Comics and Graphic Novels

Hugo Ricardo Noronha de Almeida and Anna Åberg discuss the realities and politics of “slow media,” using comics as a case study to explore how ideals of “slowness” interface with class privilege, consumerism, forms of attention, and counter-culture.

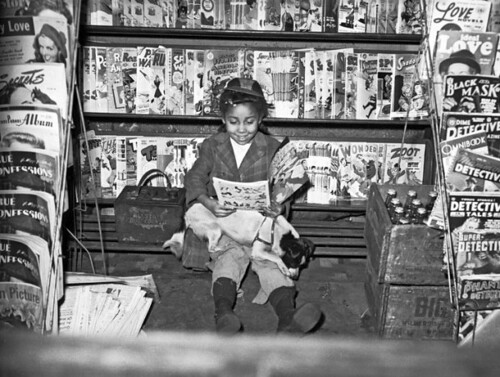

Girl Reading Comics, 1930s Image by Michael Vance, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

This reflection addresses the concept of “Slow Media,” and is an attempt to understand its consequences mostly through the lens of comics and the culture of comics. Slow Media has been characterized as a commitment to “disconnect” and to reclaim our own time from the relentless intrusion of media on our lives—in particular, corporate and social media that vie to commoditize human experience. It has been seen as an inevitable response to the technological revolution that is underway, epitomized by the ubiquitous presence of the Internet in everyday life.1 At a first glance, it is about renegotiating our relationship with the constant stream of information, wherever this negotiation is possible.

In the following discussion, we will suggest our own working definition based on the debate during the Anthropocene Campus 2014 and on previous definitions (in particular the one proposed by “The Slow Media Manifesto”),2 using comics as a lens. As we will see, talking about Slow Media forces us to consider not only media as a means for creative or rhetorical expression, but also how the characteristics of media have social and ideological implications.

Is fast always less? (Is digital always fast?)

It should be clarified that we cannot categorically state kinds or properties of media that are “slow” or “not-slow.” When we speak of Slow Media, we refer to a form of engagement with media. We must also dispel the notion that “connectedness,” accessibility, and specific channels of distribution, mainly the digital, are ethically opposite to Slow Media (Slow Media is not a refusal of technology). Firstly, digital media is a powerful means of personal and public communication and offers a wealth of alternatives to mass media and cultural hegemony. Digital media levels social and cultural inequalities, through such devices as file sharing, social media and hacktivism.3 Its networked structure is refractory to the kind of state or corporate control we observe in unidirectional channels of communication, such as television or newspapers. Our online experience can be fitted to our specific needs, interests, and habits as well as provide spaces for participation and cooperation.

Secondly, the effects of computers and digital media on our cognitive and even physical abilities can both be dramatic and nuanced, and cannot be shoehorned as unequivocally “good” or “bad.” It is true that “being connected” may promote specific behaviors, such as compulsive consumption of social media. It is also an endless source of distractions that demand attention, from email to instant messaging and even game applications.4 At the same time, this accelerated accretion of content has promoted the development of a highly engaged and self-aware Internet culture, which is generating something new from the particular digital environment that it inhabits and the ever-more atomized particles of culture. Collage, pastiche, and derivation have never been so popular in the service of creative exploration. Even though this trend does not restrict itself to the vocabulary of popular culture, the majority of these works range from alternate universe stories with the characters in Game of Thrones, to improbable Star Wars‒Sesame Street crossovers. A particularly impressive example of this phenomenon is the monumental collective comics project Bartkira, which repopulates Katsuhiro Otomo’s dystopic manga Akira with characters and settings from the Simpsons. Even though these works mostly appropriate franchise characters, they do so often by subverting social norms and the ideologies implicit in the original works.5 That these “bastard” creative practices find their place mostly on social networks (tumblr is a good example) suggests that they may be inspired by the very structure of social media—specifically, the constant stream of unrelated information. The juxtaposition of unrelated material may generate accidental meanings and ideas that would not be evident otherwise.

The participatory side of social media can be seen as a plethora of new opportunities to connect, create, and influence the world around you, whether as a fanart creator, in a political discussion, or in an online call for support of a cause. It can also be seen as (and sometimes simply is) a forced obligation, as media becomes more entangled in our public, community, political, and economic lives.

This brief look into digital media suggests that what may be often overlooked regarding Slow Media is that different forms of engagement have different upsides and downsides. The constant, fast bombardment of information through blogs and social networks can also lead to discovery and invention through their own means.

"Information Overload" Image by James Marvin Phelps, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The value of “slow”: work and privilege

However, this issue does not address one of the most important aspects of the Slow Media rhetoric: that disconnecting has become a political act. As our lives become more steeped in media technologies, the freedom to opt out may disappear, which can lead to a democratic problem in itself. Corporate discourse and the productivism that have seeped into our social and personal lives place an enormous pressure on us to remain connected. In many circumstances, such as in academia, we are already expected to work anywhere, all the time. Connectedness has been used to erase the boundaries between work and everything else. By participating in this process, we are complicit with a background level of exploitation that is the motor of the social media industry (not to mention corporate and state surveillance). Our (digital) social relations are effectively commercialized. Thus, Slow Media is not just about reclaiming time from distractions and the alluring light of the screen. At face value, it seems to include an ethics of resistance to the dominant corporate ideology. However, this conclusion can be further problematized.

Firstly, slowness can also provide a framework that goes beyond categorizations based on cultural background, taste, and class, such as high and lowbrow, or classifications such as mainstream and counterculture, which have been compromised by the dissolution of mass culture into increasingly fragmented subcultures, and capitalism’s assimilation of its own critique.6 By placing an emphasis on our relationship with media, rather than the form or content of media, Slow Media further underlines the inadequacy of these categories in contemporary discourse.

Secondly, slow movements have been criticized on the basis of their relation to concepts such as class, taste and privilege, and the slow media movement needs to be examined in this regard. Heather Mendick has pointed out that “Slow is both classed and gendered, re/producing a particular relationship to self, which requires not just stability of employment but an individualist way of being, constituting selves that calculate and invest on themselves for the future.”7 As an example, within academia “slow” does not necessarily mean “work less,” instead it means “work more with what is important”: research, in other words, as opposed to administrative tasks and mailing, etc. On the other hand, the possibility of giving up these tasks rests on the obligation for someone else to do them. This other person most likely does not have the choice to opt out of the task. Similar discussions have been lifted within the slow food movement, the slow travel movement and the slow fashion movement, pointing to the fact that money and the time to hunt down specific types of food, travel, and fashion are not necessarily available to everyone. A slow movement is thus not necessarily a justice movement and, as has been pointed out, the “good food” movement would stand to collaborate more with the “good jobs” movement.8

Further, the idea of slow as a concept that we use to valorize our time and build identity is steeped in a middle-class rhetoric. Most of the time, those who are working less today not through choice, but compulsion, are completely absent from the discourse. The slow pace of those people, who do not have the privilege to be able to slow down, instead tends to be seen as laziness. Thus, the kind of slowness being valued depends on the social context of the actor.

As pointed out by author Tracie McMillan regarding slow food: “When the food movement poses home cooking as a moral choice, it is making a pretty alienating, class-based argument. […] We have to value work in the home. But we also have to be realistic about how you can feed your family if you’re not a highly-skilled cook and you’re already working 40 to 50 hours a week at seven dollars an hour.”9

The concept of slow media may not embody these problems in the same way as the other slow movements, but the underlying ideology is similar, and this calls for afterthought. How can we democratize media participation, and at the same time ensure that opting out is a possible choice? And perhaps most importantly, what is it that slow media wants to change? Is it individual lifestyles, or larger institutional structures? Can Slow Media be more than a buzzword that fetishizes old media for affluent audiences, further participating in compulsive consumerism and aggravating environmental impacts and class-based distinctions?

The discussion until now has offered personal solutions to systemic problems. While Slow Media proponents reject corporate control of the internet, they readily acknowledge the all-encompassing nature of contemporary capitalism.10 In a pragmatic move to address this reality, Slow Media advocates support of the hijacking of marketing tools as an adaptive strategy.11 “Slow” is offered as an umbrella term, a brand promoting an open source economy, leaving anyone who is unable to pay for expensive, non-corporate goods outside the loop of slowness. By presenting a market-based strategy, their offer is reduced to aspirational fantasies. Slowness becomes another resource for advertising, as exemplified in this ad for condoms, which argues in favor of disconnecting, because digital media is distracting you from a “healthy sexual life” (and from buying condoms).

These developments are expected, but they may not be the only possible outcome of a slow ethics. In the following discussion, we will address the issues of class, participation and sustainability in comics and their surrounding culture.

The cultural value of comics

Due to their ambiguous cultural value, comics are a good device to articulate ideas surrounding class, taste, and ideology, as well as providing a specific social setting in which to “observe” how Slow Media can serve as a form of resistance to dominant values and practices. It is their complicated social standing that makes them a compelling model to analyze the arguments for a “Slow Media,” and not any sort of structural or formal vantage over other arts or forms of communication.

Comics are not satisfactorily described by any traditional dichotomies of cultural value or ideological allegiance. Historically, they are an art form conceived for mass reproduction, which has traditionally existed outside the power structures of the High Arts. Even among comics academics and artists, the social status of comics is unresolved, as some argue towards the (long-deferred) institutional and cultural legitimization of the art form, while others believe that comics best serve themselves and the larger cultural milieu by keeping a marginalized status—unsupervised and at odds with the tastes of the dominant culture and a certain notion of “respectability” that the latter usually provides.12 To some, this specific regime allowed comics to experiment and develop autonomously, in a “safe zone for play” where “nobody is looking.”13 This cultural isolation has led to the development of countercultural movements such as the underground comix scene in the United States, but it has also allowed the “speciation” of highly codified genres such as the superhero in the United States, or shoujo manga in Japan. In this view, acceptance into the “pantheon of the Arts” could compromise the uniqueness of comics’ culture. At the same time, it can be argued that the historical isolation of comics has sometimes led to a myopic understanding of the medium, both inside and outside of comics’ culture.

For Éric Maigret, who analyzes the francophone-comics world, this debate exists in terms of a negotiation between two opposing forces: “cultural legitimacy” and all forms of resistance to it—in particular countercultural movements and the acknowledgment of multiculturalism.14 Cultural legitimacy comprises a set of commonly accepted rules meant to distinguish institutionalized art forms from other cultural practices. They are usually imposed by institutions, policy makers, and cultural commentators.15 Cultural legitimacy reinforces hierarchies of form, theme, and convention that are meant to protect cultural hegemony and perpetuate class privileges. For comics, it is mostly their “hybrid” nature that is problematic: by “subjugating” text to image, comics symbolically reverse the supposed superiority of the written word over the “immediacy” of the image.16 The scandal is both semiotic and social, as the written word constitutes the nobler mode of communication of the educated, and the presumed accessibility of images empower the illiterate working classes.17

A set of assumptions further hamper the acceptance of comics as a legitimate art form, specifically the “essentialization” of their features and audiences (comics are mass produced picture stories intended for children, the immature, and the illiterate). For all of these, Maigret argues that it is useless to work towards the legitimization of comics (or other marginal forms), because the criteria for legitimization exclude comics in principle.

Nowadays, the dominant discourse commonly addresses the arbitrariness of hierarchies in the arts.18 Maigret calls this environment a “post-legitimate” culture, where references to legitimacy are increasingly inadequate. He suggests that comics should look instead for “recognition” of their own attributes and merits, placing an emphasis on individual achievements and not on the virtues of an entire medium. This “post-legitimate” environment has also seen a general opening up of comics to the discourse and formalities of the fine arts, as in the works of authors such as Gary Panter, Yuichi Yokoyama, and CF. This movement is not unidirectional, but radiating, frequently involving a mix of references and aesthetic vocabulary from low- and highbrow sources, further undermining any attempts at categorization. Thus, it seems that when everything is fair game, comics are encouraged to expand in form and content, in an increasing dialogue with other arts.

But whether comics are or should be an institutionalized art form, is just part of the crisis of identity of comics in traditional paradigms. For example, American mainstream comics, which are mostly populated by superheroes, do not benefit from the cultural capital that its designation implies. Superhero comics were effectively mainstream in their early days, when they were sold in newsstands throughout the United States, with monthly circulations in the millions.19 Nowadays, they are sold in specialty stores, and mostly appeal to a niche audience that is well versed in the conventions of the genre and the backstories of its characters and universes.20 They are the “mainstream” of comic book culture not because they have conquered a mainstream audience, but because they form an established industry that represents the largest share of the comic book market in the United States. In fact, superheroes are just the visible face of a subculture that values specific forms and genres in detriment of the dominant forms in the larger culture.21

"Big Planet Comics" Image by ZimriDiaz, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The different faces of the comic profession and participation

However, even though superhero comics resist dominant cultural norms in respect of form and aesthetics, the genre still largely subscribes to dominant social values, including narrative, political, cultural, racial, and sexual biases (exceptions notwithstanding). In addition, they are produced through an assembly-line-like process that involves several writers and artists. These creators are hired to continuously develop characters and series in never-ending narratives within a shared universe, all of it owned by the publishing house. The extremely intertwined nature of these narratives produces captivating results in fictional world-building, while compelling the reader to buy as many titles as possible, in order to comprehend all the ramifications of these stories.

So, even though they are a niche product for an extremely engaged audience, the making of superhero comics approximates industrial standards of production, accompanied by narrative strategies that promote compulsory consumerism. Generally speaking, it is an industry that rewards the ability to work fast and produce derivative and easily recognizable material. This is not to say that all superhero comics are highly derivative, or that derivation per se is inherently bad. Even though they comprise an industry in which their creative process resembles an assembly-line-like process, the fact is that these works are still performed through a complex collaborative artistic process, similar to that the slow media proponents advocate. In fact, this industrial process is still able to harbor countless celebrated works for their technical and artistic achievement.

From a material point of view, comics-making is very time-consuming, and is generally a solitary occupation (some artists work in shared studios). But they are also very cheap compared to other visual narrative media such as film or animation. They require only one person to create the whole work (working as writer, artist, letterer, editor, etc.), and achievements or shortcomings are the author’s responsibility. It is a very accessible visual narrative media in terms of production, even if it requires extensive training and practice (many comics artists are self-taught), and even if its vocabulary (i.e. the conventions of comics such as word balloons) isn’t as universal as it is usually proposed to be. It is also a very powerful means to construct whole fictional universes without resorting to expensive means, collaborators, and technology.

Thus, the cultural status of comics depends on who we ask. They can be simultaneously high- and lowbrow, industrial and authorial, mainstream and countercultural. Pinpointing comics as a whole along these axes will only reinforce the obsolescence of their criteria. Their slowness also allows us to make significant (and often conflicting) observations on their actual and potential value as a general creative and communication process.

Collectability and compulsory consumerism

As Charles Hatfield states, both the “mainstream” and the “alternative” comics embody a “curious mix of values, a blend of countercultural iconoclasm, rapacious consumerism, and learned connoisseurship,” on the one hand appreciating their outsider status, and on the other vying for wider public and institutional recognition.22

Cyclically, superhero publishers resort to strategies of increasing sales by appealing to the collectible value of their comics or by interconnecting stories to coerce their readers into buying many more titles. For these reasons, the commercial aspects of “mainstream” comics do not reflect a Slow Media ethics of production, being mostly an industrial product following genre and editorial guidelines, which are designed for a specific audience. On the other hand, the current independent comics scene is made up of either authors who actively react against the corporatist ethics and models of “mainstream” comics, or, increasingly, authors who come from “outside” the field and approach the media from a fine arts perspective. Overall, these are authors that use comics as a cheap mode of expression, to produce works with highbrow intentions. Even though they distance themselves from the formulas of mass culture, and generally favor a critical perspective on comics and the broader society, they can still be regarded as favoring consumerism, offering alternative consumptions, rather than an alternative to consumer culture.

In fact, the lines blur at comic book stores, where we can find mainstream, independent, and even self-published comics (naturally, with varying degrees of prominence). At the same time, comic book stores are places of social engagement, where customers go to buy but also to discuss comics in their various manifestations. In this regard, comics in general are not necessarily aligned with a culture of careful management of resources, even though an attention to the object can promote a deeper engagement with the floppy magazine, or the book, and their mechanical and material properties. Nevertheless, a culture of resistance to dominant values based on commercial success still exists, in particular in the more restricted circles of self-publishing and comics zines.

Future reflections: What can slow be?

What do we show in our discussion about comics as slow media? In a sense we are using comics as a way to discuss what slow media can mean. We have gone through things such as cultural contexts, economical and production contexts, contexts of participation, and of material sustainability.

“Slow” is not as easy to define as one might think. “Slow” can work on different levels, individual and structural, and these levels may or may not be compatible. We need to make sure that “slow” is a possibility/option. Otherwise we run the risk of allowing Slow Media to be immediately co-opted by market interests, through adding value to consumer products via the fetishization of old media.

What is a systemic Slow Media? Can we look into niche cultures such as zine culture for strategies for a systemic change?