Anomalous Alliances

Nature and Politics in the Yasuní Proposal

Techno-scientific practices of material classification are key to resource extraction: from the sampling of soils in the search for precious minerals to the sampling of microorganisms for medical purposes, material classification allows the conversion of every minute aspect of the Earth into a potential resource. In particular, geology and biology have provided the main tools through which the Earth is axiomatized, allowing it to enter multiple regimes of economic and financial calculation. Even if the classification of nature according to scientific frameworks is not necessarily related to the practice of resource extraction, it carries within itself a propensity for instrumentalization (numbering, classifying). In any case, the problem is not science per se, but the fact that its “eliminativist” mobilization—to paraphrase Stengers—has come to constitute “common sense” for how nature is to be understood. Thus, today, we are facing the important question: Is it possible to decolonize techno-scientific practices? The well-known case of Yasuní-ITT in Ecuador provides, in my view, a unique perspective from which we can start to discuss these problems.

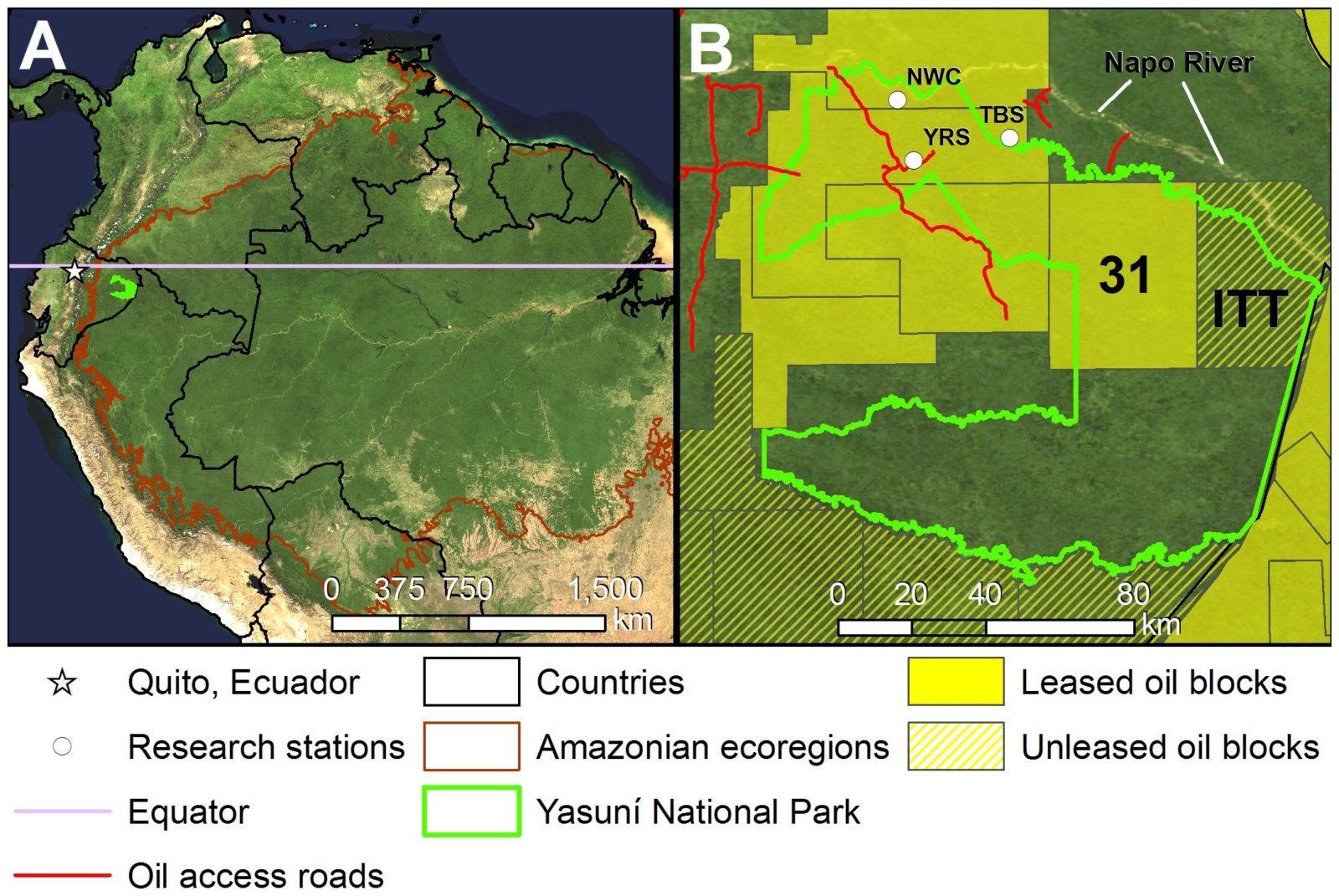

A) Location of Yasuní National Park at the crossroads of the Amazon, Andes and the Equator. B) Oil blocks and oil access roads within and surrounding the park, NWC = Napo Wildlife Center, TBS = Tiputini Biodiversity Station, YRS = Yasuní Research Station Map by Bass MS, Finer M, Jenkins CN, Kreft H, Cisneros-Heredia DF, McCracken SF, et al. (2010) Global Conservation Significance of Ecuador's Yasuní National Park. PLoS ONE 5(1): e8767.

In 2007 before the General Assembly of the United Nations, the Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa declared his country’s commitment to avoid exploration of the extensive oil reserves in the Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (ITT) oil fields in the Yasuní National Park. Located in the Ecuadorian Amazon, Yasuní-ITT has oil-in-place amounting to 846 million barrels, which is equivalent to 20 percent of the nation’s overall oil reserves. This groundbreaking initiative proposed that Ecuador would refrain from exploration of ITT oil reserves, in exchange for receiving 50 percent of its proven value from the international community, in particular from the developed countries.1 This would be equivalent to 3.6 billion dollars over thirteen years. At the core of this project there were three main objectives: 1) to protect indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation; 2) to conserve the unique biodiversity of the Yasuní National Park; and 3) to avoid CO2 emissions as a result of the extraction of hydrocarbon resources. This last point was particularly important, as the expected value of CO2 emissions prevented would amount to 407 million tons. If taking into account all the environmental effects of processes associated with oil extraction such as deforestation, logging, or the setting up of infrastructure, the real value would be even greater. It should be understood that Ecuador is a country where at the time of the proposal in 2006, 49 percent of the population lived below the poverty line, and where oil provided 22 percent of GDP and 63 percent of exports.2 Because of this, the direct relation between oil and development should be made, particularly with the Correa government’s investments in infrastructure, health care, education, and housing. According to Carlos Larrea, who was one of the main proponents of the Yasuní project, the proposed fund would be managed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Interest earned by the fund would be invested in “social development, nature conservation and implementing the use of renewable energy sources, as part of a strategy aimed at consolidating a new model of sustainable human development in the country.”3 In this way, the Yasuní-ITT initiative brought together for the first time the asymmetries of colonial history and global development as well as the debates around indigenous rights, climate change, and the protection of nature.

Underground Frontier

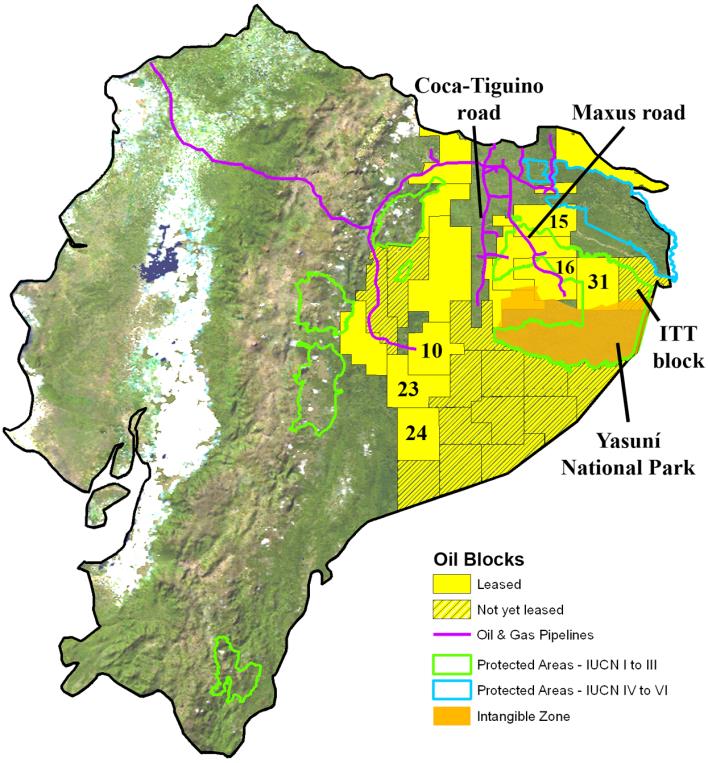

And yet, it is perhaps no surprise to note how the techno-scientific practices of material classification that characterized colonial forms of survey remained central to the entire process. The first step and the most evident took place with regard to the procedures for the prospection of underground natural resources, namely oil and natural gas. Research into Yasuní National Park has been ongoing since Shell Oil started operating in Waorani territory in the 1940s, and to this day, it has been conducted both by transnational companies and by the Ecuadorian state. From such research, there has emerged precise quantifications of oil-in-place, locating Yasuní’s near-850 million barrels of proven reserves of heavy oil (14.7º API) on a global map of emergent crude investments. Further surveying was expected to provide the project even more detail: “Even though the proven reserves in the ITT field total 944 million barrels, there may be additional reserves up to 1.53 billion barrels, the value of which cannot yet be ascertained as the 3D seismic prospecting has not been performed.” Elsewhere I have described this as the underground frontier, whereby the underground becomes a site of paranoid deployments of techno-science towards ever more precise forms of mapping and visualization.4 But if the real dimension of these processes is only visible later—in a multitude of forms such as pollution, contamination or dispossession—the fact that disputes over the future of Ecuador’s Amazonian plains is taking place according to a map of oil blocs is a powerful reminder of the processes at play in the nation’s territorial politics.

Sumak Kawsay

Techno-scientific processes of material classification enter into conflict with the modes of knowledge production of the populations currently inhabiting the Ecuadorian Amazon. The majority of Ecuador’s oil-concession blocs overlap the territories of the lowland areas of Kichwa, Shuar, Achuar, Shiwiar, Cofán, Siona, Secoya, Zápara, and Waorani. Epistemic differences are even more dramatic if we consider local peoples inhabiting the Yasuní National Park: home to about 3,000 contacted indigenous peoples who belong to the Waorani and Kichua (Quechua) ethnic groups, it includes two tribes in voluntary isolation as well; the Tagaeri and Taromenane, whose cultural practices are based on gathering, hunting, and semi-nomadic agriculture. I will not extend into an analysis of indigenous epistemologies except to say that concepts of property and territory are inapplicable to local practices of living; and also that the distinction between surface and subsoil (essential to oil extraction) makes no sense whatsoever to a conception of nature as an unbounded and living entity.5 Paradoxically, the gridding of Amazonian territory exists in the context of a nation with some of the most progressive politics in the world towards indigenous peoples. In 2008 Ecuador was the first country to introduce the rights of nature into its constitution: Article 275 indicates that the nation’s development should take place with respect for the idea of “Sumak Kawsay” or “El Buen Vivir,” that is, to respect the rights of peoples, communities, and nature. This move is one that reflects the growing awareness of the dramatic humanitarian consequences of nature’s destruction. Furthermore, in fact, it carries direct implications for several legal cases—most notably the class-action suit Aguinda v. ChevronTexaco.6 However, we would be mistaken to conceive the rights of nature simply as the protection of nature as it is conceived in Western culture. On the contrary, what is at stake is precisely the possibility of other conceptions and practices of nature, and thus, in fact, the problem of the rights of peoples, particularly indigenous peoples.7 Nonetheless, it is one thing to recognize indigenous epistemologies in principle, but quite another to recognize their epistemologies as the basis for political negotiations. Indigenous peoples have unique knowledge of medicinal plants, of the local environment, and of animal species inhabiting their regions. However, in no way have their forms of territoriality or their knowledge of the Earth influenced the Ecuadorian policies towards mapping and material classification.

Biodiversity

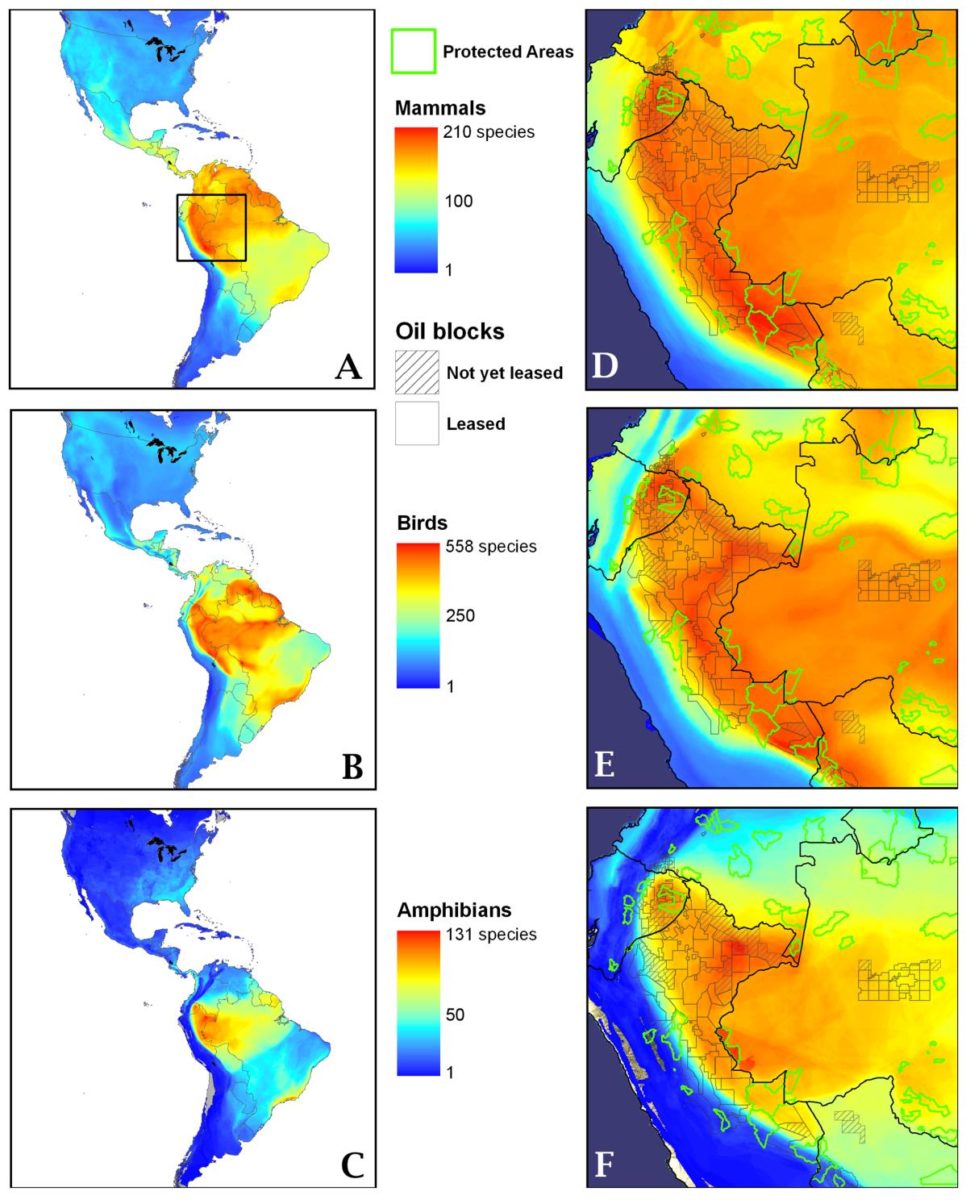

If the opposition between resource extraction and local communities is a common problem all around the world, what makes the Yasuní case unique is how another form of territorial classification came to shift the nature of the conflict. This is the classification of the environment according to its biodiversity, i.e. the amount of living animal and vegetal species in a certain area. Biodiversity is a concern whose importance for developed nations derives, paradoxically, from the environmental destruction promoted by developed nations themselves. Due to its high diversity of animal and vegetal species, in 1989, UNESCO declared Yasuní to be a Man and Biosphere Reserve. And this declaration was key to the Yasuní project in arguing for the need to keep the oil underground.8 According to Bass and her co-authors, the Yasuní landscape is “one of the two richest in the world for amphibian species, the second richest known to date for reptiles, within the top nine richest centers for vascular plants (and the top center for trees and shrubs), among the richest lowland areas for birds, high in mammal richness (particularly for bats), and very rich in fish species.” In the Yasuní National Park, there are approximately 4,000-plant species, 173 species of mammals, and 610 bird species.9 Furthermore, it has more than the total number of native tree species of the United States and Canada combined. And even by Amazonian standards it is unique: “Yasuní harbors roughly one-third of the Amazon Basin’s amphibian and reptile species, despite covering less than 0.15% of its total area.”10

Thus, we move from a classification of nature as a source of energy resources, to the classification of nature in terms of the amount of living species. In doing so, a discussion about rights, also becomes a discussion about a global heritage of knowledge that is essential to all sorts of present and future research agendas.

The calculation of politics

Managing different modes of knowledge production within a single and coherent strategy was central to the Yasuní project. Evidence of this is found in the frequent references in Larrea’s, Yasuní -ITT: An Initiative to Change History to the “Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change.”11 In doing so, Larrea’s proposal clearly shows it makes an effort at articulating indigenous, scientific, and environmental benefits together with economic ones. However, given that the purpose of the “Stern Review” was predominantly to promote climate change as a business opportunity, its referencing by Larrea in his proposal for Yasuní-ITT evidences the risks inherent in such complex negotiations.

One such risk resulted from the framing of nature as a commodity. If, initially, the proposal consisted of a moratorium on oil extraction, it still required some form of financial compensation against critics that claimed the project implied a loss of important revenues to the state of Ecuador. The idea that followed was that of selling Yasuní bonds at the price of oil; and finally, the government proposed the sale of Certificates of Guarantee Yasuní (CGY) at the price of non-emitted carbon. Thus, the radical idea of leaving oil underground was slowly converted into the environmental benefits of avoiding carbon emissions and the financial gains of entering the carbon-trading markets.12 As recognized by Alberto Acosta this focus on the problem of “compensation” was extremely risky in both political and financial terms: “such ‘compensation’ doesn’t necessarily guarantee nor is directly linked to the local communities, or with the environmental protection or recovery of previously degraded areas, or areas that lost the capacity to provide sustain to the populations.”13 A similar point is noted by Keller Easterling: “when the expensive and cumbersome technical apparatus of the carbon market is exploited and chiselled, what values of the spatial antecedent—the forest itself—will remain?”14

The mobilization of biodiversity was also not without its problems: to focus on the rights of nature from the perspective of biodiversity allows displacement to take place, from the defense of indigenous rights to difference to the protection of biological diversity. As indigenous communities begin to defend their modes and practices of living because they are “sustainable” and respectful to the world’s “natural patrimony,” it seems that they themselves are quickly becoming samples of a diversity of culture that needs to be maintained, in the same way that samples from soon-to-be-extinguished animal species are. From this perspective, the focus on biodiversity reflects the violence to which indigenous peoples are subjected, such that in order to survive they need to present themselves as an integral part of a diverse environment.15

However, perhaps the main point of contention was how the Yasuní project did not clearly oppose the government’s extractive policies: the danger of the project lay in the reinforcement of the epistemic mechanisms by which dispossession takes place, allowing the protection of one bloc to be used as a rhetorical device to justify the massive exploration of dozens of others. Even the site of dispute itself was defined by the boundaries of an oil bloc (ITT) and not by the jurisdiction of an indigenous territory or a natural park. And indeed, when the project was cancelled, the underground frontier kept expanding as if nothing had ever happened. Despite receiving pledges amounting to a total of 200 million dollars by 2012, on August 15, 2013, Ecuador’s president Rafael Correa scrapped the plan. “The world has failed us,” he said, before describing the world’s richest countries and greatest polluters as hypocrites that expect countries like Ecuador to sacrifice development for the environment.”16 The disparity between victories such as the enshrining of “Sumak Kawsay” in the Ecuadorian constitution, and the continued destruction and exploration for oil on sites that such clauses are supposed protect, makes evident that even if important constitutional rights are granted to indigenous communities, the foreseeable profits from oil extraction have an unequal power of attraction.

Anomalous Alliances

The Yasuní project from the start was riddled with difficulties. Yet, we know that the work of producing alternatives doesn’t take place in abstract ideal conditions. In a continent emerging from 500 years of colonization, whose economies have been developed as nature-exporting ones, to move away from oil is easier said than done; equally one cannot fail to recognize the important social developments that oil has brought to Ecuador since Correa’s tenure as president. In fact, the Yasuní issue came at a time when within Correa’s government were some of the most progressive thinkers and movements of the Ecuadorian left, for whom the question was never simply the opposition to resource extraction, but how to set-up a mechanism to move away from it.17

Because of this, I prefer to see in the Yasuní-ITT initiative a powerful example of setting up alliances between incommensurable practices of knowledge production. This has been evident in the way that indigenous rights, climate change, scientific research, and economic development were brought together around the same table. It is in this sense, that the Yasuní-ITT initiative is a powerful example of the mobilization of techno-science for the protection of something that escapes science itself, or in other words, a “counter hegemonic use of hegemonic instruments.” Furthermore, the initial strategy represented a break not only with local but also global expectations concerning what can be done with oil; to leave the oil underground suggested something almost unnatural, an unprecedented stoppage in the extractive motors of development. This break proved to be politically powerful, signaling a possible reorganization of horizons and expectations. But if entering the pragmatics of political and financial calculations was a necessary step, the final proposal of indexing non-extraction to carbon trading, represented a level of deterritorialization from which there was of no return. In such a differential relationship, there could be no Amazons anymore.

Despite its ultimate failure, the Yasuní-ITT is nonetheless a singular source of inspiration. It seems to me that the task of today is not only that of decolonizing techno-science from its eliminativist and imperialist tropes, but also to develop a much stronger project, whereby the perspectives from which we use tools of seeing, sensing, or measuring the world, are radically expanded. Tools such as these should not be used only to negotiate active disputes but actively to contest the problems that are up for discussion in the future. Could this happen by science being actively re-invented by indigenous knowledge? If so, what other forms of classification could one speak of, and what subjectivities would this open up? The result could only be a monstrosity like the Yasuní-ITT—a monster invented for a post-oil world that does not yet exist.