Driving the Limits of Time

Clashing Temporalities seminar reflection

In this reflection upon the Clashing Temporalities seminar that took place as part of the Anthropocene River Campus, Thomas Turnbull considers the non-fixedness of the concepts of time and place that represented its core concerns. From a fishing township in the Atchafalaya basin that has seen the ecosystems it has relied upon for generations change at an alarming pace, to the mis-memorialization of history and omission of the stories of those who were enslaved at a former plantation, to a scientific model of the river that both chronicled a past and focused upon a future narrative centered around human control, the seminar evidenced the troubling myriad of temporal clashes at play in the region. But acknowledgment of and engagement with these complex clashes, the author writes, offers opportunities for generating coherent responses to the seemingly totalizing notion of the Anthropocene.

Where do you stand? Simple questions can be the hardest to answer. In advance of opening the Anthropocene River Campus in New Orleans, organizers of the seminar “Clashing Temporalities” asked participants to think very deeply about where they were. With a little reflection, it becomes clear that, the deeper you think about where you are, what first appears as a fixed substrate, firm and solid beneath one’s feet, can—with a little imagination—become dynamic once more. Particularly when we let our perspectives extend beyond the diurnal and mediatic temporalities that govern our everyday lives, past the overheated pulses of human history, and, further still, into the fathomlessness of geological time.

In response to our request, we received a number of accounts of terrestrial situatedness that attested to both the imagination and the geographic reach of our participants. A townhouse in Troy, New York, whose foundations rest on lead-poisoned soil. Someone’s hometown near Pliocene ravines in the Argentinian Pampas, formed over 2.5 million years ago. An account of the Alpine-Carpathian Basin, where the city of Vienna lies and whose oil fueled National Socialism. A newly purchased marital home in South Africa atop granite rocks formed when waters receded from the Cape Flats of Gondwanaland. The unglaciated topography of the Midwestern Driftless Area. An archaeological site south of Chiang Mai, Thailand, resting on the Shan-Thai Terrane tectonic plate. The attic study of the secretary of the Anthropocene Working Group, built on Mercia Mudstone clay, remnants of the shallow saline lakes of the Pangean supercontinent, back when the United Kingdom lay twenty to thirty degrees north of the equator. Most of our participants from New Orleans noted a more immediate plasticity to their surroundings. Their feet rested on thick and fairly recently deposited alluvial sediment, a shifting morass that means the city is, as one resident later told me, “like a concrete lily pad floating on a pond.”

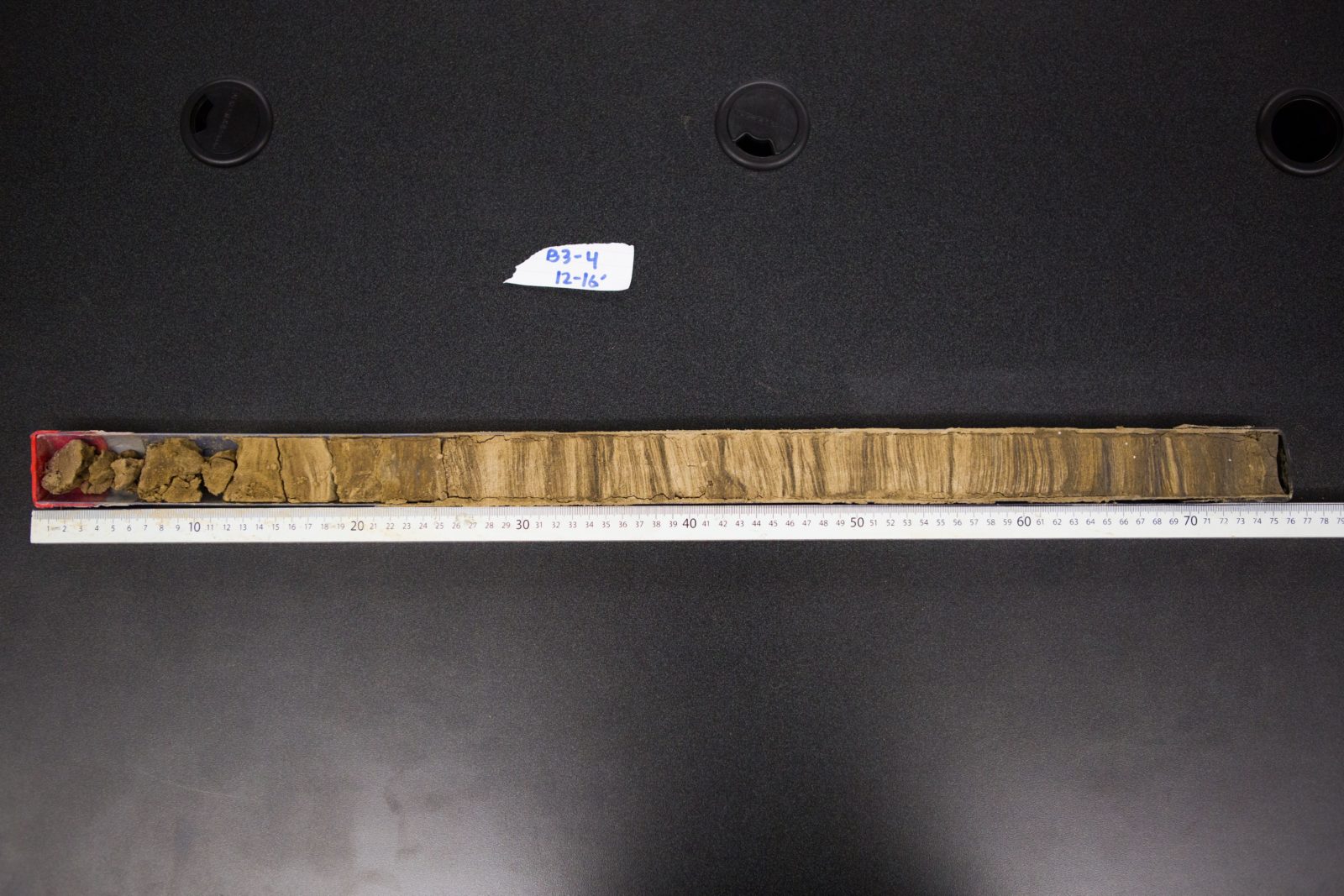

A number of tools are available to interrogate the temporality of where we stand. These range from human memory and shared anecdotes to songs and stories, and the carefully archived records of powerful institutions. Geologists possess a unique apparatus for such time travel. With something akin to an apple corer, driven vertically into Earth’s surface, they can extract an excerpt of planetary time. These “cores” are a record of the seemingly chaotic processes of erosion, weathering, and hydrology that are set in motion by earthly processes. When the sediment these processes create relents to gravity, it forms layers, and so within our corer lies a tube of matter, a punctiform snapshot of areal sheets. Such cores, in the words of marine biologist Rachel Carson, offer “a sort of epic poem of the earth.”1 Their order, width, and composition—or laminations—register major and minor shifts in telluric keys. Cataloging present surface to deep past, cores can reveal myriad changes, from that of local farming practices to global climate, insofar as such change can register in the chemical composition of the core or in the pattern and spacing of its layers. The “Clashing Temporalities” seminar was intended to consider the relation between all kinds of temporal registers, to see how geological, historical, rhythmic, and experiential time fold in on one another. Our aim was to come to a better understanding of the indivisibility of time into human and nonhuman scales, and to trace the causal relations between past and present that have contributed to the strange concatenation of human and Earth history we now find ourselves in.

In planning the seminar, using a now ubiquitous video-conferencing software, it was clear that negotiation and compromise would be necessary. Each person organizing the session came from a different place and a different school of thought. A professor of coastal and urban estuaries, a polymath naturalist musician, a sedimentologist, and a historical geographer. Bridging time zones to reach one another, it became clear that differences in situatedness, scientific training, beliefs, life experience, and opinion would lead, if not to clashing personalities, then to clashing expectations as to who and what forms of testimony were essential to communicate the significance of the sites we would encounter. Minor disputes over content, partners, location, timings, and involvement were, to everyone’s credit, resolved with sensitivity and kindness. The outcome of these discussions, I think, demonstrated that clashes can be generative, resolvable, and, in the run of things, can allow for a better appreciation of one another’s positions and the constraints and achievements by which perspectives are formed. We proved that song can be of geoscientific significance, providing an emotive record of the waves of cultural history that have impacted upon the Earth, and that meditating on a core sample—an exercise in temporal mind expansion—can offer its own inspiring resonances.

On the first day of the Anthropocene River Campus, we boarded our time machine on McAlister Drive, just beyond Tulane University. In scenes reminiscent of school trips of yore, roll call was taken and po’boy sandwiches and cookies stored in overhead lockers. After days of intense meetings in air-conditioned auditoriums, it was refreshing to head out of the city, west along the sinuous Highway 18, the old River Road. For some, this was the first time they had laid eyes on the Mississippi River, and our local conveners, Bruce Sunpie Barnes and Amy Lesen, pointed out the almost absurdly illustrative sites as we passed by: from simple houseboats, which, like the state’s refineries, exist in regulatory niches that allow their owners to subvert taxation, in this case by risking life on the water, to cropped sugarcane, whose remaining bagasse burnt like a fuse across neat, rectangular fields, its smoke adding an acrid note to the recycled air of the bus.

As we moved onward, Amy and Bruce shared their wide-ranging expertise over the crackly intercom, guiding us through an environment in which the past and present concerns many of us had only read about were very real. As Amy noted, this region is less a still life than a dynamic “cascading series of events.” Our route traced permeable interfaces between industrial archaeology and hydrogeography. We passed the Bonnet Carré Spillway, a vast sluice that controls the river’s flow into the brackish Lake Pontchartrain. Amy told us that this mechanism had required more regular operation in a period of unprecedented rainfall. In fact an estuary rather than a lake, Pontchartrain’s incursion into the surrounding lands can be plotted by the waiflike cypresses that have succumbed to the salinity of its waters. A more constant companion were the concrete and turf-clad levees, which, at twenty feet high, persistently obscure the river. To a well-trained eye, surface traces of subterranean pipelines could also be discerned here and there, furtively channeling hydrocarbons through thick and unstable mud.

With considerable skill, our driver negotiated the narrow roads of the township of Pierre Part, in Assumption Parish. Our bus, scraped by the low-hanging branches of live oaks, came to a stop, and we poured out. It was an absurd entrance into this thick-aired site of backyard domesticity. Artists, academics, and concerned citizens from around the world had arrived at the home of a welcoming, if somewhat bemused, family. Thanks to Bruce, we were there by invitation. We were greeted by eighty-two-year-old fisherman Mr. Daigle, whose home it was, as well as his son Kevin and a cast of other family members and curious neighbors. The Diagles are Acadian, descendants of French-speaking people from Atlantic Canada who the British forcefully deported from that region in the 1700s.2 Mr. Diagles’ home is raised on blocks. It backs on to a dense swamp, a silty interconnection between a series of lakes from which subsistence and income have been derived for generations. Mr. Diagle, seemingly amused by our arrival, immediately won our crowd over by assuring us he was “not a Trump man.” Settled in his porch chair, he told us of the changes in the number and distribution of animals from which he had made his living: catfish, nutria (swamp rats), crawfish, turtles, and alligator. His great familiarity with the life cycles of these creatures and his firsthand experience of working this watery land have directly shown he and his family how changes in mean global temperature have affected their immediate environment and the prospects of deriving a living from it; put succinctly by Vivian, a resident of Pierre Part, “the seasons are messed up now.”

Mr Diagle, his son Kevin, and Bruce Sunpie Barnes on the porch of the Diagle Family Home, Pierre Part, Atchafalaya Basin. Photo by Neli Wagner

The Diagles’ family home lies in the Atchafalaya Basin, a watershed through which only a denuded branch of the Mississippi now runs. The majority of the Lower Mississippi’s flow has long been diverted by the upriver Old River Control Complex, a towering dam that divvies up the channel and protects against flooding during periods of high water. The diversion of the river, which begun in the early nineteenth century, helps to maintain the wetland we found ourselves in, and contributes to the stabilization of communities such as Pierre Part. But any sense of calm can be shaken off by learning a little of the river’s history. Its main branch, the Atchafalaya Basin bypass, is due to avulse, that is, to shift its path. This avulsion will occur when the 150 million tons of sediment that pass through the river each year sculpt a new path of least resistance through the landscape’s topography. The last time this happened was around 2,000 years ago. A shift is long overdue, and humans may be helping to induce it. Increased rainfall, partly fueled by the accumulated effects of fossil fuel use, requires upriver floodgates such as the Old River Control Complex to be opened with greater frequency to protect downriver cities, particularly New Orleans. More frequent inundation of the upper reaches of the Atchafalaya is a gamble—a depositional crapshoot that risks causing the Mississippi bypass to turn west and course though the Atchafalaya Basin, potentially destroying and certainly transforming communities such as Pierre Part. 3With this fragility in our minds, and seeking to show our appreciation to the Diagles, Bruce adopted the distinct vocal pitch required for a series of Cajun songs and played us out on his accordion.

Cypress swamp behind the Diagle Home, Pierre Part, Atchafalaya Basin. Photo by Neli Wagner

We turned on to the Old River Road but our journey turned backward into deep geological time. Sitting up front with the microphone was research geologist and paleobotanist Scott Wing, a member of the Anthropocene Working Group. He has family in nearby Morgan City, and he took the opportunity to combine his concern for the region with his scientific training, giving us insight into the long history of hydrocarbon formation in this place. The majority of Louisiana’s petroleum began its formation during the Mesozoic era, over 180 million years ago. As the continent’s largest watershed, the geomorphological precursors to the Mississippi River Basin acted as vast catchall for accumulating organic matter. Organisms such as algae and plankton were drawn into the river’s flow, forming thick mats of biological matter at the mouth of what is now the Gulf of Mexico.

These batteries of decaying compounds were slowly inundated with layers of sediment—a slow burial in a geological pressure cooker. Such was the pressure exerted that the Earth’s crust bowed and subsided. The heat this process generated slowly altered the chemical structure of the entombed organic matter, cracking the former fruits of photosynthesis into reservoirs of liquid hydrocarbons topped by lighter gas fractions. Alongside the state of Louisiana’s lax regulatory regime, it is this slow motion geological circumstance that partly explains the profusion of petrochemical plants that cluster in Louisiana. With a constant procession of refineries and sulfur piles passing by our now bug-splattered windows, the toll that our pact with long-fossilized biota is exacting was clear. This unlikely sequence of Earthly events found its way into, among other things, the pistons of our bus’s six-cylinder combustion engine. There, carbon became heat, and heat the motion pushing us onward. We hydrocarbon-propelled planetarians were left to reflect on Scott’s point that “everything is really connected to everything else, on short timescales and over many millions of years.”

Refinery Complex, River Road, Louisiana. Photo by Sarrah Danziger

After driving back along a section of the River Road, we arrived at the Laura Plantation. The site sells itself as “Louisiana’s Creole Heritage Site.” Our local conveners explained that our destination was one of the better examples of the commodification of plantation history that dot this stretch of road. As journalist Nygel Turner has elsewhere explained, such places present a misleadingly genteel version of “big house” life, where mint juleps are sold under trees festooned with Spanish moss.4

Whatever its relative merits, the Laura Plantation mis-memorializes an abhorrent set of power relations. Our guide made some attempt to acknowledge the plight of the enslaved people who had lived there, but true recognition of the subjugation of the enslaved, and appropriate memorialization, were entirely absent. Besides a few anonymous inscriptions on a cellar wall, the tour concentrated on the ups and downs of the lives of the Duparcs, a French Creole family who, from 1804 onward, profited greatly from the use of forced labor to farm and process sugarcane. The costume-drama narrative presented to us was hard to stomach, just as one would find it hard to empathize with the domestic day-to-day of Adolf Eichmann’s family. Such comparison is not made flippantly. Though there are important differences, in their disregard for life, use of forced labor, and dehumanization and abuse of various peoples, Nazism and slavery share an abhorrent moral myopia. 5The copper cauldrons scattered across the site, used for boiling cane during periods of unrelenting harvest labor, provided one of the few signs that this was not some kind of southern Downton Abbey but a site of industrialized cruelty of the highest order.

We left the plantation via an inexplicable gift shop, an entirely misjudged entity. Temporalities had well and truly clashed: from the recollections of the Diagles, back into the Mesozoic era, and forward again to a present in which a scented candle is, for some visitors at least, a suitable memento from a former site of centuries of brutalization and enslavement. An overwhelming cascade of impressions had been accreted in a short time.

Bruce, a descendant of a family who had been imprisoned in such a place, used the journey back to New Orleans to better inform us about the cruel realities of plantation life. He mentioned his forthcoming museum exhibition, which would present the shackles, neck rings, and bells people had been forced to wear and also recount the acts of resistance that are largely absent from places such as the Laura Plantation.6Bruce also explained how the sharecropping system lay within his own memory; his parents directly experienced this iniquitous system of continued human exploitation that persisted long after slavery had supposedly been abolished. The present is no time for complacency: the landscape we moved through made it all too clear refineries – and the deadly externalities their operation involved – were the latest architectural expression of disregard for those whose bodies we consider expendable in pursuing our collective appetites.

Snarled up in traffic, and with a great deal to digest, we slowly made our way back along the River Road in darkness. Amy, possessing a fine singing voice, raised our spirits and encouraged us to join her in a healing round of song.

Driving home in the dark along the River Road, the refineries of the Lower River on the horizon. Photo by Sarrah Danziger

Day two. Back in the bus. This time our destination was the productive heart of the region’s hydrocarbon industry: Baton Rouge. We were headed there thanks to the initiative of Catherine Russell, a sedimentologist who carries out research upriver from the city. Pulling cores of muddy sediment from the land, she tries to better understand the complex reciprocities that have taken place between the river, its sediment, and the geomorphology through which it flows. Once more heading out along the River Road, we arrived at the Louisiana State University (LSU) Center for River Studies, where professor Clinton Willson welcomed us into an information-packed visitor center. We were there to see what is perhaps the world’s largest working analog model of a river system. At ten thousand square feet, the table top model fills a space the size of a sports hall. Varying sediment loads can be simulated across its vast planar surface, which represents the Lower River, approximating the alteration to depositional processes caused by upriver hydroengineering. Like a giant battlefield diorama, the model is intended to allow for strategizing how to best manage the coastal subsidence. As we entered, research-student Godzillas scrambled off the model. A bombastic animated presentation was then projected onto the planar surface of the model, with a disembodied voice telling of inevitable land loss and controlled retreat, a narrative of control projected by the LSU River Studies Center on behalf of the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA).

The presentation inadvertently made it clear that the model is as much a public relations tool as a scientific apparatus. It is used to demonstrate the CPRA’s commitment to the scientific management of Louisiana’s ongoing land loss due to shifting sedimentation patterns, sea-level rise, and land use. What lies beyond the artifice of the model’s closed world are critical voices of those who see the CPRA as a malign force. Its $50 billion comprehensive Coastal Master Plan—published in 2017 and outlining the protection of this section of the Gulf Coast via restructuring, restoration, and resettlement—is considered by some to be insensitive to the lives and livelihoods of those who make their home in the area. With us that day was anthropologist Nathan Jessee, who works with the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe (IDJC). The tribe’s land, Isle de Jean Charles, is scheduled for retreat under the CPRA’s plan.

Earlier, while we viewed information panels on the plan, Nathan had reminded us that such decisions represent the latest chapter in a long history of disappropriation and forced migration faced by these people, who had also been left out of the CPRA’s planning process.7 Given that the largest tranche of funding for the CPRA plan comes from BP, as recompense for the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, and that another oil major had reputedly paid for the $15 LSU million model, critical voices argued that this mediatic apparatus offers nothing more than a distraction. Among the biggest criticisms is that the CPRA plan fails to act on the ongoing role of the petrochemical industry in accelerating land loss. Shifting patterns of deposition, upriver engineering, and the gradient of the tectonic plate that the coast lies on means subsidence is inevitable, but the incessant pumping of oil and gas from coastal reservoirs, the dredging of sediment, and the growing network of subterranean pipelines and their attendant maintenance canals speeds up this loss.8

The river model, and Nathan’s interjection, emphasized that even when one is looking back to the 400-million-year history of the river’s sedimentary processes, there is no aspect of science that lies beyond politics—just as there is no form of politics free from the constraints of the physical world. The model, as such, reflects a wider problem. Like many forms of knowledge, basic scientific understanding about sedimentation, hydrogeomorphology, and Earth sciences in general—and, in all likelihood, a vast amount of the research on which the notion of the Anthropocene is founded—indirectly owes much of its existence to the petrochemical industry.9 Without the deep pockets of oil companies, many geological sites would go uninterrogated and many advances in our understanding of Earth’s shifting composition would not have been achieved. This does not mean we should exonerate a petrochemical industry that has long acted in full awareness of its destructive capacities. But it does require us to recognize that geologists are at the sharp end of the Faustian pact with the hydrocarbon industry that a great proportion of us have entered into.

Dr. Catherine Russell presents to the Clashing Temporalities. “My topics was was in river sediment,” recalls Catherine, “so it was mostly focused on the logic of the layers and the scientific reasoning of the natural environment, but I quickly learned that there was far more to this landscape and environment than these backgrounds.” Photograph by Sarrah Danziger

After more boxed po’boys, Catherine taught us about the science of sediment analysis in a classroom adjacent to the river system model. As she walked us through a slide set, her enthusiasm for the complex depositional processes of the river was clear. She told us about her work on the False River point bar, a formation created when the main branch of the river carved a shorter path through the landscape after a flood in 1722. This horseshoe-shaped body of water appears like a river from certain angles, hence its name, and its structure helps maintain a record of Pleistocene sediment.

Core Sample B3-4 12-16. Photo by Sarrah Danziger Examining a core, LSU Center for River Studies. Photo by Sarrah Danziger

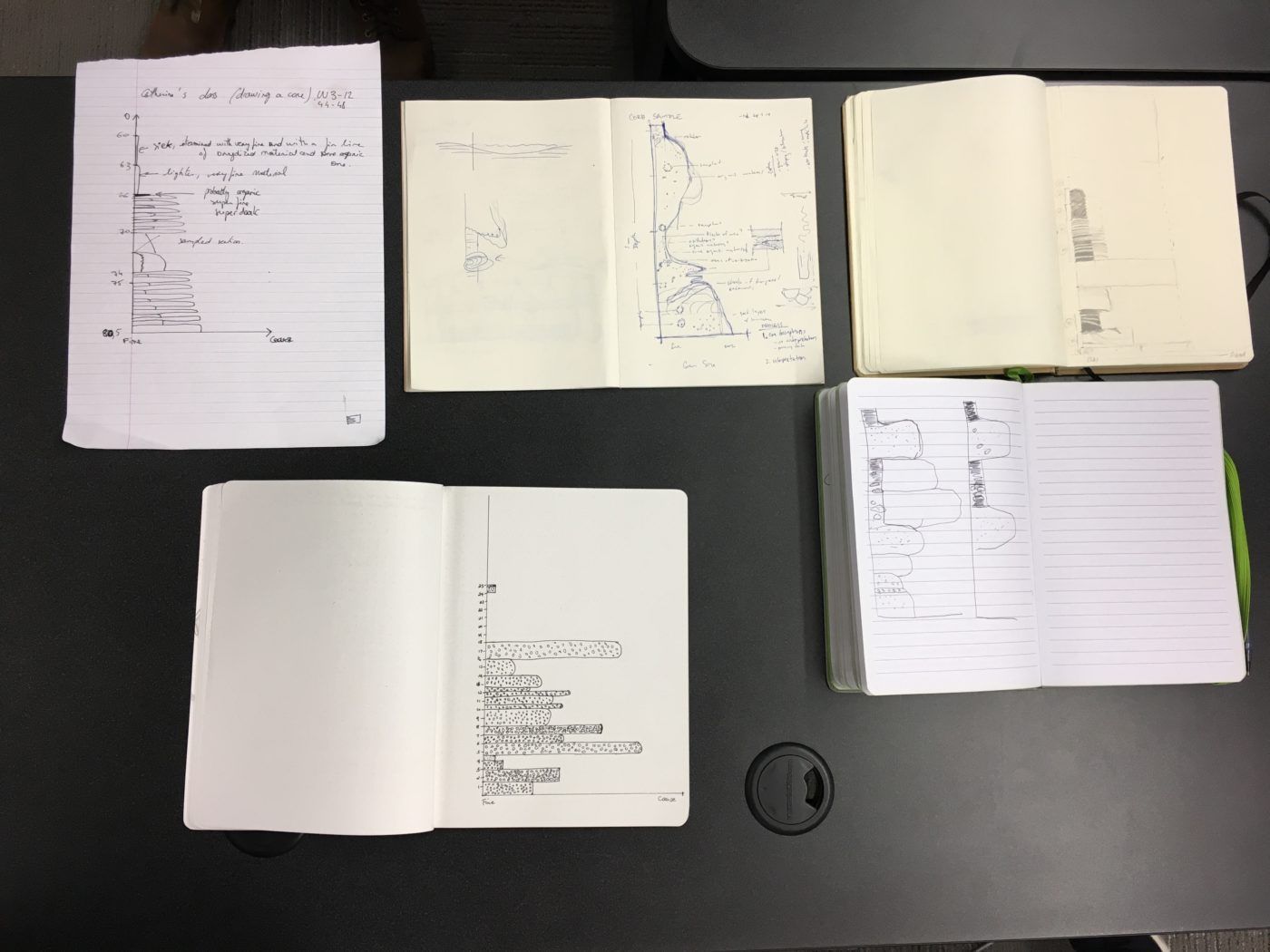

Catherine had arranged for a number of cores taken from near this section of the river to be delivered. We unpacked them from their plastic film, and in doing so began to experience the haptic, material practices of geological work. With her help, we learned how to identify the laminations of a core. We carried out the curiously subjective—and certainly artistic—ways geologists categorize the properties of a core, visually grading the color, appearance, and grain size of its layers.

As part of their work, geologists produce hand-drawn sketches that accentuate the visual appearance of the core to aid characterization. We tried our hand at this task, and the exercise seemed to humanize—or at least it did so for me—a science that may otherwise appear remote, especially for those critical of the totalizing notion of the Anthropocene and the culpability of Earth sciences.

Core Diagrams sketched by various seminar participants. Photo by Neli Wagner Core diagram sketched from Mississippi Sediment Core. Drawing by Seung Hee Cho

Back on the bus, we headed for the False River point bar. With Catherine on the microphone, this increasingly familiar landscape was once more imbued with a strange dynamism as she described the meandering river and its changing structure over time. The Mississippi River Basin is a landscape whose shifting composition can be well understood by glancing at the iconic Fisk maps.10 The work of Army Corps of Engineers’ cartographer Harold Fisk in the 1940s, the maps show the shifting sinuosity of the river over thousands of years. We disembarked from the bus on the western side of the False River Lake and crossed a busy road in a cold wind. From this spot, we could view the lake and gain some sense as to why such seemingly prosaic sites are so important for historians of earthly processes. It takes some imagination to reconstruct the deep history of such a subtly remarkable place. To a considerable degree, geology is a feat of the imagination, using points of evidence from sites like the one before us to reconstruct a deep understanding of the processes that fashioned our terrestrial home. By now, tiredness hung over the group as a result of the steady influx of encounters: we had experienced the imagination and creativity that lies behind geoscientific rigor, while geoscientists had experienced the rigor, critical voices, and breadth of knowledge that underlies many forms of humanistic expression. Points of coherence in world views had been arrived at. Navigating the Old River Road one more time, and singing once more, we returned to Tulane University, where our multi-temporal journey had begun.

With grateful thanks my fellow seminar convenors, Amy Lesen, Bruce Sunpie Barnes, and Catherine Russell, and Scott Wing. Thanks also to Ellie Irons, who reported on the plenary and shared her notes and observations from the day. The seminar convenors would also like to thank the Diagle family for hosting us, and all those who prepared a fascinating range of short essays in advance of the seminar.