Born a Minim

A "scaffold" structure, self-assembled by Eciton burchellii army ants across an inclined surface. From experiments in "Individual error correction drives responsive self-assembly of army ant scaffolds," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(17)., M.J Lutz, C.R. Reid, C.J. Lustri, A.B. Kao, S. Garnier, & I.D Couzin, 2021. Photograph by Matthew J. Lutz

Ecit/on-boarding: Welcome to the Colony! ?

If you’re reading this, you’ve finally eclosed from the pupal stage, and are probably wondering about the next steps on your journey as a new Eciton burchellii worker. Let me be the first to say: We’re excited to have you on board!

It may feel like you’re stumbling about blindly at this point, but don’t worry—this is perfectly normal! TBH, we’re all a bit in the dark here, as our simple eyes are only capable of basic light sensitivity.

Your brain has been completely remodeled while in your pupal cocoon, and you’re still what we call a “callow” adult, meaning your cuticle has not yet hardened completely. So just hang around the bivouac until you get your bearings, pick up the colony vibe (and the scent of our pheromones), and focus on learning from this doc!

Once you’re up to speed, you’ll be ready to join our marauding swarm in no time. In the meantime, don’t hesitate to ping your nestmates with any questions. We’ve all been where you are (#startedfromthebottom), and your sister workers will be happy to help—after all, we’re one big non-hierarchical family here!

For reference, this onboarding doc is organized as follows:

Ecit/on-boarding: Welcome to the Colony! ?

Frequent army ant questions (FAAQs) ?

Swarm life: Move fast and raid things ?

Our HQ: Barro Colorado Island, Panama ⛰

Self-assembly tutorial: Bridges, etc. ?

Performance Reports: Pupal & Larval Stages ?

References

Frequent army ant questions (FAAQs) ?

Before we dive in too deep, let’s address a few burning questions you might already be wondering about (with more to follow below):

“I was born a minim. Will I ever be able to change size or take on other caste roles or opportunities?”

- The short answer is, no. Your caste was determined by the needs of the colony at the time, and your unique size is a result of how much you were fed as a young larva. But don’t worry! Every caste is important, and everyone has their own special talents to contribute to the colony. Even as a minim (or “minor”) worker, you will play a major role! In addition to brood care—one of your main duties—you’ll also take part in raids, and you’ll often end up as a crucial component of the bridges and other structures we build (including the bivoauc, our temporary nest).

“What’s up with the queen? Will I ever get a chance to meet her?”

- We know you’re excited about that, and we’re happy to report that yes, this is a distinct possibility. 🙂 If you’re lucky, you might even get to swarm around as part of her retinue during one of our nightly emigrations!

“I’m nervous about my first raid. Is there anything else I can do to prepare?”

- We’ll give some more tips below, but when in doubt, just go with your gut! Once you’re part of the organized chaos of a raid, you’ll feel like a natural when your senses and instincts kick in, finely tuned over millions of years of evolution.

“What if we come across another colony while raiding?”

- We share this island with other army ant colonies, and it’s inevitable we sometimes cross paths. As competitors, we may not be the best of friends, but we maintain a healthy respect for each other, allowing safe passage. Avoiding needless conflict over territories or colony egos lets us all avoid losses and get on with our business.1 NB: Just be careful not to get mixed up with the wrong colony! Each colony has a unique odor for a reason, and this can have harsh consequences. 🙁

“What about other species? Are there any we get along with?”

- Definitely! In fact, it’s been shown that over 300 species actually depend on us. That’s what we call giving back to the community. 😉 These include many species of antbirds2 that follow our raids, along with butterflies and flies. More intimately, some of these are called inquilines, which you’ll get to know up close, as they live within our colonies and come along on our raids—including over 40 species of mites, and at least 30 beetle and fly species.3

“Where are the males? How does reproduction work here?”

- Like yourself, all the workers in our colony are non-reproductive females. Occasionally the queen will produce a batch of males, who fly off and mate with queens of other colonies, and eventually, our colony will reproduce by fission, when some of us split off with a new queen. This process makes us immortal (in theory) at the colony level, which we think is pretty cool! But this will all be covered in a future advanced training doc, so don’t worry too much about these details for now. 🙂

“Why do we need to move so often? Isn’t this a waste of energy and time?”

- While the nomadic life can be a pain (especially for those who dream of settling down someday), it’s simply the price we pay for being so successful—and we’ll take that trade-off any day!

“What about labor relations? Can we form a union? Isn’t the constant travel stressful? etc…”

- We’re aware that we ask a lot, but our workforce is highly dedicated and satisfied, and our lack of hierarchy makes everyone feel empowered. As a close-knit family, we believe structures like unions tend to create artificial divisions, so we prefer other forms of conflict resolution. We also offer a number of benefits you won’t find elsewhere, including:

- All the prey you can handle, in larger sizes than you could ever subdue individually, processed by a highly skilled and cooperative team, using advanced collaboration tools.

- Travel to new patches ensuring a constant supply of fresh leads, new opportunities for skill-building, and the excitement of exploration.

- Few predators or competitors to worry about. In fact, we’re considered top predators in the ecosystems we dominate!

- Fast-paced, agile/lean, startup-like environment, as part of a close-knit team dedicated to the greater good (of the colony).

- Constant growth mindset: “If we’re not growing, we’re dying.”

…if these pique your interest, read on for more!

Close-up photograph of a bivouac (temporary nest), here built by the closely related species Eciton hamatum. Photograph by Matthew J. Lutz

Swarm life: Move fast and raid things ?

We’ll start with a basic overview of colony operations. While most ants deploy solitary scouts to search for food independently, we always forage as a group, cooperating to capture and overwhelm prey. This enables us to exploit prey types not accessible to individuals, like large arthropods and the brood of other social insect colonies.

As E. burchellii army ants, we pride ourselves on our dramatic swarm raids. These can stretch for over 100m through the rainforest, and allow us to process tens of thousands of prey items per day.4 With this logistical prowess, we tend to dominate the competition, resulting in our well-earned status as keystone predators.5

Critical to the organization of these raids are the chemical pheromones we deposit in the environment (and respond to) during foraging.

“How do I pick up and follow a trail?”

- To pick up trails laid down by your fellow workers, use your antennae to sense around on the ground as you walk, until you pick up the scent.

“What about laying my own pheromone trail?”

- Depositing your own chemical trail is as simple as periodically dragging your gaster along the substrate.

- Upon encountering a potential source of prey, you should return to the nearest raid column while depositing pheromone, then run in either direction and contact other workers with your antennae.

- Repeating this process initiates a cascade, as others you recruit will perform the same activity, attracting even more workers!

As you can see from the video above, we’re a pretty conspicuous and (we think) charismatic species. ? Raiding above ground, while constantly moving into new territories to find prey resources, it’s difficult to hide much about our operations compared to many other, more cryptic army ant species—some of whom we evolved from.6 But we’ve learned to embrace this high profile, and we’re all about transparency.

In fact, through strategic partnerships with independent (human) researchers, we can proudly say that we’ve become one of the most well-studied ant species on the planet! Sharing our data and allowing these researchers unprecedented access allows us to take advantage of human sensing and recording technology, freeing up resources that we might otherwise need to devote to internal research. This lets us focus on doing what we do best: Move fast and raid things ?

In return, we allow a select few humans7 open-source access to our algorithms (for implementing in their still-primitive distributed control and organizational systems), and we perform some outreach and service, occasionally clearing their residences of arthropods they consider pests.

- For the record, we remain opposed to the continual destruction of our habitats by humans and their ongoing warming of the planet.

Therefore this remains an uneasy alliance, and if a human gets too close, you should never hesitate to defend yourself (or seek help from the nearest soldier)!

It may seem hypocritical for us to judge human aggressiveness, or their obsession with conquering new territories for resources, as we share similar tendencies. However, we like to think of our predatory lifestyle more as a form of “creative destruction”8 since we play an important ecological role in structuring the communities on which we prey,9 and our constant movements ensure we don’t deplete resources locally.

Cargo ship transiting Lake Gatun section of the Panama Canal. Photograph taken from Gamboa, the mainland departure point for boat transport to Barro Colorado Island Photograph by Matthew J. Lutz

Our HQ: Barro Colorado Island, Panama ⛰

Yet, humans do make some good decisions (if not always intentionally). As a case in point, the place we call home, Barro Colorado Island, was created as an unintended consequence of one of the largest human infrastructure projects ever, the Panama Canal.

For some context about the site of our operations, as we strive to optimize the logistics of prey transport on daily raids, we give a TL/DR version of this origin story here. Those interested in learning more should dig into Megan Raby’s Ark and Archive: Making a Place for Long-Term Research on Barro Colorado Island, Panama10 *during break times, of course!

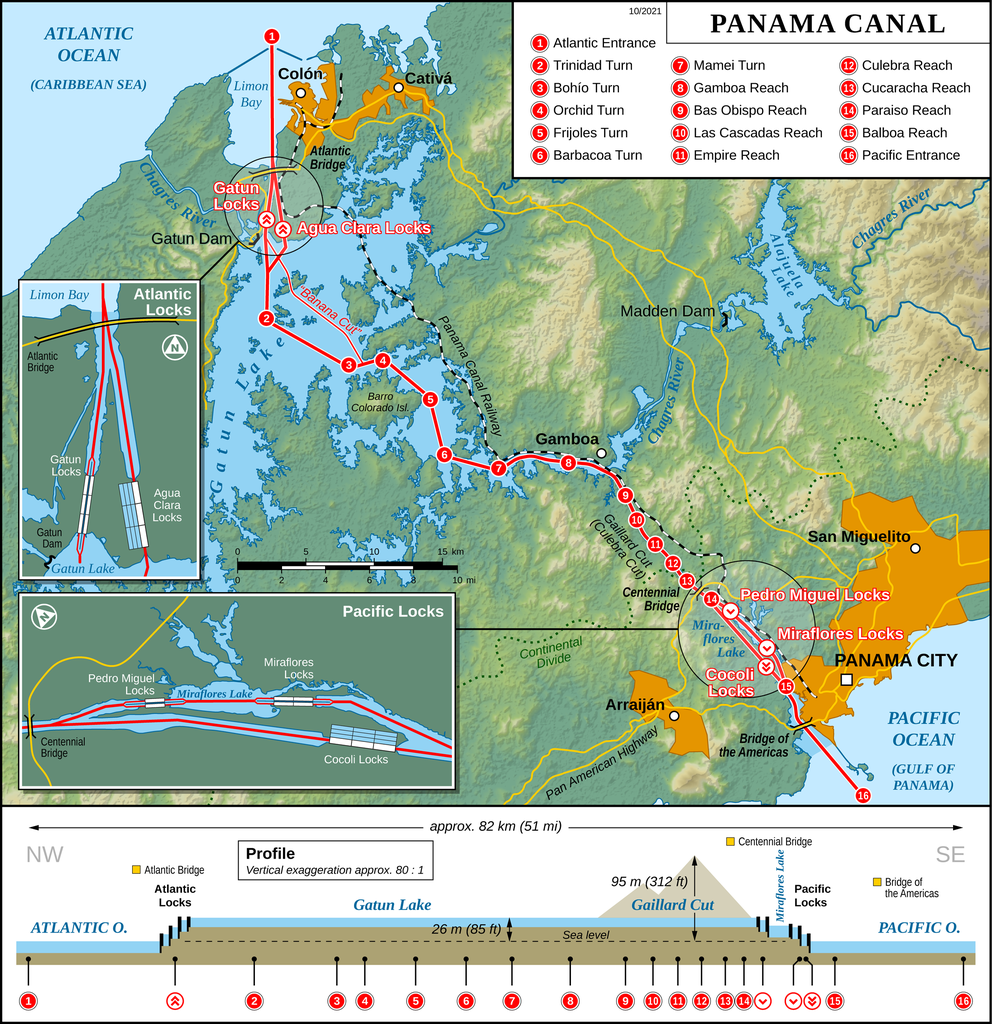

Map of Panama Canal (top) with sectional diagram (bottom). Barro Colorado Island can be seen around red points 3, 4, and 5. Wikimedia Commons, Thomas Römer/OpenStreetMap data

As a crucial step in building the Panama Canal (which took roughly 10 years, from 1904-1914), humans constructed Gatun Dam, the largest in the world at the time. This flooded a massive swath of Panamanian rainforest, resulting in what was then the world’s largest artificial lake, Lake Gatun. As shown in the map and cross-section above, the areas flooded by this lake make up almost half the length of the canal.

Of course, this massive intervention also displaced tens of thousands of human residents (among other species). While the implications for human societies, geopolitics, and the history of colonialism are beyond the scope of this doc, many resources are available for the interested worker.

In particular, we recommend Marixa Lasso’s book, Erased: The Untold Story of the Panama Canal,11 which gives an account from the Panamanian perspective of the disruptive impacts resulting from the colonialist agenda of US interests behind the construction of the canal.

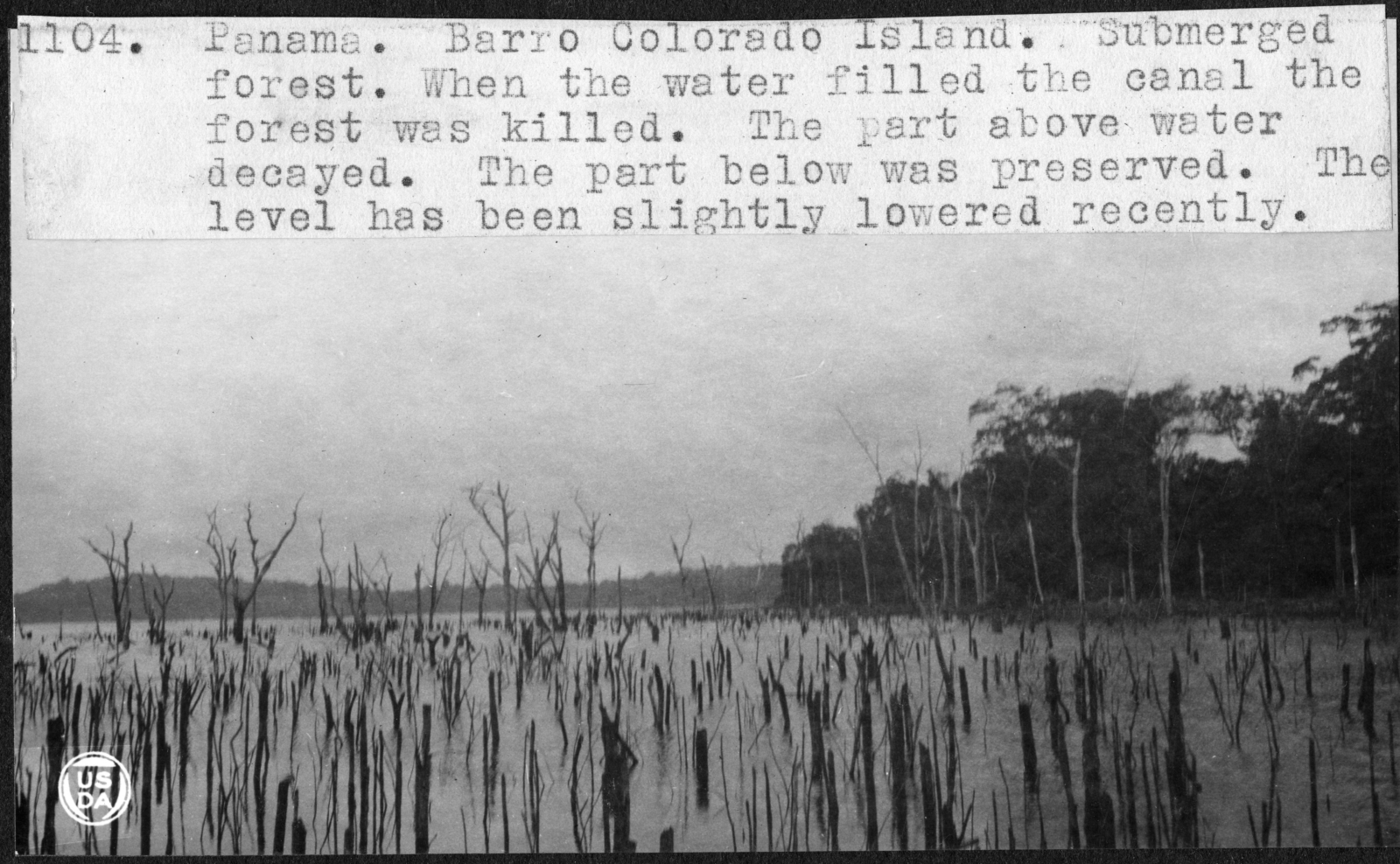

Submerged forest surrounding Barro Colorado Island, 1923. Photograph by Albert Spear Hitchcock, courtesy Smithsonian Institution Archives, image SIA2009-2921

The project submerged 42,500 hectares of the forest-covered Chagres Valley. This forest had been no stranger to human presence: indigenous agriculture went back over two thousand years. Nevertheless, the landscape changes generated by the construction of the Panama Canal are difficult to overstate. For US contemporaries, the canal represented the paramount symbol of the triumph of American civilization over tropical nature. In the canal, roughly halfway between the Caribbean and the Pacific, lay Barro Colorado. This island of “red mud” was at once new and ancient: a by-product of an engineering feat to inaugurate a modern age and, simultaneously, a living monument to the ancient forest sacrificed below the water’s surface.

Excerpt from Megan Raby’s Ark and Archive: Making a Place for Long-Term Research on Barro Colorado Island, Panama.12

However, on the bright side for our colony and the surrounding forest, the flooding that created Lake Gatun also left the top of a former mountain isolated as a new island, eventually named Barro Colorado. Thanks to a few thoughtful humans, this island was designated as a preserve in 1923 and has been protected as a biological research station ever since.

Remaining relatively untouched by human development since its isolation, BCI’s protected status and relative accessibility have made our home the best-studied tropical ecosystem in the world.13 These attributes have also led to its long-running status as a hotspot for human studies of our species.14

Aerial view of BCI, with ship traversing Lake Gatun in the foreground, 1986. Image courtesy Smithsonian Institution Archives, image # 86-10915

Self-assembly tutorial: Bridges, etc. ?

Temporal constraints shape many aspects of our behavior and morphology.15 In response, traffic on our trails is among the most highly organized of all ants, with adaptations that enable us to maintain some of the highest running speeds around. These include the spontaneous formation of self-organized traffic lanes16 and our ability to modify the environment with self-assembled structures.

The bivouac, our temporary nest, is the most complex of these. However, this will be an advanced topic for future training sessions. For now, we want to get you started with some basic building behaviors, including bridges, flanges, and plugs.

Our bridges are highly responsive to the flow of traffic, adjusting their size based on the amount of traffic they need to support. They also break apart quickly if the flow of traffic is stopped, and are quickly restored to their original size if disturbed.17 These structures are integral to our foraging success, and we consider them one of our main competitive advantages!

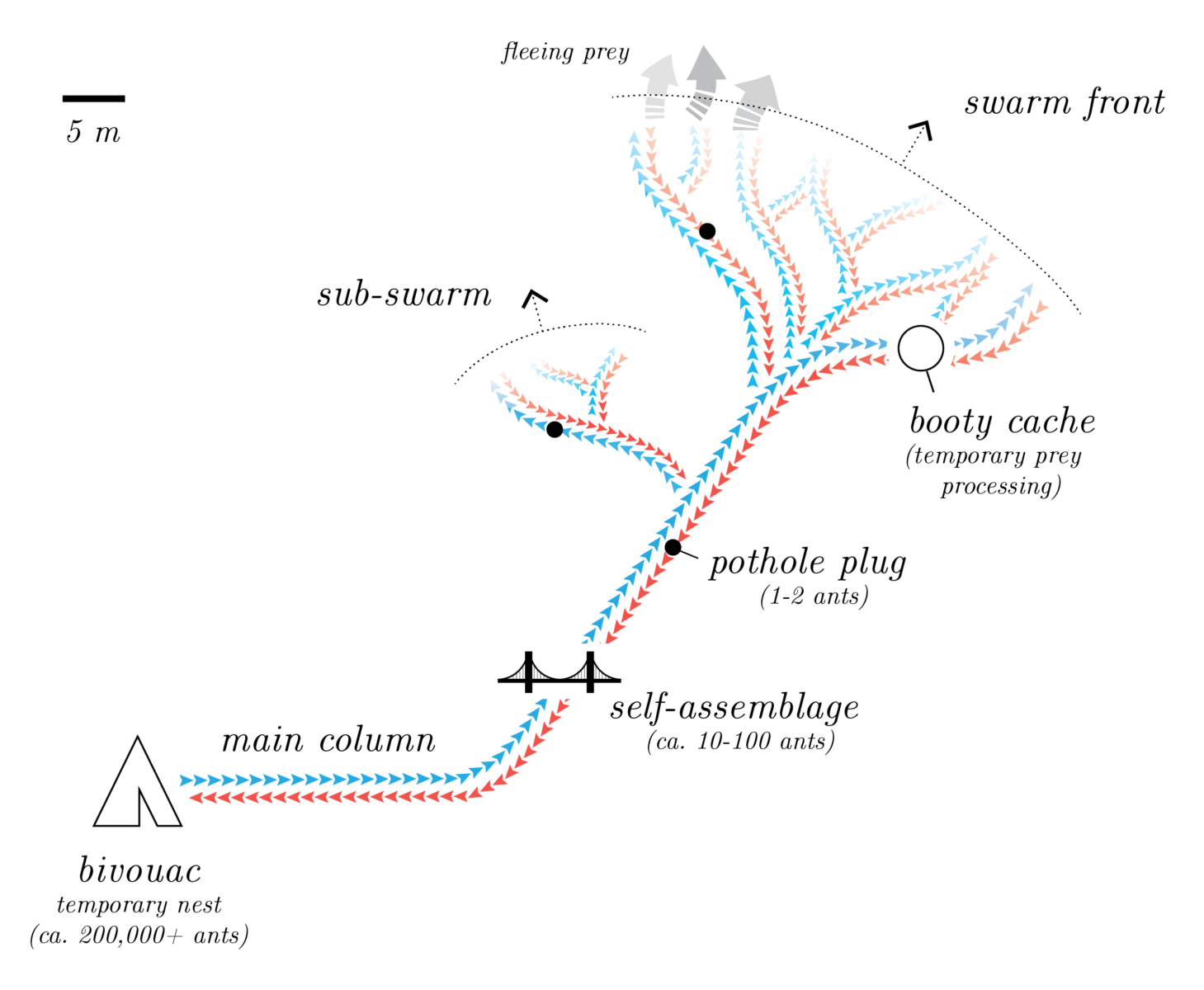

Schematic overview of a typical swarm raid. Leaving the bivouac at dawn, the swarm front advances over the forest floor, flushing out arthropod prey from the leaf litter. Captured prey are dismantled and transported back to the bivouac, along a fan-shaped network of trails merging into one main column. Self-assemblages (bridges, flanges, and scaffold structures) occur periodically throughout the trail network as needed to facilitate traffic flow (diagram shows just one, for clarity). Diagram by Matthew J. Lutz. Adapted from a diagram by D.J. Kronauer published in Army Ants: Nature's Ultimate Social Hunters, Harvard University Press, 2020

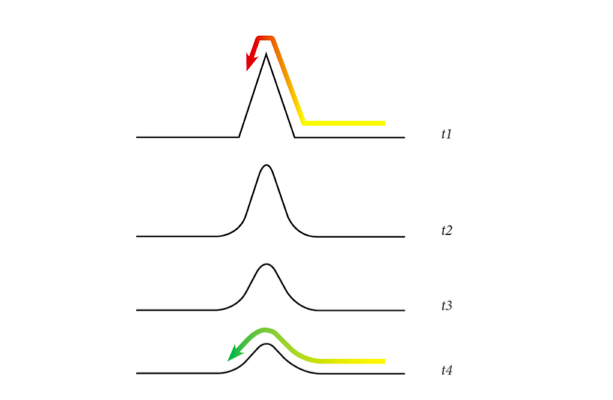

We use bridges to create shortcuts, as shown in the diagram and video below. Our bridges move down to a point at which the cost of locking up additional workers in the structure begins to outweigh the benefit of the shortcut created, which is kind of a collective computation we make together.18

“Who decides how far to move a bridge?”

- Believe it or not, this calculation is something that happens automatically at the group level—so you don’t even need to think about it!

- Rather than any individual controlling the process, our bridges move by the combined action of new ants joining at the bottom of the bridge, while ants already in the structure gradually leave from the top.

Image of bridge movement at an angle of 20 degrees, from experiments in "Army ants dynamically adjust living bridges in response to a cost–benefit trade-off," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, C.R. Reid, M.J. Lutz, S. Powell, A.B. Kao, I.D. Couzin, and S. Garnier, 2015. Diagram by Matthew J. Lutz

To get started, you can initiate or join a bridge whenever there’s a surface or another ant to grab onto. You’ll know when to stay in or leave a structure by sensing the traffic flow.

If no other ants are walking across you, that’s a sign you’re not needed at that point, so you can let go and move along with the flow of traffic.

But if you find yourself supporting a lot of traffic, stay put and hang in there! Get a good grip of the nearest surface or ant with your tarsal hooks, and allow your legs to lock into place. Your colony mates will appreciate your bridge service, and will be sure to do the same for you in the future. 🙂

For your first assignment, team up with members of your cohort and try following your instincts (along with the instructions above) to create some bridges together.

Start small, and remember, practice makes perfect! ?

Performance Reports: Pupal & Larval Stages ?

Finally, as part of a colony of hundreds of thousands, we know it can sometimes feel like you’re just a cog in a machine, but rest assured that your contributions are appreciated! Through both the pupal and larval stages, we’ve watched your growth closely, and the team has been duly impressed with your performance. To motivate you to keep up this great work, here are a few glowing reviews from mature workers who interfaced with you during your cohort’s development (with individual identities withheld):

- “During our nomadic phase, minim2021-003898 showed calm and composure as a larva, trusting her teammates completely, even while transported in their mandibles for hundreds of meters through the forest each night.”

Anonymous worker, Emigration and Transport Team - “The hunger signaling of minim2021-003898 was impeccable, and kept even the most jaded team members motivated to hustle out on the trail in search of new prey leads.”

Anonymous worker, Brood Care Team - “During feeding, minim2021-003898 showed incredible prowess, externally digesting even the toughest bits of arthropod prey!”

Anonymous worker, Brood Care Team

We’ll continue to update this doc with more feedback and new tutorials as you progress along your journey with the colony. In the meantime, feel free to peruse the references below for more info. ?

Until then,

Happy Raiding!

? ? ?