A Conceptual Glossary

Interrogating the Question of “Whose?” and its Implications

The following is the beginning of a conceptual glossary developed by the working group “On Being Human or Not” for the seminar Whose? Reading the Anthropocene and the Technosphere from Africa, which took place during Anthropocene Campus 2016. It takes as its starting point the issue of silenced pasts and overlooked narratives, particularly as they pertain to the colonial era, and the persistence of this silencing (and its attendant power relations) in the present—in our so-called postcolonial times.

Introduction

The terms we chose emerged from a conversation with a conservationist working on the Schädel-Sammlung (Skulls collection) at the Museum of Prehistory and Early History in Berlin, and a tour of the Afrikanisches Viertel, or African Quarter, in the neighborhood of Wedding, led by Mnyaka Mboro, a member of the organization Berlin Postkolonial. The terms are: (Re)Naming, Provenance, Vandalism, (De)Humanization, Permanent Colony, Postcolonial Progressiveness, Unacceptable (contra-Illegal), Collection, Creative Resilience, Single Story, Exhibition, The State, and Neutrality.

The idea to create a glossary grew out of the desire we all had to subvert singular, hegemonic, Western-centric frameworks by accounting for a plurality of situated perspectives and experiences instead. We imagined this glossary to be open-ended such that each term would be interrogated from various angles; would provoke more questions than answers; would yield connotations and consequences of meaning in excess to the readily apparent; and would be applied to unexpected contexts in ways that could extend its significations beyond those predetermined and circumscribed by power. Some terms, like vandalism, are well established and widely used but undergo a contortion in form in our treatment. Others, like postcolonial progressiveness, are more specialized and/or attributable to our interlocutors, and are mined for their particular efficacy in accessing complex situations and tense relations. As becomes evident in our definitions, questions of whose and about whom are just as significant as those focused on what. Our emphasis on whose resonates with Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s dictum that “the production of historical narratives involves the uneven contribution of competing groups and individuals who have unequal access to the means for such production.”1

A selection from our terms is fleshed out below with musings, questions, anecdotes and images drawn from our encounters in Berlin, and specifically with unrecognized remnants of Germany’s colonial history in the city’s physical and social landscapes. We invite readers to add to our developed entries their own experiences, thoughts, and images, to initiate entries on proposed terms left unexplored, and to suggest and expand on terms of their own. In this way, we hope that our glossary-in-progress will become a collaborative discussion forum that amplifies viewpoints on the past and present which continue to be unheard.

(Re)Naming

To name is to “give a name to,” where a name is “a word or set of words, by which a person, animal, place, or thing is known or referred to.”2 But what does the standard definition or a cursory understanding of naming say about its inherent power dynamics? Who has the power to name and how does this circumscribe a name’s meaning? Is naming always revelatory? Or can it also serve to hide or elide? What does the act of rejecting a name or a demand for renaming entail? Attention to contestations around names can shed light on some of these questions.

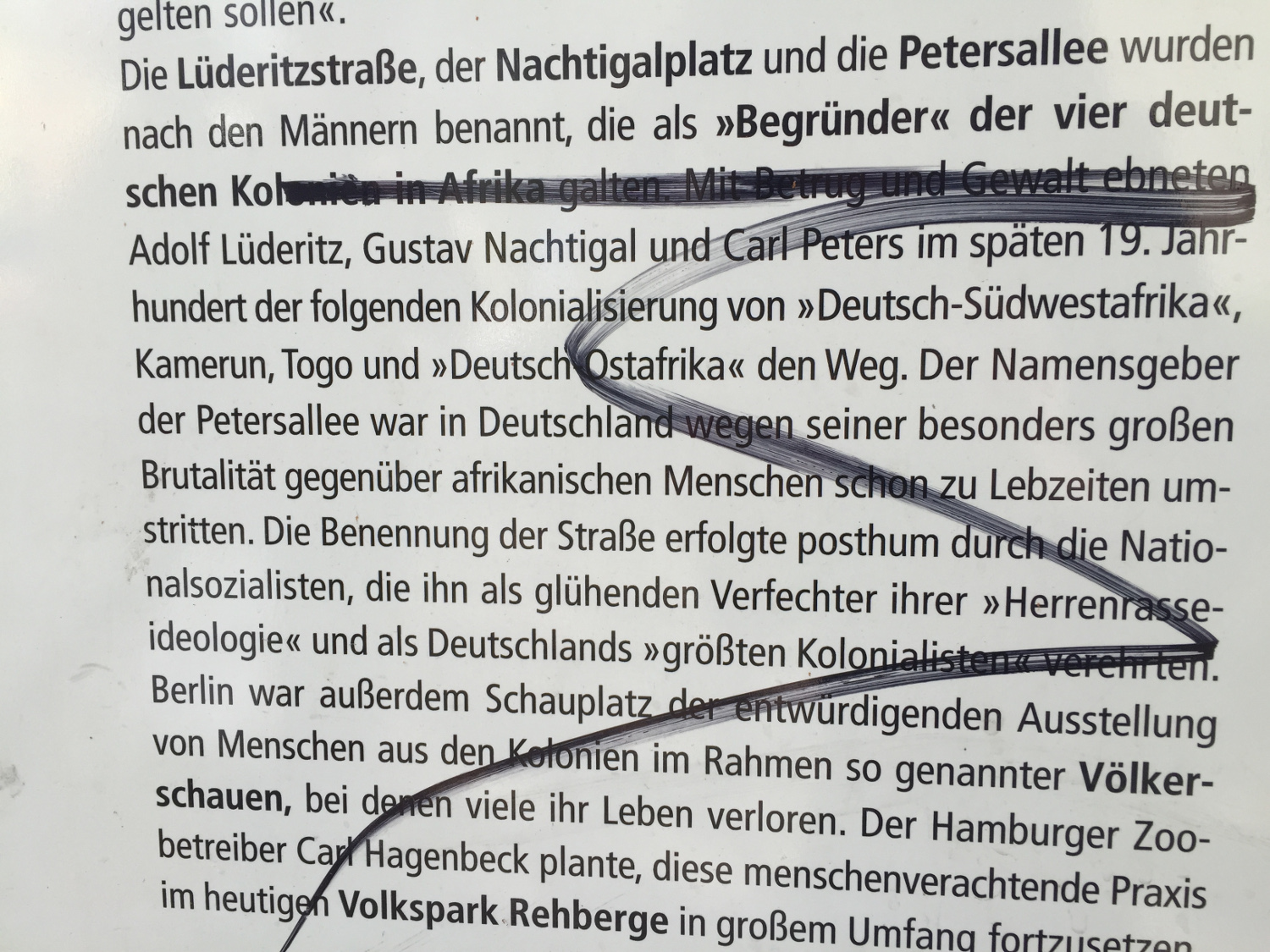

The African Quarter in Wedding was established in the late nineteenth century, conceived as a way of exhibiting German colonial power. Germany’s African colonies included, but were not limited to, German East Africa (present-day Burundi, Rwanda, and parts of Tanzania (1891‒1919)), German Southwest Africa (present-day Namibia and parts of Botswana (1884‒1915)), and German West Africa (present-day Cameroon and Togo (1884‒1919)). The neighborhood was and is still known today as the African Quarter because its streets are named after countries, cities, towns, and locales in Africa colonized by Germany (twenty-five streets) as well as German colony founders and colonial officials (three streets). The quarter came into existence with the naming of Kameruner Straße and Togostraße in 1899 and was developed under Kaiser Willem II, during the Weimar Republic, and later by the Nazis. Swakopmunder Straße, for instance, is named after Swakopmund, a major German colonial town in Namibia and the site of a concentration camp in which 2,000 Herero people died. Nachtigal Platz owes its name to Gustav Nachtigal, who was the German Commissioner for West Africa and responsible for the establishment of Togoland and Cameroon as German colonies.

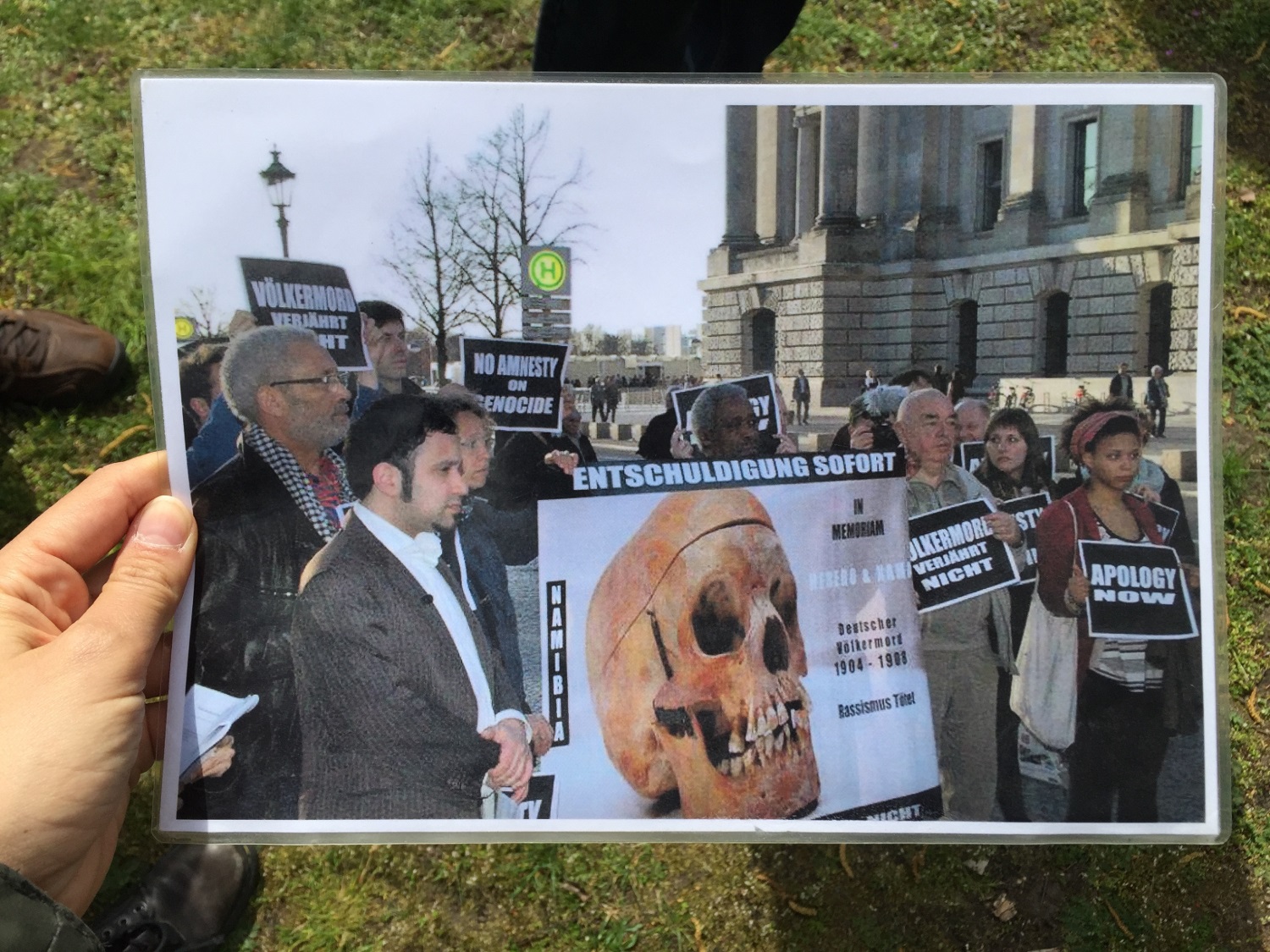

Activists, organizations like Berlin Postkolonial, and the local African community vocally condemn the persistence of colonially significant street names. They read it as an enduring, uncritical display of the German empire and its legacy; they argue that their persistence elides the empire’s bloodiness and reflects, as well as further encourages, its conceptualization in public discourse as geographically and temporally limited and by extension less injurious than other imperial projects. Berlin Postkolonial has been lobbying officials to rename two streets and a square in the African Quarter held to be particularly offensive—Lüderitzstraße, Petersallee, and Nachtigal Platz. It also regularly organizes tours that explain the significance of the quarter’s street names through orally conveyed historical narratives illustrated with archival materials, which include photographic prints, newspaper cuttings, and postcards.

During our tour, it became evident that the narratives and archival material from which Mboro drew were largely absent in public consciousness—even, at times, our own—and minimally acknowledged in the quarter itself (see the entry on “Vandalism” for further information on its acknowledgment). This near-absence raised questions about the expunging role played by the act of naming itself, versus that played by the lack of contextualizing knowledge, and about how the two relate to and work with each other. Is the name the problem here, or the want of tools for understanding its meaning from another (unofficially sanctioned) perspective? Might the problem best be formulated as how the absence of tools for understanding facilitates the continued unreflexive use of problematic names? Does a change in name automatically mean a change in tools for understanding? Does a change in tools for understanding necessarily lead to or require a change in name? There is a danger of erasure of another and more total kind, after all, entailed in renaming without retooling understanding—that of forgetting. Were the tools for understanding the brutality of German imperialism present, the African Quarter’s street names might be read less as an insulting celebratory gesture than as a respectful solemn reminder of wrongs.

Finally, the case of Petersallee allowed us to rethink naming and demands for renaming beyond the dichotomies of victory and loss or injustice and correction. Petersallee was named in 1939 by the Nazis after Carl Peters, founder of the German East Africa colony. Known as “bloody hand,” Peters was so brutal that he was recalled from Africa and removed from his post in the German civil service. There were demands to rename the street in 1984, on the hundredth-year anniversary of the Berlin Congress, but they proved unsuccessful. Instead, the Berlin Senate decided to rededicate the street in 1986, adding a smaller sign with the name of Prof. Dr. Hans Peters above Petersallee. Hans Peters was a lawyer and mayor who actively opposed the Nazi persecution of Jews. Is renaming, then, always an indication of change? Are there different degrees of renaming—for instance, in total replacement or mere supplementation or qualification? Do these degrees of renaming correspond to degrees of acknowledging the unacknowledged or rewriting the written? Might new names in lieu of the contentious sometimes serve as pacificatory tools, as is arguably the case with the addition of Prof. Dr. Hans Peters’ name on Petersallee? Is such a concession a way of continuing the old in new ways even more perilous, because of their guise of political correctness?

Provenance

Courtesy of Clapperton C. Mavhunga

Provenance is “the place of origin or earliest known history of something” or “a record of ownership of a work of art or an antique, used as a guide to authenticity.”3 Provenance is a central aspect in museum collections’ research and management that is not always without its accompanying legal and ethical quandaries.

The Museum of Prehistory and Early History in Berlin holds a collection of approximately 8,000 anthropological-osteological artifacts donated by the Berlin Museum of Medical History at the Charité in 2012. The bulk of these artifacts (approximately 5,600 skulls) are the surviving remnants of a collection developed by Felix Ritter von Luschan (1854‒1924) between 1885 and 1924. An Austrian doctor, anthropologist, archaeologist, and explorer, von Luschan was first Assistant to the Director then Director of the Africa and Oceania Department at the Ethnological Museum, before becoming a Professor at the Charité School of Medicine. He is credited with having introduced the methods of physical anthropology into German prisoner of war camps and with creating the von Luschan skin color classificatory scale.

Significantly, 83 percent of the museum’s total skull holdings are known to have been retrieved from Africa, and largely during the period of German colonialism. A number of these skulls were suspected of having been taken during the Herero Wars as well as from the concentration camps of the 1904‒07 Herero and Namaqua genocide in current Namibia. As part of the Charité Human Remains Project (2010‒14), forty-one skulls were identified as originating from the Walvis Bay and Luderitz concentration camps and were repatriated.

However, the origins of most of the skulls remain unknown. During the Second World War, the index cards and inventory accompanying the von Luschan collection of skulls were destroyed in the bombing of Berlin. This destruction has posed serious challenges for both repatriation initiatives and potential research around the collections. Minimal information remains in the form of inscriptions made directly onto the skulls themselves, which, when (rarely) complete, offer the collection locale and date, as well as the name of the collector. At present, all research using the collection has been halted and the museum’s efforts are concentrated, as the conservationist informed us, on determining the skulls’ provenance.

What does it mean when we speak of the “provenance” of human remains in museum collections or when we refer to them as “artifacts”? What historical conditions and political work does such unquestioned artifaction disavow? From whom do the specific skulls or “artifacts” in the von Luschan collection come? More generally, whose remains lie in museums accessible to observation and handling and whose lie shielded from view and from touch? What does it mean for museums to continue to hold onto, but not display, human osteological collections? Is manipulation for display of a different order of indignity than manipulation for scientific research? Why are some remains considered “non-renewable archaeological resources,” material for bioarchaeological research, or museum or national property, and others not?4 What unique forms do “provenance” research, notation, and management take when it comes to human bones? What are the legal and ethical quandaries specific to managing human osteological holdings? Whose responsibility is it to return collected human remains and to whom must they be returned? How does one deal with repatriation when the origins are unknown?

Vandalism

African community side of information board in the African Quarter | Vandalism Courtesy of Clapperton C. Mavhunga Mention of German colonies in Africa blackened out | Vandalism Courtesy of Clapperton C. Mavhunga

Vandalism is defined as an “action involving deliberate destruction of or damage to public or private property,”5 where destruction and damage connote ruin, especially of a physical nature, and where the idea of property is taken as inherent and unproblematic.

In a corner of the African Quarter sits the only neighborhood artifact that sheds light on the significance of the area’s street names. The artifact is a two-sided information board that presents a brief history of German colonialism and the quarter’s historical development. The board was installed by the Berlin City Council in response to demands made by activists. Following requests for edits to the text, which was initially prepared by city officials, it was decided that the board would present two versions, one on each side. One version would present the text of the City Council and the other that of the African community in Berlin. The African community side has since been vandalized, with references to “German colonies” in Africa blacked out.

The above is an example of vandalism in its most delimited and established sense: the “defacement” of public property in this instance, in a ubiquitous urban form (inscription), by individuals who are subject to punishment by the state. But what if we were to expand that definition to include other forms less often associated with the word and inflicted by other types of actors?

Take, for instance, the notion of “structural vandalism,” which we devised to describe the Nazi regime’s strategic placement of “typically” German pitch-roofed buildings to obscure from view interwar flat-roofed modernist structures in the African Quarter. Or “bureaucratic vandalism,” which we felt was apt for describing institutionalized damage enabled by individuals who evade responsibility for their actions by blindly adhering to policy, and evoking their adherence to it. Or “originary vandalism,” which we contrived to characterize as a particularly potent act of inscription, specifically notations made directly onto the human body and its remains, like those written on the surfaces of skulls in the von Luschan collection. Originary, here, evokes, in its most literal and direct sense, the branding of source or origin information onto the bones collected. More figuratively and indirectly, however, it also conjures the skull-writing act’s opening up into questions of “provenance,” the establishing of ancestry for repatriation, and the sociocultural construction of the sanctity of human remains by way of creation myths (in their myriad forms).

That these three examples, as well as others, remain unrecognized as vandalism points to how that which constitutes vandalism is inherently tied to context, which includes asking who is doing the vandalizing. Can the state be charged with vandalism, we asked? Moreover, the seriousness of a vandalism offense also relates to asking against whom it was targeted. Are there accepted forms of vandalism and unaccepted ones, and what determines which acts are classified as what? Does the established definition of vandalism allow for what might be called de-vandalism (or the removal of vandalism marks)? Is de-vandalism in actuality no more than another instance of vandalism?

If naming is synonymous with writing and rewriting, then vandalism, we mused, might be analogous to editing. For vandalism, as it became increasingly clear through our consideration of various examples, is a process of layering in which vandalized layers do not wholly disappear; the layers remain as a testament to the times and sentiments. Vandalism, thought of as such, might be productively recuperated to constitute material for more inclusive public discussion and debate. In our definition of vandalism, might de-vandalism, with its excisory impulse, be of a wholly different category than the vandalizing act?

(De)Humanization

To dehumanize is “to deprive of positive human qualities” (emphasis mine) whereas to humanize is “to make (something) more humane and civilized,” or to “give (something) a human character.” In short, to dehumanize is to strip humans of their humanness and, conversely, to humanize is to bestow onto nonhumans human qualities. But what does it mean to be human? Human is defined as “relating to or characteristic of humankind”; as “of or characteristic of people as opposed to God or animals or machines”; as “showing the better qualities of humankind, such as kindness”; and, in the field of zoology, as “of or belonging to the genus Homo.”6

Contra the “neat” definitions given above, which rest on assumptions of universal agreement on categories like “humankind” and “Homo” and of who they include/exclude, characterizations of the human have been formulated and reformulated throughout time. As Dominic Pettman writes, drawing on Giorgio Agamben, “Homo sapiens is ‘neither a clearly defined species nor a substance; it is, rather, a machine or device for producing the recognition of the human.’”7 Significant scholarship since Aristotle has been dedicated to shaping this “anthropological machine,” to delineating distinctions between humans and animals, and establishing human exceptionality based on qualities like rationality and participation in politics.

These distinctions, and their perceived lack in certain groups, were used (and continue to be used) to equate group members to animals, to cognitively less-developed humans (i.e. children), and to the evolutionary predecessors of modern-day Homo sapiens (i.e. Homo erectus). These distinctions in turn are drawn upon to justify inhumane treatment. The latter equivalence in particular is significant to the case of Africa, in that human evolution stories are commonly conceived “as linear teleological narratives of progress from bestial African prehistory to a civilized, European present.”8 The scientificization of these distinctions and narratives involved a trade in skulls, for evidentiary material in fields such as anthropometry (i.e. measuring and comparing cranial capacity) and paleoanthropology.

Dehumanization is most commonly associated with the direct treatment of individuals or groups, specifically their subjection to verbal or physical abuse and denying them what are perceived as inalienable human rights (though the meaning of these rights is historically contingent). Mboro informed us of the dehumanizing plans in the early twentieth century to convert the African Quarter into a zoo devoted to the display of animals and peoples from Africa. He also relayed horrifying tales of how African women in German colonial camps were forced to boil the skulls of dead prisoners (sometimes their relatives), scrape off any remaining skin and gouge out their eyes with glass shards, and package them in preparation for shipment to collections in European museums and universities like von Luschan’s.

One member of the group proposed that such forms as the two examples given above should be deemed instances of “spectacular dehumanization,” and that the term should be expanded to include forms of “slow dehumanization” and “structural dehumanization” as well. “Slow dehumanization” borrows from Robert Nixon’s notion of “slow violence,” which he defines as “a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.” It is a term used by Nixon to describe the violence of “slowly folding environmental catastrophes.”9 As Nixon also points out, slow violence is most often committed against those whom Kevin Bales calls “disposable people”—the colonized, the marginalized, the poor, and the stateless.10 Instances of “slow dehumanization” are pervasive in the stories of German African colonies, and likewise “structural dehumanization” in the urban planning of the African Quarter and in the maintenance of skull collections at institutions like the Museum of Prehistory and Early History.

Some questions that were raised by the group were: What does it mean to be human? Who is human? Human at whose expense and to the benefit of whom? Whose humanity? Does speaking of inhumanity always reify the category of humanity? Does humanity lose its efficacy as a term given the human capacity for inhumanity, and what does it mean to speak of inhumanity given its actuality as a human trait? Can we talk of humanizing or rehumanizing dehumanized subjects? Does such talk work to productively underscore the malleability of the category of the human? Does consciousness of this malleability affect the potential for further exclusions, either positively or negatively? Are we in need of new terms to supplant “human” and “humane” as descriptors of treatment, given recent efforts to deconstruct the human–animal duality and dismantle established species hierarchies? What might that new term be?

Permanent Colony

The term “permanent colony” is drawn from a stop along our route during the tour to the allotment garden colony Dauer-Kleingartenverein “Togo,” called Dauerkolonie Togo (Permanent Colony Togo) from 1939 until quite recently. Though derived from the name of a particular place, the term “permanent colony” is appropriated here to encompass the continuation of special concessions and dependencies between colonized and colonizer in the postcolonial era and, more importantly, the nostalgia for colonialism and the romantic image of the colonized held in the mind of the colonizer.

Dauer-Kleingartenverein “Togo” is one of many Gartenkolonien (garden colonies)—gated garden plots that lie in the shadow of Berlin’s multistory buildings and off the main thoroughfares. Beginning in the nineteenth century, these rustic-looking enclaves served as weekend and holiday escapes for the working classes from the hustle and bustle of the city.11 But as Maria Theresia Starzmann points out, the garden colonies were “also part of an imaginary geography that emerged out of a particular colonial discourse in Germany”;12 established largely after Germany had lost its colonies in 1919, their naming and association with German outposts in Africa meant that they served as “melancholic reminders of a powerful colonial past.”13

Moreover, these gardens were inhabited by those people who were largely excluded from the “colonial encounter abroad”—“the urban poor, who were unwanted as settlers in the colony and exploited as factory workers in the metropole.”14 Like the panorama paintings of the nineteenth century, the garden colonies of the twentieth speak of an unfulfillable “shared desire to travel to far-flung places” and of consequent attempts to bring the foreign home (inevitably entailing a process of domestication).15 The garden’s rustic European layout, design, and architecture obscure the connections between this, the built form, and global power networks, much like the African Quarter’s leafy residential plots do for its street names.

Postcolonial Progressiveness

Courtesy of Clapperton C. Mavhunga

“Postcolonial progressiveness” was a term used by Mboro in relation to the story of naming Ghana Straße, and which, similar to the permanent colony, we adopt more broadly. Ghana Straße was named in 1958, one year after the country gained its independence. Although a British colony, Ghana had effectively been part of the German colonial sphere in the eighteenth century. Mboro’s term indicates a specific facet of the “permanent colony” conundrum—the irony of the progressiveness touted by previously colonized nations in the “era of decolonization” and its aftermath. It refers, specifically, to colonizers’ claims to be postcolonial and to support the liberation of the colonized, yet to continue with their continued practice of colonialism in new forms (neocolonialism).