Arriving in the Anthropocene: 300 years of adaptation to hurricanes and Mississippi floods in New Orleans

One focus of environmental historian Eleonora Rohland’s work is the city that hosted the Anthropocene River Campus in November 2019: New Orleans. In keeping with many of the themes underpinning the Campus seminars, here she explains how the question of adaptation so present post-Katrina has a much longer history in NOLA, a city and society with a heightened awareness of just what it means to arrive in the Anthropocene.

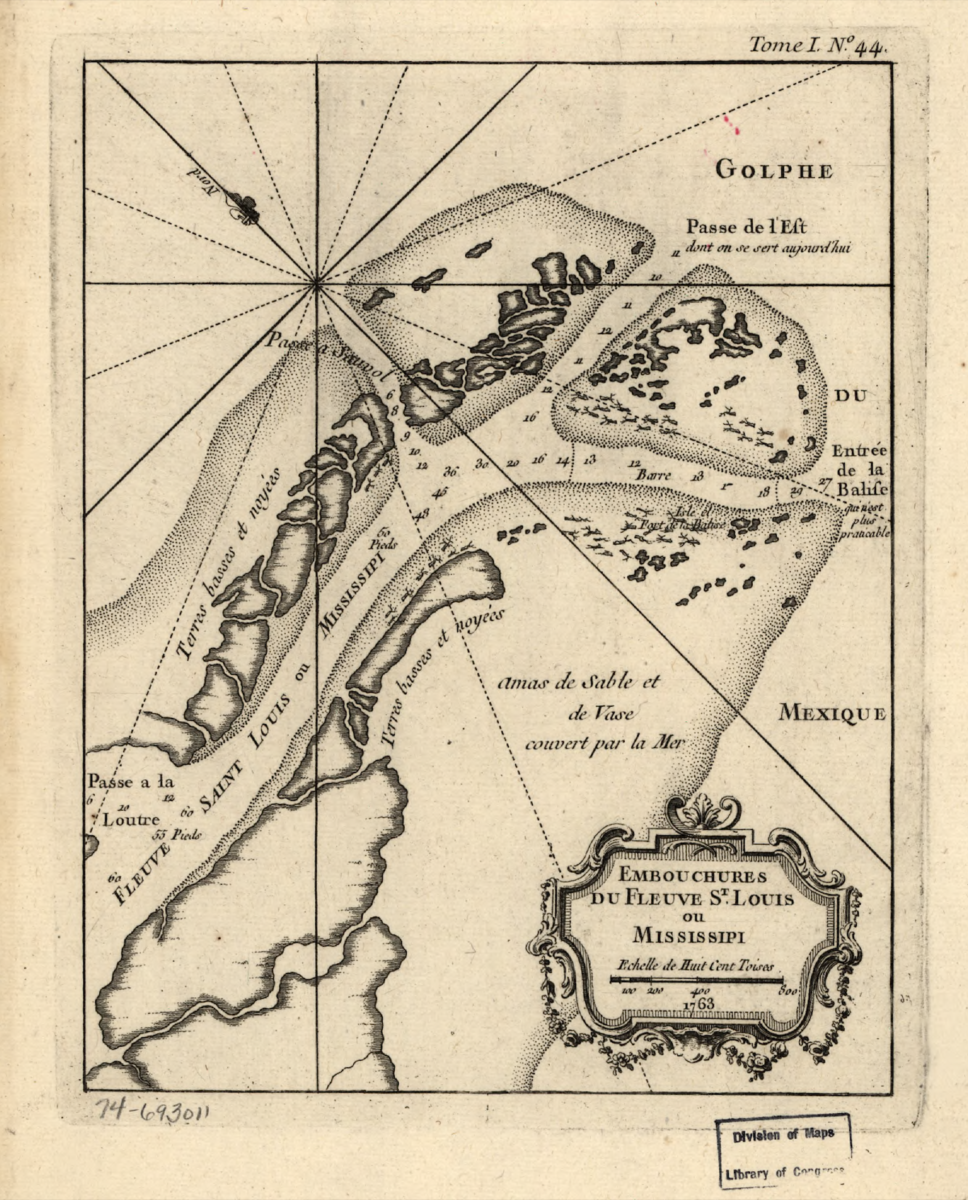

“Embouchures du Fleuve St. Louis ou Mississipi,” map by Jacques Nicolas Bellin, 1763, showing the (natural and human-made) changes in the mouth of the Mississippi since 1744. Reproduced from an original in the collections of the Geography & Map Division, Library of Congress, G4042.M5 1763.B4. Scan: Author’s own.

After Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005, an emotional controversy about whether the city should even be rebuilt briefly created waves in the media but was consequently almost forgotten. Of course New Orleans would be rebuilt! Nevertheless, the question of how to secure the city from future hurricane impacts in an age of climate change-driven rising sea levels and sinking soil has remained subject to ongoing contestation. Richard Campanella, an expert in New Orleans’s historical urban geography has compared the city’s situation to a “geological cancer” that would reduce its eventual lifespan. “We will not be here a thousand years from now. If we do things properly, we might be able to squeeze out a few hundred years.”1

The viability of an urban space that is at risk from natural disasters whose strength and number are likely to increase with climate change is, at its heart, also a question about the adaptive capacity and vulnerability of its society. So, prompted by Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent debate over how to rebuild the city, this research was guided by the following questions: What had been known about hurricanes and the flood risk to the city at the time of its foundation in the French colonial period in 1718? How did the recurring threat shape New Orleans’ diverse society? What was the influence of different political regimes, from the French and Spanish colonial ones to the American, on adaptive practices? And, what can we possibly learn from this history? This research was published as Changes in the Air: Hurricanes in New Orleans, 1718 to the Present in the Rachel Carson Center Series Environment in History: International Perspectives with Berghahn Books earlier this year.

Vulnerability and adaptation to climatic extreme events change historically, and their evolution can only be studied over the long term. Therefore, this research examined cultural and technological adaptation to hurricanes in New Orleans over the almost 300-year timespan of the city’s existence, from its foundation in 1718 to the present. With their levee-building technology, the French carried out far reaching and deeply anthropocenic modifications to the Mississippi delta and the banks of the river from 1719 onwards. This engineering created technological and ecological path dependencies that reach into the present. Even the early, still rather piecemeal, levee system’s capacity to alter the river’s sedimentation and the deltaic landscape of the mouths of the Mississippi was noted by the eighteenth-century observers. These levees were initially built to protect the city from annually recurring river floods, though they also protected the city from hurricane storm surges. Wind whipped flood waves usually pose a far higher threat to life and property in the low-lying Mississippi delta than the associated winds. The first levees to explicitly protect the city from hurricanes were only built in the aftermath of hurricane Betsy in 1965, the last “big” hurricane to flood New Orleans prior to 2005. This was the levee system that Katrina broke with its force and which caused the submergence of the city.

Though they have received much attention, New Orleans’s levees represent only one focus and one adaptive practice. Taking the form of a historical survey, the research begins with a critical reappraisal of the current benchmark definition of the concept of adaptation by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and reframes it in terms of adaptation as a relative concept. Adaptation varies according to time and space, and social and cultural stratification. The close study of these shifting relations make the concept a useful tool for historical research. Based on the premise that knowledge is a precondition for adaptation, this work retraces the history of “hurricane knowledge” and “science.” It then concentrates on five focus areas of adaptive practice: levee building, disaster migration, evacuation, disaster relief, and disaster insurance. As the narrative moves through time, it shifts focus between New Orleans, the Caribbean and Europe, and between French, Spanish and American Louisiana and the national U.S. level. Rather than assessing the “success” or “failure” of hurricane adaptation in New Orleans, the research considers the complex interplay of sociopolitical, economic, legal, and cultural factors in the development or stagnation of adaptive practices that have shaped the city to the present.