker himself was dead, engineers struggled to control the force of the river, resulting in cycles of destruction, redesign, and repair. Whyte asks us to see our present as continuous with this past, indeed, founded on it. Borrowing his language, we might say that infrastructures built in the past “were constructed to provide privileges to the builder’s descendants. They were gifts of a troubling sort.”6 Draw up a list of Minnesota’s Fortune 500 companies, its many co-ops, or its public institutions like the University of Minnesota, where I teach and write, perched above the river gorge. Built on past and present dispossession, these institutions—private, cooperative, and public alike—presuppose and often extend the displacements of settler law and violence, quietly folding past appropriations into the present, benefitting from the “natural” workings of property and market and the infrastructural and institutional environments that today appear as nothing more than sites and effects of “good governance.”

This is what Whyte asks us to consider. If the Meeker Dam haunts, it is not only because it reminds us about a past where the future was not assured, but because when it rises from its watery grave, it brings that past into the present, it reminds us that if we look beneath the surface and allow ourselves to see what remains, we see that we are still fully within this history as an ongoing process. The Meeker Dam is (in) our present.7

Today, as the US Army Corps of Engineers considers the disposition of the locks and dams in the Twin Cities, and as proposals to “rewild” the river gain traction, we do well to reflect on what remains and what returns from this past. But it is also critical that as settlers we refuse to assign Indigenous sovereignty and resistance to the past. As Jean O’Brien, scholar of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe, notes, the view that settler colonialism has an eliminatory nature may be correct, but it problematically “pulls toward the notion of extinction,” when what is needed is an understanding of “the continuance and survival of Indigenous sovereignty.”8 Just as Dakota resistance had not ended when Meeker proposed his dam, it has not ended today. Whether through the construction of the Bdote Memory Map, the work of the Healing Place Collaborative, demands to remove Sam Durant’s gallows sculpture from the Walker Art Center’s sculpture garden, the insistence on remembering Indigenous sites like Spirit Island, or the work of Water Protectors along the route of the Line 3 pipeline in Northern Minnesota, Indigenous futurities are multiple and exist in the now, while settler futures are not as assured as they may seem.

Perhaps this is what the ruins of the Meeker Dam surface tell us: not only that we inherit its troubling gift, albeit in different ways, but that the river we inherit—this Anthropocene River that is also a settler-colonial river—is not the only river or the last river. Other rivers, other sovereignties, other futures are already here, have been all along, and are still to be invented.

Sources

John Anfinson, “The Secret History of the Mississippi’s Earliest Locks and Dams,” Minnesota History, vol. 54, no. 6 (1998): pp. 254–67.

Iyko Day, “Being or Nothingness: Indigeneity, Antiblackness, and Settler Colonial Critique,” Critical Ethnic Studies, vol. 1, no. 2 (2015): pp. 102–21.

Jean O’Brien, “Tracing Settler Colonialism’s Eliminatory Logic in Traces of History,” American Quarterly, vol. 69, no. 2 (2017): pp. 249–55.

Audra Simpson, “The State is a Man: Theresa Spence, Loretta Saunders and the Gender of Settler Sovereignty,” Theory & Event, vol. 19, no. 4 (2016).

The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux of 1851

US Department of Interior, National Park Service, 2003, “National register of historic places registration form. OMB No. 1024-0018. Lock and Dam No. 2.”

Kyle Whyte, “Indigenous Science (Fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral Dystopias and Fantasies of Climate Change Crises,” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, vol. 1, no. 1–2 (2018): pp. 224–42.