Arctic Change

This reflection on the North Pole and the question of ownership, presented during Anthropocene Campus 2014, is part of a series of exercises exploring the many literal and conceptual functions of borders and fences.

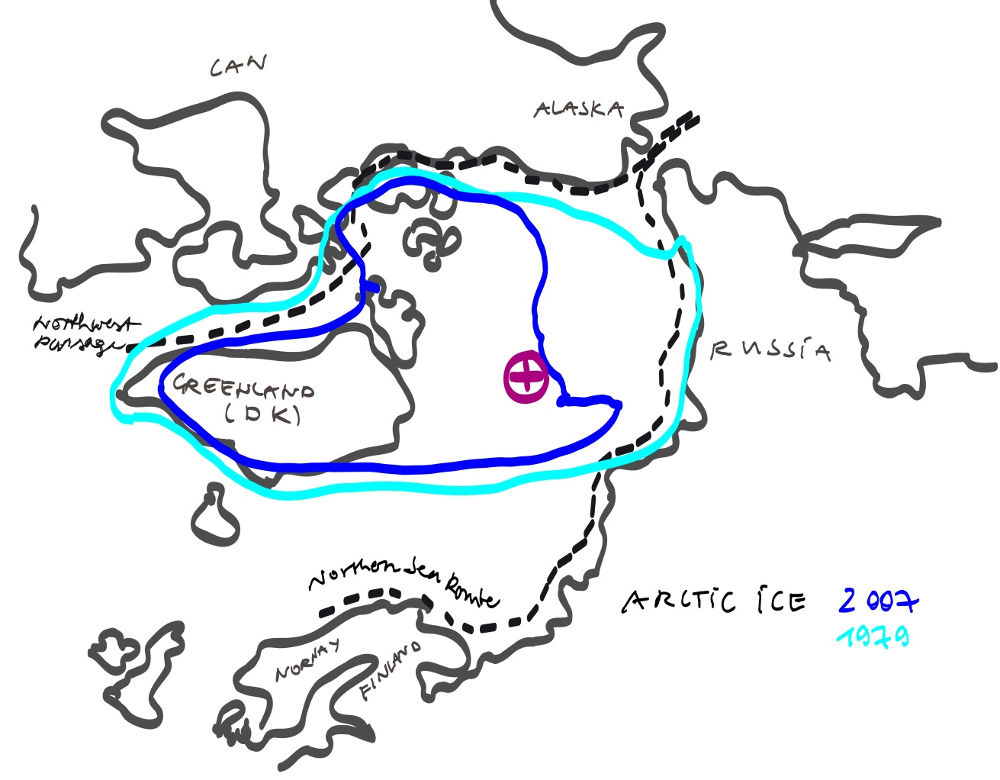

The North Pole is a mark on a map. Its inscribed existence represents no ownership. Yet, this spot in the North is a powerful tool in politics, economy, scientific exploration, and the war of the Anthropocene. In the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the North Pole and the surrounding Arctic ice are excluded from any national 200 nautical mile zone, known as an EEZ—exclusive economic zone. With climate change and the melting of Arctic ice, that status is questioned by five states with sea borders in the Arctic: Canada, Denmark (with Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Russia, Norway, and the United States (with Alaska). Each shifts its Arctic borders through remapping the continental shelf of the Arctic in order to expand territorial claims. The economic lures of new sea passages, as well as oil and gas resources, tempted the Kingdom of Denmark to go so far as to include the cartographic North Pole in its claim in December 2014 before the United Nations, with arguments based on histories of the past and visions of a sustainable North for human and nonhuman agencies.1 In 2007, a year of very significant sea ice melt, Russia stepped forward and exercised a military presence in the Arctic by planting a flag on the seafloor below the North Pole.2 A new Cold War is brewing in the North, as the ice melts and the oceans heat—day by day. The sea ice minimum in the summer of 2012 was much smaller even than the 2007 minimum. New records are accelerating.