An Archival Epoch?

Archiving in the Anthropocene

Focusing on the Formosa Plastics Global Archive, a digital repository documenting the global operations of the petrochemical industry, researchers Jason Ludwig and Tim Schütz demonstrate how archival production can be a catalyst for urgently needed action in the Anthropocene. They explore the potential of archival infrastructures for creating networks of solidarity around pressing environmental issues—contributing key questions, reflections, and speculative visions to this emerging conversation.

Since scientists Paul J. Crutzen and Eugene F. Stoermer first proposed the term,1 critical debates on the “Anthropocene” have raised potent questions about history, memory, and time: Who or what is responsible for the onset of our current geological age? To which date should we trace its beginnings? What should we even name this period so as to avoid universalizing matters of responsibility and response? Are we now rather inhabiting the Capitalocene, the Econocene, or the Plantationocene?2 Or is it instead the Technocene, the Manocene, or even the Anthropo*cene?3

Regardless of one’s “-cene” of choice, such claims about the causes, catalysts, and periodization of our epoch all attempt to orient present-day action and shape visions of desirable futures through excavating the historical processes that have resulted in global ecological disruption. This centrality of historical investigation to Anthropocene discourse has led historian Dipesh Chakrabarty to propose that current efforts to comprehend our planetary future require a new kind of thinking about the past, one that can connect the history of Earth and human systems. Vital to rethinking “Anthropocene time,” he argues, is not just a causal explanation for contemporary environmental woes but also a consideration of broader questions relating to how we must reorient our politics in accordance with nonhuman timescales, “so as to bring the geological into human modes of dwelling.”4

Such an epistemic shift entails reconceptualizing the infrastructures that underpin knowledge-making about the past. Recent literature in critical information and memory studies, for example, has sought to correct the general oversight of issues related to the archive in many discussions about history, memory, and the Anthropocene.5 Pointing to the centrality of archives and other knowledge infrastructures to the “process of collecting, interpreting, and redefining our current cultural moment,”6 these works have probed whether contemporary modes of archival production, curation, and maintenance are adequate for rethinking human and nonhuman histories and futures in the Anthropocene. An underlying anxiety about the status and agency of archives in the face of the challenges of the Anthropocene runs through these discussions. As archivist Samantha R. Winn notes: “If the demands of future memory work diverge from the competencies of archivists, it is incumbent upon archivists to adapt or die; memory work will continue regardless.”7

Rather than seek to provide a programmatic vision for archiving in the Anthropocene, we hope to contribute our own questions, reflections, and speculative visions to this emergent conversation. We first discuss information theorists and workers who have speculated about the “death” of archives in the Anthropocene and seek to imagine and create “living” archives suitable for addressing the epistemic challenges of contemporary environmental and political problems. We then add our own questions and concerns to the mix, arguing for the potential of archival infrastructures to produce anthropocenic publics and networks of solidarity around pressing environmental issues. To illustrate this vision, we focus on the case study of the Formosa Plastics Global Archive, a digital repository documenting the global operations of the petrochemical industry, which emphasizes how archival production can be a central tool to the formation of new political groupings and action in the Anthropocene.

For our purposes, we have adopted a broad understanding of what exactly constitutes an “archive,” including not only traditional institutions housing dust-covered books and written records stored away in boxes and stacked on shelves but also the various systems used to collect and distribute diverse signs, symbols, and data about the past, including public knowledge infrastructures and institutions of public history, such as museums, monuments, and digital repositories. Following anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillout, these systems are each implicated in the way in which our constitution “as subjects goes hand and hand with the continuous creation of the past.”8 One of the key challenges of archiving the Anthropocene, we argue, is remaining cognizant of—and operationalizing—the co-constitution of the historical record and our individual political subjectivities as we aim to produce knowledge about the past that can sustain more livable futures.

Living and dying archives

Recent literature in archival studies has examined how “the Anthropocene represents a progressive and possibly terminal illness for the contemporary discipline of archives.”9 Material decay, state abandonment, environmental disasters, and species annihilation all present existential threats to contemporary archives and to the professions that sustain them. Faced with the possibility that the archival discipline of the future will no longer resemble the current “conceptualization of archives as static spaces that preserve nostalgic records of the past,”10 information scholars and memory workers have sought to turn their grief over “the death of the archive” into a critical reflection on the role and responsibilities of archiving in anticipation of uncertain futures. As Winn argues:

By intentionally contemplating the “death” of archives as we know them, we create opportunities to evaluate the present dysfunction(s) of institutional archives, develop adaptation strategies to mediate the more immediate and violent consequences of climate change, and imagine what new practices might emerge from the fertile substrate we leave behind.11

If the Anthropocene tolls the death knell of traditional archives, then archival theorists must begin urging consideration of how alternative knowledge infrastructures might catalyze new cultural, political, and ecological formations. Through interrogating the assumptions and norms that structure traditional archival practice, such theorists have begun offering critical imaginaries of knowledge infrastructures that seek to put individual and collective memory to work in service of more liberatory futures.

The material conditions of historical preservation are one dimension through which scholars have sought to rethink the epistemological and ontological grounds of archival work. The increased risk of floods and fires due to climate changes poses particular challenges to archives, threatening the loss of unique and valuable records as well as damage to the buildings that house them. These concerns have resulted in efforts to “green” repositories and relocate collections away from geographically vulnerable areas.12 Some theorists have also pointed to the ways that the threat of archival annihilation offers unique opportunities to integrate a focus on nonhuman agency into traditional archival practices. This entails, for example, taking seriously actors such as mold and dust and the processes of decay and rot they catalyze. Archivist Dani Stuchel argues that conceptualizing these vegetal actors as enemies of preservation only reinforces extractive logics and shores up the binary opposition between humans and nature, mirroring the centering of a universalized anthropos in Anthropocene discourse.13 Such a perspective precludes critical consideration of how the historical record is itself a vibrant assemblage of human and nonhuman agencies. Stuchel argues that such forms of material decay are

a bodily change in an archive which triggers a loss of memory and identity for humans. Archival things are the transitional or memorial objects through which we mediate our grief about and connection to the past, but they are also entities of a certain kind, dying a certain kind of death within our perceptions.14

For Stuchel, dwelling on—or even curating—decay can itself be a way of working against the ontological borders separating the human and nonhuman, opening up new possibilities for memory work by urging a focus on the entire “life cycle” of preserved records and artifacts.

This appreciation of nonhuman agency and other alternative archival practices not only works against anthropocentric modes of being but can also catalyze new political formations. As traditional archives die and decay, and as we are ever further “forced to discuss the political regimes which built them in the first place, [and] the economic and social collapses which led to their current states,” archival theorists are seeking new values in which to ground practice and a new vision for archiving aligned with radical environmental and political transformation rather than with its traditional role as the “neutral, invisible, silent handmaide[n] of historical research.”15 Archives themselves thus serve as sites in which to imagine and exercise new ecological and democratic realities.

Theorists have introduced concepts such as the “ecological” or “living” archive to emphasize the alliance of archival practice to activist concerns. These visions of anthropocenic archives imagine repositories of collective memory that can serve as a “responsive, collaborative, and generative community space that counters existing systems of power and oppression.”16 Librarian Nora Almeida and archivist Jen Hoyer provide a compelling vision of what this can look like in practice with their description of the Interference Archive (IA) in Brooklyn, New York, a volunteer-run “archive from below” that collects ephemera from various social movements across the globe. IA emphasizes that its collection is both made-by-community and community-making. Its collection practice is guided by nonhierarchical collaborations between trained archivists and a host of volunteers with diverse backgrounds and skill sets, thus substituting community participation for the capital interests and professional norms that typically hold sway over the shaping of archival collections. The IA’s open-stacks policy also allows all visitors to browse its holdings and view materials at their own leisure. This ensures that the flyers, posters, and pamphlets in the holdings are preserved not only for their integration into the historical record but also to honor the intention of the social movements that created them by contributing to the free dissemination of knowledge aimed at catalyzing radical political action.

The IA illustrates many of the principles laid out in Almeida and Hoyer’s manifesto for living archives, which emphasizes that a collaborative and generative knowledge infrastructure “creates community and aspires to be a nexus between communities.”17 This vision of archiving highlights, above all, how community-curated archiving can be a potential antidote to the strain of political impotence found in many narratives of the Anthropocene, organizing collectivities and orienting community ideas and action in response to the diverse challenges of the Anthropocene.

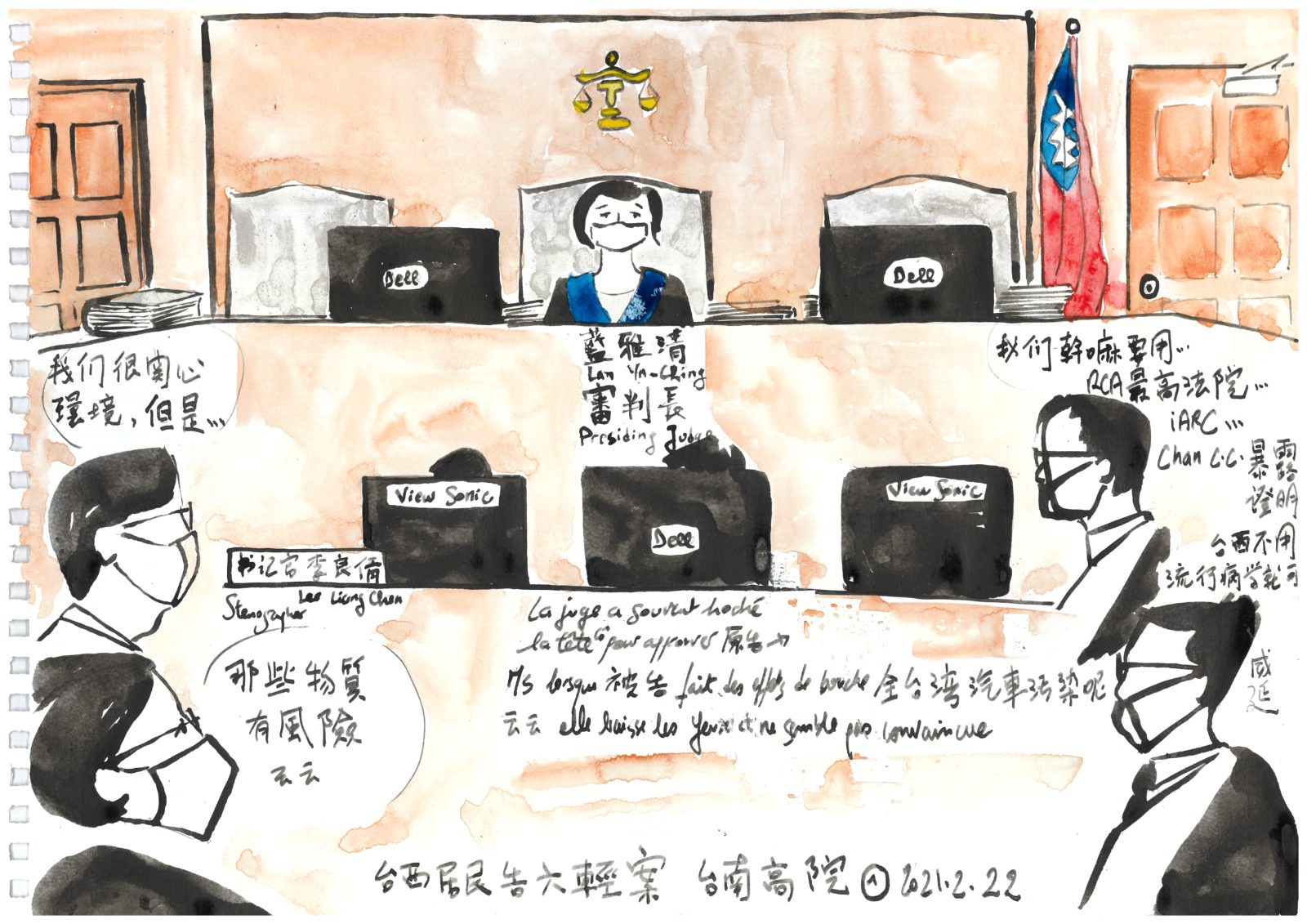

Yunlin Residents vs Formosa Plastics Group, Tainan High Court, February 23, 2021. This courtroom sketch by sociologist Paul Jobin is from an ongoing lawsuit by Yunlin County residents against the Formosa Plastics Group. The drawing is part of a series that captures the dynamics within the courtroom over the past five years. Archived as a form of “civic data”, it can be used to inspire litigation in other places. Sketch by Paul Jobin

Anthropocene archives and publics

Like the theorists and practitioners of the living archive, we share a concern with how community archives can help bring new political formations into being.18 If the living archive is attuned to the interests of local communities of practice, then our work is interested in how archival infrastructures can produce and support new (and often geographically dispersed) publics that coalesce around pressing environmental problems. In his 1927 book The Public and Its Problems, philosopher John Dewey argues that democracy depends on the formation of publics with shared concerns about social problems, but that powerful market and state forces often subdue the formation of these publics and, in turn, their criticisms.19

As more individuals and collectivities outside traditional archival institutions become involved in producing and preserving the signs, symbols, and data that document their past and present realities, archival infrastructures can be critical tools for prompting the formation of anthropocenic publics and supporting their epistemic practices.

Throughout our own collaborative ethnographic and historical research on community archives, we have identified a series of analytics to guide reflexive consideration of the design of community archival infrastructures.20 These tools of analysis seek to probe the archival genre, thus extending work in the “literary turn” in history and cultural anthropology.21 Exploring the specific injustices and exclusions to which particular archives respond draws attention to how archives are spaces where power is negotiated, contested, and ultimately consolidated. Archives are characterized as much by the materials they include as by those they do not as well as the injustices that such exclusions threaten to reproduce. Reflexive anthropocenic archiving involves attending to these imposed closures and silences while remaining mindful that the dynamic intersection of different systems and scales is characteristic of the Anthropocene. Archival genre is also expressed in the forms of data and participation that archives are designed to support. By situating human history within the broader ambit of geological deep time, the Anthropocene invokes diverse forms of historical data, integrating different fields of research and practice in the joint task of historical narration. Oral history, geological records, hydrological observation, and more—these diverse and complex forms of data are all implicated in the larger conversation around the causes and consequences of contemporary planetary dynamics, as well as in considerations of designing more livable futures. Archival design must take into account the requirements for collecting and circulating such diverse material, highlighting the crucial role of infrastructure. While the digital revolution has caused a veritable avalanche of data, it has also introduced powerful digital systems able to mediate the collection and circulation of material across the globe. These systems could be integral to the formation of anthropocenic publics, encoding ideology and producing meaning through their structures as well as their content. As a result, archival infrastructures constitute their users. This is why we see the technical design of digital archives as particularly generative and significant: such design sets up users in ways that are at least as powerful as the content they move through.

One example of an anthropocenic archive in which we see such dynamics at play is the Formosa Plastics Global Archive (台灣塑膠檔案館), co-developed by Tim Schütz and hosted by the Disaster-STS Network. The Disaster STS Network is an instance of the Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography (PECE), an open-source (Drupal-based) software to support virtual research environments for cultural anthropologists, historians, cultural heritage scholars, and other researchers working with diverse and often unstructured data. The Formosa Plastics Group is one of the largest petrochemical conglomerates in the world, with facilities in Taiwan, China, Vietnam, and the United States. Formosa has a record of explosions, routine pollution, and “mafia-like” behavior with environmental activists and other critics.22 In October 2019, Formosa agreed to pay a record settlement of $50 million for its release of plastic pellets into Lavaca Bay and Cox Creek in Texas.23 In Louisiana—in the petrochemical corridor known as Cancer Alley—environmental justice groups are challenging the opening of a new multibillion dollar Formosa Plastics complex.24 In Yunlin and Changhua Counties, following explosions and air pollution at a Formosa-owned naphtha cracking facility, Taiwanese citizens have pushed back against the expansion of the company.25 Furthermore, transnational Vietnamese advocacy groups are fighting for compensation following a 2016 marine disaster that resulted in a massive fish kill, caused by toxic spills from a Formosa-owned steel mill.26

The Formosa Plastics Global Archive grew out of a conversation with shrimp-boat captain Diane Wilson, lead plaintiff in the lawsuit against Formosa Plastics in Point Comfort, Texas. Watching and resisting Formosa since the early 1990s, Wilson has kept enough records to fill a large barn. Traveling by kayak, Wilson and others have also been tracking Formosa’s plastic pollution discharge to local waterways. Weekly water-monitoring reports produced by Wilson and collaborators include photographs and textual descriptions of plastic pellet pollution at water discharge outlets from the Formosa plant. Through ethnographic fieldwork in Taiwan, our research group learned that, like Wilson, local fishermen and other activists have likewise been collecting extensive documentation on Formosa’s activities, especially its air pollution and its detrimental consequences on oyster farming.

Over the last year, Schütz and the Design Team continued to build place-based archival collections for different Formosa-affected communities. Based on Wilson’s donation, the Formosa archive now includes leaked company audits, interviews with workers, meeting notes, and years of news clippings. On one hand, this work helps preserve the history of anti-Formosa activism as well as environmental movements more broadly.27 However, we also engage in creative curation of the material, letting new meaning emerge. For example, through an annotated interactive timeline of news articles, legal anthropologist Shan-Ya Su recounts how Yunlin residents—framed in the dominant narrative as “backwards” and susceptible to industry influence—did in fact express suspicion and resistance against the Sixth Naphtha Cracking Plant.

The format of the Formosa Plastics Global Archive also leverages the platform’s emphasis on collaborative analysis. Through a set of shared research questions, individual artifacts (photos, videos, text) or curated collections (called “essays”) can be “annotated” by users. One set of questions helps characterize what stakeholder groups have done to address environmental injustices, while another set draws out the many social and technical layers that constitute civic archiving capacity in Formosa-affected communities. Since some of the material has been used in recent lawsuits, annotation and publication of the data need to be strategic; to manage this, we use the platform’s capacity to preserve and work with data in digital spaces to restrict access to a delimited group until ready for release. We believe such analysis can help both scholars and the public better understand advocacy efforts in the present, such as through inspiring legal action across affected sites. For example, while the settlement in Texas has led to investments in citizen monitoring of the Formosa plant based on the Clean Water Act,28 such legislation does not yet exist in Taiwan, despite routine plastic pollution from the No. 6 Naphtha Cracking Plant.

Illustration by Kora Fortun for the digital exhibition Sugar Plantations, Chemical Plants, COVID-19. Stops include the Whitney Plantation (focused on the lives and perspectives of enslaved people in Louisiana), the Fee-Fo-Lay Cafe (where community knowledge is shared and the region’s storytelling traditions are preserved), and places where community members are organizing resistance to the building of yet another petrochemical facility in the area, on a former plantation site. Illustration by Kora Fortun (2020)

Another use for the archive is as infrastructure to build connections between the affected sites, pulling local problems into global visibility. Building on critically acclaimed projects like the 2013 exhibition When the South Wind Blows at the National Museum of Natural Science in Taichung,29 our research team staged a public event in Taipei involving printed documents, do-it-yourself displays of plastic pellets, and framed courtroom sketches. The sketches, drawn by Paul Jobin, document a case in Taiwan started by residents living next to the Sixth Naphtha Cracker.30 They powerfully recall both the dynamics of the legal case and are an inspiring example of collaboration between academic researchers and a “fenceline community” impacted by pollution.

Sugar Plantations, Chemical Plants, Covid-19 is another (virtual) exhibit and tour we developed, in this case with curators at the Whitney Plantation in Wallace, Louisiana, a museum built on a site formerly owned by Formosa.31 The tour is designed to mimic physical-world walking tours, inspired especially by the “toxic tours” run by environmental activists in many settings in this region. Rendered virtual, the tour collects diverse representations of Cancer Alley (put together over many years) that are especially powerful when considered in tandem, helping people zoom further into the deep history and complex landscape of the area. The tour further makes use of many functions and genres of the PECE software, especially the shadow-box-like PECE essay. The presentation encourages visitors to increasingly zoom out, moving from the proposed site of the new Formosa Plastics plant to the company’s global reach.

Anthropocene archives for just futures

Knowledge production in the Anthropocene must work to effectively link people working at different scales, in different sites, and with many different types of expertise. A place also needs to be created to house the diverse materials described here—visualizations and data that may seem to lack generalizable importance but are critical at the local level. At the same time, archives need to have global reach. In the case of Formosa Plastics, Cancer Alley is not far from Point Comfort (both are on the US Gulf Coast, about 500 miles apart), but forging connections between the two affected sites is still difficult. Further, activists in the US are working to maintain close relations with advocates and potential allies in Taiwan.

Archiving in and for the Anthropocene should be designed to help with the formation of interested publics and solidarity networks such as the one built around Formosa, and our analysis of what and how anthropocenic archives should operate must be both locally tuned and global in scope. Some of the archiving work will take place in data infrastructure design and through the creation of indexes and standard vocabularies that will make diverse data discoverable and accessible. One such way forward lies in the idea of the “just transition,” first articulated by US labor movements in the 1970s and resurfacing again in the context of “green” economies.32 Mindful of the contradictions that such grand shifts—for example, to renewable energy—entail, scholars argue that just transitions are needed across many domains, from environmental racism and food security to housing and automation.33 We argue for the significance of archives and public knowledge infrastructure in helping to facilitate such transitions, much like the productively “imprecise and insufficient” concept of the Anthropocene itself.34